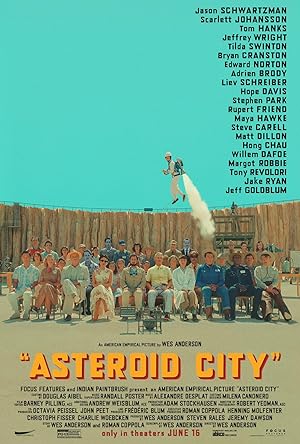

Shot in black and white on a black box theater set in a 1957 television studio, Wes Anderson staple Jason Schwartzman plays an ambitious actor, Jones Hall, who seduces playwright Conrad Earp (Edward Norton) after getting a plum role as Augie Steenbeck in Earp’s last play, “Asteroid City.” This intimate backstory is one of several behind-the-scenes vignettes about the production of Earp’s final work, which is the teal, orange, and tan palette section of the film. Patriarch, recent widower, and war photographer Augie is one of many offbeat parents taking their gifted children to the 1955 Junior Stargazer convention. A brief alien visit interrupts the proceedings, triggers a government-imposed, no travel, no communication with the outside world quarantine and sparks a widespread existential crisis about the meaning of life.

During lockdown, a mutual attraction develops between Augie and fellow Stargazer parent, famous actor, Midge Campbell (Scarlett Johansson). As the play approaches its final act, the line between these two stories gets blurred until Hall breaks character, returns to the black and white world and is desperate to understand the significance of Earp’s latest work. He calms upon seeing a familiar actor (Margot Robbie) who is working on a different project but was supposed to play Augie’s wife. The poignant, stirring moment between the two feels authentic, but they are acting, separate and move on to the next moving scene.

Like Christ’s birth, time has a new marker: before and after the pandemic, and the pandemic’s influence is showing up in movies in a more subtle fashion than the explicit, exploitive “Songbird” (2020). Wes Anderson’s “Asteroid City” (2023) is one such film and note the time gap between the televised portion and the play compared to the start of the pandemic and the “new normal.” By setting a sci-fi dramedy in a different era, Anderson disguises that the film examines the cycle of how a contemporary cataclysm affects people: before, adjustment, “new normal.”

The time before a cataclysmic event establishes what people consider normal even if what the normal classification disguises an insensitive imperviousness to quotidian horror. The titular city’s denizens’ definition of normal is indifference to sensational events such as infinite cops-and-robbers car chases/shoot outs, death of a beloved family member and the occasional atomic bomb explosion, the onscreen embodiment of how most ignore the average news cycle. “Asteroid City” shows that Anderson knows that horrible things are happening all around us. Overlooking the not normal stream of violence helps people function.

The alien visit shocks everyone, gets their attention, and forces them to question themselves. Something unusual is harder to ignore and forces us to deal with our mortality and powerlessness. So why choose an alien appearance as the cataclysmic event? Prior to the alien’s appearance, Augie tells a story about when he met his wife, and she claimed to be an alien. During the middle of “Asteroid City,” Augie and Midge’s children confide in each other that they feel like aliens, strange, not belonging to this world—side note: a common descriptor among autistic people, who could never be diagnosed except as gifted and put on an advanced track thus enhancing the feeling of alienation from those around them. The alien functions like the pandemic by disrupting lives, but also symbolizes loss, death, love, an unusual identity which usually prevents belonging and the vast unknown.

The adjustment period features Anderson at his most political. After the 2016 election of Presidon’t, many filmmakers made films that denounced his positions. While Presidon’t is not Anderson’s focus, “Asteroid City” is the closest that he gets to addressing the resurgence of US fascism. When the government, specifically the off-screen US President, imposes a quarantine on the town, even though the reason is different, it becomes more obvious that Anderson is reflecting on the pandemic quarantine and expressing frustration at the executive office’s destruction of liberties such as freedom of movement and press, but he is also jubilant about the ways that people, especially children, use their intellect to reclaim them: science and art, two fields which fascists hate.

“Asteroid City” captures the positive aspects of the adjustment period. The quarantine provides an authorized excuse to spend time doing what you want and love, throws people together who would otherwise never know each other—if you are of a certain class who does not have to continue working. The children finally belong. New connections have time to develop into relationships, which is where the common ground lies between life during quarantine and the life of creatives making a show. It creates intimacy between strangers.

During a crisis, people also try to adhere to their routine, and Anderson is no different. Anderson’s routine is making movies. Anderson’s average workday entwines fiction with production’s reality, but the difference between the two is irrelevant since both elicit authentic emotional reactions. Anderson depicts this experience by paralleling the creative process with the cycle of how people mentally process a crisis. Anderson’s onscreen proxy is Augie, the photographer, who does not even get ruffled when his wife dies offscreen. “My pictures always come out.” Augie’s emotional state changes after the alien visit though his work remains unaffected.

