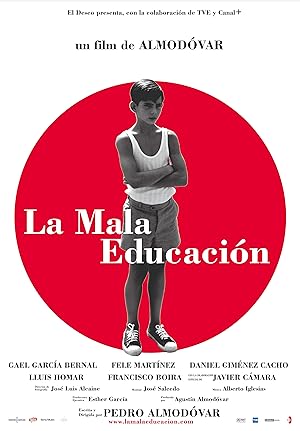

Pedro Almodovar is one of the greatest living film directors, the rightful heir to Hitchcock’s throne with his mix of psychosexual driven dramas and an innovative storyteller who delivers uniquely crafted narratives. When Hulu notified me that his films were going to expire and be removed on June 20, 2017, I decided to watch all his films, including the ones that I already saw. This review is the third in a summer series that reflect on his films and contains spoilers.

I think that you must see Law of Desire before seeing Bad Education even though the latter is more polished and an undoubted masterpiece. Bad Education is clearly an even more twisted retelling of Hitchcock’s Vertigo. Almodovar also seemed to be influenced by the original The Housemaid. When I saw Bad Education, I immediately realized its influence on Tom Ford’s Nocturnal Animals.

Bad Education begins with a director brainstorming about his next project when a mysterious person enters his office bringing turbulent memories of his first love. The film has five major characters: the director, an actor, a priest, and a victim in the present and the past. None of them are cis women. This film’s narrative structure is a Russian nesting doll of deliciously demented confusion, and each story is compelling on its own. There is the director’s point of view in the present real world, his visual interpretation in his mind/for his film of Ignacio’s written story and the priest’s point of view of the past.

The opening credits are a microcosm of this narrative structure as movie posters are ripped from a wall and layered over each other then ripped again to reveal a new name. All Almodovar film lovers must ask if it is real or fiction, and in Bad Education, the answer is yes. Almodovar’s later work confronts the nature of being a film viewer/maker and enjoying a story as if it is real even though it clearly isn’t. We enjoy the pleasure of being convincingly deceived, but paradoxically are outraged when we discover that a character has lied to another character. Almodovar’s skillfully crafted discombobulation makes us ask ourselves what are the rules, what is good or bad behavior and what makes a good or bad person.

Both Law of Desire and Bad Education ask the question of the morality of being a director. Who owns stories? Is it the person who lived it, the messenger, the person who sympathizes with it and keeps it alive? Is there such a thing as stealing a story? Is there such a thing as a story? Almodovar’s later work is deeply influenced by Rashomon. Unlike the priest, Almodovar’s directors are society’s confessionals. People feel compelled to give directors stories and confess their sins with no guarantee of secrecy or approval of the final cut. They do not only seek absolution, but vindication and understanding, i.e. empathy.

Bad Education is littered with many madmen. The younger brother steals his sister’s identity and story, is complicit in her murder, kills his former lover and gets another one under false pretenses, but it is unclear whether it is out of compulsion/jealousy, financial gain or some strange combination of the two. He embodies the worst elements of Cain and Jacob. There is the director who is aware of the deception, but still gives the younger brother the role in some mutual form of psychological torture to punish the younger brother for his deception and himself for forgetting his first love. The winner is the pedophile unrepentant priest, who is sympathetically portrayed in the director’s mind/depiction as genuinely having a depth of feeling for only the young Ignacio, not other boys, while simultaneously showing the deleterious effect of his obsession on his victim in the past and the present. The real priest is colder and more craven than his counterpart. He has what the grown Ignacio wants, but history repeats itself-he will never give it.

There are multiple love triangles, both real and imagined, but calling some of them love triangles seems wrong. It is clear that the priest raped Ignacio. Ignacio and the young director loved each other. Sleeping with someone using a false identity is rape. Is Angel raping the director by pretending to be someone else? Is the director raping Angel because he knows this? Why choose.

Bad Education tackles the image and victimization of a transwoman, played by a cis male actor. There is the director’s imagination and interpretation of a transwoman in a story written by a transwoman. This imagined transwoman is appealing even in her vices and exists as a sexual object—to sexually gratify her childhood friend or an inconvenience to discard. She has hopes, desires and a subversive Les Miserables plan, but they are secondary to the cis men that she encounters. There is the transwoman’s brother’s interpretation of what is an appealing transwoman, which intersects with the director’s vision, but is never confused with sympathy with gay men or transwoman because he casually uses derogatory terms, but not in a loving way because he is not a part of either community even though he does have sex with men. There is the priest’s view of the transwoman author. He is disgusted by the transwoman, specifically her tits, her demands and her drug use. Because she is an inconvenient former sexual object, she is discarded. Her vices are not seen as amusing, but destructive.

Bad Education is a tragedy and is what Law of Desire would have been if Almodovar made it when he was older. Even though it is told from the priest’s perspective, I believe that Ignacio would not blink an eye if she saw the priest and the younger brother in flagrante. Almodovar consciously never shows us an undiluted view from the transwoman’s perspective because he knows that he cannot. It would be a lie. He seems to condemn himself and all segments of society for exploiting transwoman’s bodies, stories and identities then discarding them when they become messy or inconvenient. Society has the power to give her what she wants, but would rather see her dead than be inconvenienced.

Unlike Woody Allen, Almodovar does not see himself as a victim, but as a possible unintentional perpetrator of violence and corrupted media images as a gay man against someone he loves, a transwoman. He acknowledges that even his sympathetic depiction of a transwoman’s story cannot be equated with a transwoman’s story. He is guilty of fetishizing someone’s life, struggles and pain even when he does not want to. He makes her into an object of desire instead of a person. When both the priest and the director read the same story, they are condemned by it. The transwoman receives no love, no connection, no refuge, no justice.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.