At Eternity’s Gate has one scene that appears to be done in one take. Paul Gauguin, played by Oscar Isaac, delivers news that devastates Vincent Van Gogh, played by Willem Dafoe, so Vincent runs out of the interior space into the outside and in that instant, the lighting of the scene transforms from warm and brown to blue and cold. What we see on screen is a visual representation of Vincent’s interior life, but HOW did Julian Schnabel accomplish this shot in one take?!? Is it a trick in editing, a barely discernable cut in between the outside and inside scenes, amazing lighting setup?

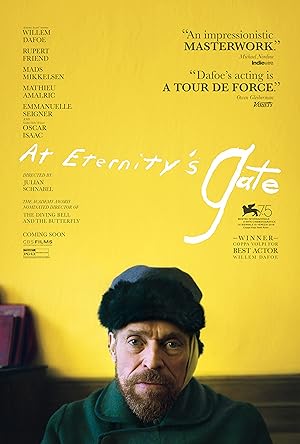

When I saw the preview for At Eternity’s Gate, my friend, who wants to see every movie, reacted definitively and negatively to it whereas I had the complete opposite reaction because Schnabel’s film looks like a Vincent Van Gogh painting come to life. If you are looking for a film to learn more about the painter’s life and know very little about him, then definitely skip the film because it is not a traditional biopic, but if you love his paintings, are not enraged by abstract art and shaky cams do not bother you, then it is a must see film. I want to see it again in the theater and possibly buy the film once it is available for home viewing, but only seeing it on a big screen in a dark theater while giving it your complete attention can do it justice.

At Eternity’s Gate has so many elements that would normally turn me off. I had a real problem with Dafoe playing Jesus in The Last Temptation of Christ, not because he is not a good actor, he is a great one, but he seemed too rooted in the twentieth century, too obviously mad with no ambiguity, too American, too iconic to transform into another iconic figure. Dafoe is not the right age or nationality to play Van Gogh, and if he was going to play him, why not use French the entire time? There are so many actors who came to America without knowing the language, but learned their dialogue phonetically. The movie dialogue bounces from French to English. It uses the How We Got Here narrative device. It sounds more like a philosophical screed than actual dialogue, which usually loses my interest. And yet, I was enraptured the entire time, and it worked for me.

Dafoe’s Vincent may be his best performance to date and the definitive depiction of the artist ever (caveat: I’ve only seen one of six movies about his life). Because At Eternity’s Gate is trying to show how Vincent is different from everyone else, all the elements that usually detract from my ability to lose myself in Dafoe’s performance enhanced it: his madness, how he sticks out like a sore thumb, his weathered face. He also brings something that I don’t recall seeing in his other performances: a tenderness and vulnerability, particularly in his scenes with Rupert Friend, who plays Theo, Vincent’s brother. It is refreshing to see a film in which men are openly affectionate with each other. Also shout out to his sister in law for being supportive. If your sister in law agrees that her husband should give money to his jobless brother after having a baby, she believes in you.

I also appreciated that At Eternity’s Gate threw epic amounts of shade at Gauguin, whom I find distasteful as a person, by depicting him as a pedantic peacock undeserving of Vincent’s friendship and affection. Side note: Isaac is in four movies this year, and I’ve seen three of them, but two apparently weren’t that good. Get money! Using Gauguin as a foil for Vincent further humanizes him. Gauguin is a narcissist whereas Vincent wants to lose himself in something bigger and sees painting as an evangelical act.

At Eternity’s Gate’s philosophizing probably didn’t bother me because it resonated with my spiritual view of the world as a Christ follower (using Christian seems strange in light of how little I have in common with those who use Jesus as a sword, not a shield). I’ve always felt a kinship with Vincent on a basic level because of his first name, but also with the way that he sees the world. The film creates an intimacy by leaving the screen dark while Dafoe’s voice utters Vincent’s relatable words about his place in the world and eternity. I could relate to his transcendental moments of rapture when he finally felt in sync with his smallness in relation to eternity or the infinite. His search for the light felt more germane to my daily life than Terrence Mallick’s To The Wonder because it wasn’t simply discussed, but shown.

At Eternity’s Gate was shot at the same locations where Vincent painted, but to be able to capture on film the photographic or moving picture equivalent of what he saw and painted should not be taken for granted. If we went to those places, it would not be effortless to replicate those images. Simple imitation does not evoke the same feeling that we imagine Van Gogh felt when he was transported to a timeless existence and free from the cares of this world whereas Schnabel achieves that psychological phenomenon in this film. Schnabel has the technical ability to do so and the understanding of how those paintings make him feel then successfully transmit those ephemeral qualities to a different medium and to his audience. He does not simply do so with color, but briefly shifts to black and white to show that the texture of Vincent’s paintings feel like a window on nature, more like sculpture than a two-dimensional painting.

Many critics complain about Schnabel’s use of audio. At Eternity’s Gate is an accurate emotional depiction of the painter, not literal or created to inform, but to empathize. Sometimes when the overblown soundtrack dominates instead of the sounds of nature, the film is letting us hear what Vincent hears when he is in religious ecstasy over the lighting, specifically in the scene in the insane ward when he snaps out of his reverie and the soundtrack goes away once he hears his name. When he shares a still, tender moment with his brother, we can hear Dafoe swallow. The dissonance between the audio and the scene when Vincent replays something that was said seconds before is what any of us does when we are perseverating over a moment and replaying what happened with the major difference being that he is not in full control of this mental exercise. This distortion reflects his internal reality. While watching the movie, I thought every scene with tormentors was literal, but I now wonder if they were manifestations and visions of his internal doubts and critics, especially using children as demons or imps. He is not a reliable narrator, but he is a sympathetic one.

I was incredibly moved by At Eternity’s Gate, but my heart was also open to the experience. Under slightly different circumstances, the film may not have struck me with its beauty. I usually find Schnabel’s work overhyped and underwhelming until The Diving Bell and The Butterfly, but now I believe that he has achieved greatness.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.