Encountering an extraterrestrial forces Augie to contemplate his place in the universe and his mortality, and Earp’s death plunges Hall into desperation as he tries to make sense of Earp’s swan song. Restricted from leaving the town, Augie keeps taking and developing photographs while Midge prepares for her next role in their respective, adjacent, separate motel bathrooms. They flirt through their bathroom windows, an image reminiscent of a retro Zoom: strangers exchanging intimate details from their separate square torso dominated boxes. As he helps her run lines, she encourages him to “use your grief.” Another time, Augie engages in self-harm. Augie’s emotional release is an example of Anderson’s departure from his earlier movies’ signature elements and commences a collapse of the invisible wall separating the convention characters and the vignette actors.

Anderson weaves together the two stories then implodes them to play with meta communication: showing the conflict between what people say and do. The 1957 televised portion resembles a play, but the color portion, which the black and white characters call a play, is a movie. It has the feel of the Abbott and Costello routine, “Who’s on First?,” an American burlesque play on words. People see Anderson’s films because they enjoy his visual style, camera choreography, monotone delivered dialogue and oddball stories, but this narrative’s structure may leave fans confused, especially since viewers were expecting the color portion. The black and white section was not used in marketing.

Anderson’s narrative technique serves a deliberate, surrealist, Brechtian purpose: to confuse and disorient thus making viewers conscious of watching a constructed chronicle instead of allowing the story to sweep them away. Anderson’s structure does not permit viewers to forget that they are watching a movie so they can focus on the underlying emotion and overarching message of both storylines: living a contemplative, emotionally genuine life with others is more important than deriving a specific meaning during turbulent times.

By muddying the story, he is forcing the viewers to focus on this message, not relate to a character or a story. I liked the movie while watching it but enjoyed it more after thinking about it. Those who are unprepared to focus more on the structure than the story, a reasonable expectation for movie goers, may hate “Asteroid City” and deride Anderson as a pretentious emperor without clothes. Please reconsider, especially compared to Anderson’s friend and director Noah Baumbach’s “White Noise” (2022). Anderson experimented and made a personal movie, an ultimately optimistic movie that shows at times of upheaval and overwhelm, loss may be unavoidable, but there is a core identity that withstands the storm. “Do I just keep doing it without knowing anything?….I still don’t understand the play.” “It doesn’t matter. Keep telling the story.” It is a great concept that works better than Baumbach’s film, which had superficial faith that the worst events pass and felt like an imitation of other directors’ work. “Asteroid City” understands that cataclysms and the creative process are all about cycles. The structure of cycles and the emotions that those cycles stir up are prioritized over the story and character development.

The adjustment period shows signs of ending when the alien visit is tamed, repackaged, marketed, and sold, transformed into something palatable and scalable. It does not take long before people make an alien visit into a part of the routine, capitalism, a spectacle, a tourist attraction. These scenes allude to the off-screen events that preceded the start of the “play”: how a small, insignificant town reframed a meteor, a small piece of a comet that burns up upon falling and landing on Earth, into an asteroid, which is always found in space and the term changes to meteor after it enters a planet’s atmosphere. There is a buoyant humor to Anderson’s film about disproportionate perception. The alien visit is brief, yet its effect is expansive like the anticlimactic ball-sized meteor’s effect on the town. Small, unusual moments get expanded, have monumental impact then commodified—like making movies. Creating a new normal is an attempt to displace unsettling powerlessness in the face of the infinite unknown’s insignificant markers with wheeling, dealing and diversion.

The final phase, the “new normal” resembles the beginning of the “play”, book ends, mirror images, as if Anderson pressed reverse visually without erasing the substance of the narrative that came before. Becoming accustomed to the existence of extraterrestrials vaporizes that special quarantine space of communion among people who would otherwise never know each other. By the end, though affected, the town appears indistinguishable from its opening appearance as if nothing happened. After the quarantine lifts, Midge is not shown onscreen as if she was never there or had an impact on Augie. Cut scenes are referenced. The playwright dies. Oblivion has many faces. The adjustment period’s visual specialness is lost leaving an emptier screen.

It is impossible for the affected to return to normal. While there is no visible difference between the beginning and end, the lasting impact of “Asteroid City” is emotional for the characters on screen and the viewers in the theater. Acting is not real. The movie is a fictional, stylized artifice, but the fictional people, events, and cycles stir up real feelings. Temporal connections matter and help us to live. The pandemic-inspired film is a commiserating, reassuring love letter to survivors and creatives.