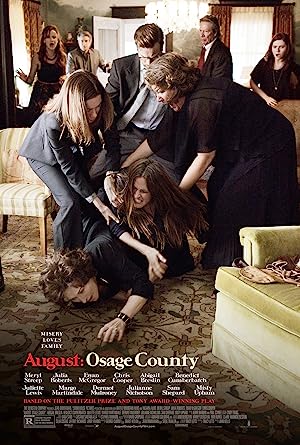

I loved August: Osage County. I initially hesitated to watch it because I thought that the film would be one of those quirky Southern redemptive family fests, but it wasn’t. While watching it, the actors didn’t deliver their lines as if it was a play that was filmed, which is why I didn’t know that August: Osage County was originally a play until I finished it. It wasn’t predictable, but it could have devolved into a soap opera with the familial drama if it wasn’t for two factors: amazing acting from the entire cast and the commitment to unremittingly awful characters from beginning to end. There were no happy endings. It wasn’t like Silver Linings Playbook where crazy turns sweet and quirky. Crazy is soul killing, self-destructive and potentially cyclical for generations if not broken in some way. August: Osage County’s story does not explain everything or wrap up every storyline in a tidy fashion. Why is the matriarch a complete mess? There are allusions to child abuse, but the story isn’t clear and is not offered as an excuse for her favorite pastime: psychologically destroying everyone around her. Each character gets a spotlight-some more than others, but when you have excellent actors, they make the most of the time that they have. I found myself cheering Julia Roberts (don’t worry, I don’t condone all of her character’s actions in the film), who thankfully has abandoned her American sweetheart persona and gone gritty and unflinching in this one. At this point, Meryl Streep should just have an award named after her. Chris Cooper is so captivating that when it is his turn, you as an audience member will stop as if you’re being chastised. I could go on about each actor. While I loved the film for committing to the unremitting suffocation in the atmosphere, other than horror, has any Hollywood film portrayed a man suffering from mental illness in such an unflinching fashion other than horror films? I couldn’t think of one. It does not take away from the excellence of August: Osage County, but it does say something about Hollywood’s view of gender. Masculinity is depicted as something inherently insane so in the end, it can be turned around with the help of a good woman and some meds. In As Good As It Gets, Helen Hunt’s character asks, “Why can’t I have a normal boyfriend? Just a regular boyfriend, one that doesn’t go nuts on me!” The answer: “Everybody wants that, dear. It doesn’t exist.” Even in films like Taxi Driver or One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, two iconically mad films, the actions are depicted as heroic and subversive. So what does it say about Hollywood’s view of women that it can only depict them as realistically mentally disabled?