The only thing that these movies have in common is that there is a bad lieutenant. For a Cliff’s Note perspective of the two movies, I think that a quote from each director about the other summarizes it all.

Ferrara: “As far as remakes go, … I wish these people die in Hell. I hope they’re all in the same streetcar, and it blows up.”

Herzog: “I’ve never seen a film by him. I have no idea who he is….I would like to meet the man…..I have a feeling that if we met and talked, over a bottle of whiskey, I should add, I think we could straighten everything out.”

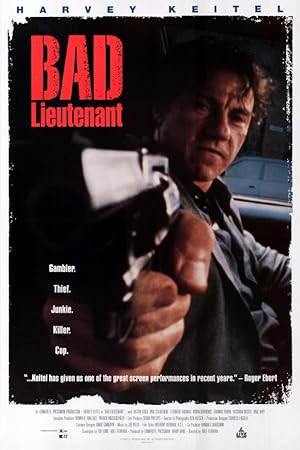

Ferrera’s movie came first. It takes place in NYC & the pivotal investigation is loosely based on real life events. It is not a fun movie to watch and is inescapably oppressive. I would not recommend it. It mainly focuses on the unnamed Bad Lieutenant, played by Harvey Keitel, as he basically careens haphazardly from moment to moment, barely doing anything remotely considered appropriate police work. His entire life is a self destructive binge of drugs, exploitation and gambling.

When he is initially introduced as a father taking his young children to school, the only time that he seems vaguely normal or sober, he soon has to heavily anesthesize himself from normalcy and never rises from the stupor. This man hates himself, his life and everything around him. The audience knows very little about him except that he has been fighting to survive on the streets since he was fourteen except it appears that he has lost that fight. None of his coworkers seem to notice his obvious decline or if they do, the blue wall of silence closes ranks and ignores it. This man does not have it together. Everything he touches turns to ash & instead of investigating crimes, he seems to be actively and clumsily conducting them.

When he is confronted with the pivotal investigation, a nun brutally raped by a couple of teens, a Catholic Church desecrated, and the nun’s peaceful & forgiving response to the attack, he tries to pretend that he isn’t affected and continues to be above it, but he is haunted by hallucinations of Jesus being crucified on the cross and questions his identity: how can he be so awful and a Catholic and wonders how he can change. This contemplation is not done in any elegant manner. If anything, he behaves worse until he literally has a “Come to Jesus” moment-cursing Him out, mournfully crying out & ultimately bowing at His feet.

Accidentally he solves the crime, but instead of killing the two rapists, he gives them some of his drug money while smoking a crack pipe with them, helps them to escape per the nun’s earlier comments that though she knew the perpetrators, she didn’t want revenge, but forgiveness. He resists the urge to kill them, which is what he would normally do in this situation. He is shot in his car outside the Port Authority because of his gambling debts soon thereafter.

Ultimately Ferrera’s vision of redemption is a spiritual one with very little material or objective reward. Keitel is naked literally & figuratively, revealing all the pain & torment of his character’s soul which is not wholly relieved even after he accepts that God could even forgive someone like him. One could even say that there is no redemption–just a drug addict’s hallucination–except that it does end with a miracle: the lieutenant solves the crime through no effort of his own & tries to do the right thing. Ferrera is rooted in gritty reality–you can come to Jesus, get forgiven & do one good thing, but in this world, you’re still going to get shot in the head soon after sucking on a crack pipe. Still the worse sinner gets redemption and probably benefitted from dying violently–he escapes before he can ruin what redemption he receives.

Herzog’s vision is the complete opposite. It IS fun to watch. Choosing New Orleans is no accident. It is a seat of institutional corruption as displayed by the government’s response to Hurricane Katrina’s impersonal destruction. Cage is ultimately the hero because even though he shares the same corruption of New Orleans, he does not share its disregard or disrespect for its citizens though his crime fighting, which is the focus of this film.

He is Quasimodo cop–his body as crooked as he is, but ultimately a New Orleans good ole’ boy cop who got addicted to drugs because of his good deeds, not because of nihilistic, incessant, self destructive impulses. Sure he gambles, but all his bad deeds seem to be part of the old law enforcement institution, not the vices of one bad apple. In a day of PC whistleblowers and outside attention, they have to appear to be good, but Cage’s cop persona is basically good in comparison to one guy who likes to beat up & kill suspects. If a woman wants to help her boyfriend escape from a drug charge by doing drugs with Cage and having sex with him, who is he to say no.

If Keitel is naked and bears his soul, Cage’s named character is not only clothed, but his uniform is a light brown suit, $55 underwear and a gun tucked in his waistband, NOT a holster. The camera lovingly condones and identifies with Cage as opposed to Ferrera’s camera, which maintained an almost documentary camera style distance from Keitel and briefly veered from following his every move. Where Keitel was a mess, even when Cage’s character recklessly does things–all in order to solve a slaying of an illegal immigrant drug dealer’s family, it is part of a grand plan. Cage is crazy like a fox and ultimately this story isn’t concerned with his soul, but his present life.

The point of this movie is Herzog’s admiration of an anti-hero and how a mad man solves ever escalating obstacles while juggling his roles as lieutenant, drug addict, gambler, boyfriend & son in that order. Whereas Ferrera’s film was a series of improvisation and destruction, Herzog’s film is actually quite conventional and disciplined despite surreal situations and Cage’s expressionistic and stylistic acting style. Cage’s character gets the bad guys, the girl, the money, the promotion, the drugs, but it still ends with a note of dissatisfaction.

This anti-hero is stuck in a never ending cycle of needing drugs because of the pain which resulted from a good deed. The only hope that he gets is to sit with a grateful man whom he saved surrounded by inscrutable creatures at the aquarium. If Keitel hallucinated Jesus, Cage hallucinated a pair of iguanas, break dancing souls that bear an odd resemblance to later tv footage of a matador gored by a bull and an alligator’s mate on the side of the road watching another alligator dying on the road after a car accident. Cage’s last line is about imagining whether fish dream. So Cage’s character is left wondering–despite his reptilian ability to survive, is he simply stuck in a never ending hunt, constantly swimming to stay alive like the sharks behind him, or will he find rest and finally have no pain?

Though Herzog’s film is more fun, Ferrera’s character wins on basis of realistic happy ending: the bad lieutenant finally gets to rest whereas Cage is still trapped and doomed to juggle a couple more balls, albeit successfully, of father and recovering addict in a never ending world of corruption and pain. His victory is superficial and he no longer has the solace of another person to take drugs with openly, but by the end of the movie, must maintain a facade of sobriety. Will he ever get an interior life or will he be forced to act & react in order to survive with no honest moment of self reflection? That is left to the viewer to decide. There is one definitive answer provided by the movie: there is a soul, but it takes two shots to kill it.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.