If I have one regret, it is that I did not see And Then We Danced during its opening week. All the movies theaters closed during its second week of showing because of the global pandemic. Is there somewhere that I can send my box office money to so it can count towards this film? If the Commonwealth had not shut down, and I still had to report in person to work, I would have risked my life to see it. I was so eager to see this film because I had seen the previews countless times and often wanted to see it more than the movie that I originally paid to see.

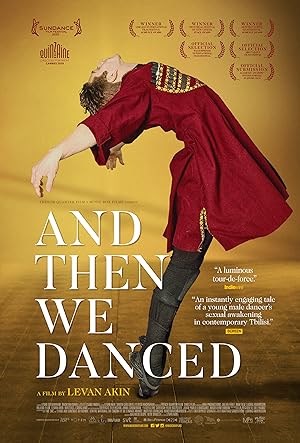

And Then We Danced is about Merab, a third generation, driven and dedicated dancer training at the National Georgian Ensemble on the line between poverty and glory. He lives to dance in spite of lack of encouragement from his instructor, and his family’s living cautionary tale that even a successful dancer does not lead to a financially stable life. When Irakil arrives to replace a dancer, Merab’s life is upended as the newcomer rightfully takes his place as the lead dancer yet Merab finds himself drawn to his competition. As they get closer, he has an awakening which helps him discover what he really wants from life and his art.

And Then We Danced reminded me of what Ian McKellan said about how coming out improved his acting, “Until I came out, my acting was all about disguise, and thereafter it became about telling the truth.” As I was watching this film, I felt that while I did not completely comprehend the backdrop and could not fully appreciate the layers being communicated in this film, I had a sense that by specifically focusing on one incredibly unique individual in a very particular set of circumstances, it was an effective way to communicate the entire region’s political, cultural and religious history while being universally relatable in retaining its humanity through a story of the heart, not the head. The film’s primary purpose is to communicate emotions and experiences thus bestowing the quotidian with a salience that we may not attribute to our daily life while living it.

And Then We Danced really made me love Georgia and feel as if I understood why Merab loves the dance and his home even though it is fraught with problems: living hand to mouth, a disreputable brother, a divided family, a denial of instinct. I loved how the film was rooted in the details and routine of his daily life. I felt as if I understood the shape of his neighborhood: the local restaurant, the downstairs grocer, his nosy neighbor, his friends hanging out at the corner. Through the instructor’s occasional prose dump, it sounded as if a cultural, religious and political shift happened in Georgia (the country, not the US state) fifty years ago, and it upended Merab’s family so they were left on the outside looking in. Even though the film briefly shows sumptuous archival footage of the dance, it was not sufficiently long for me to compare and contrast with the dance that I saw Merab and others dancing to see how it had evolved. Based on the instructor’s words, it sounds as if strict gender norms were imposed upon and sexuality exorcised from the dances. We never explicitly find out why the instructor disapproves of Merab’s family of dancers, but it seems as if Merab is in an uphill battle trying to escape nature and nurture for a relatively young, imposed tradition that asks him to do something alien. A lot of my filling in the gaps is based on memory remnants of Nureyev’s dance style, which is from a completely different region.

On a parallel track, Merab is gay, which is not obvious because it is forbidden. There is a constant sword of Damocles threat that he can lose everything, his family, friends and career, if this aspect of his life took center stage. Up to now, I imagine that it is not a problem because other than one silent male dancer whom I noticed kept finding reasons to sit close to him or studied Merab’s face to gauge his reaction, his circles do not provide many options for his sexual orientation to be more than a theoretical reality. Irakil’s presence is disruptive because it shakes Merab’s foundation. He can no longer pretend to himself that he is the best dancer, that he is not attracted to men, that he has to obey authority or simply live to survive with one indulgence. Irakil opens a world of possibility within Merab that he did not know existed. Before this awakening, there is something pinched and stiff about Merab. He is holding himself back, but after Irakil, he becomes less numb and rote. He opens himself up to emotion. Yes, he has a crush and is in love so that creates room for new experiences and leads to expanding of his emotional palette that he kept shut off—we see irrepressible exuberance, but it is more than the specific relationship, which is beautiful, resonant and perfect. It is about rediscovering yourself and discovering a new way of navigating the familiar.

And Then We Danced wisely refuses to conflate the discovery of self with the relationship and sexual awakening, which many viewers may not like if they were primarily coming for a love story instead of a coming of age story. It is more than sex or a specific relationship with a certain person albeit that person is fabulous. I was rooting for Merab and Irakil. Their attraction was organic, magnetic and reciprocal. Irakil is a perfect partner. He is better in so many ways, but it does not make him superior. It makes him generous, affable and natural. In many ways, he is more mature than Merab with the ease in which he interacts with others and makes a comfortable space for himself where ever he goes. Their love scenes are hot. The real crossroads for Merab is whether or not he allows himself to stay changed and how that will affect how he lives every aspect of his life. Will he compartmentalize himself to have it all? Will he wall himself from emotion? Will he turn into a cautionary tale?

I was really concerned with one plot twist in And Then We Danced when he is on a bus and catches someone’s eye, but it ultimately works because it does not use that moment to reduce his discovery to one, tropey thing, which would have seemed too reductive to his identity and cheapened everything that came before, but is a much needed transition that leads to the satisfying, showstopping denouement. Even though Levan Gelbakhiani is not an actor, and Merab is his first professional acting job, he was an astounding discovery, especially how he acted through his dancing.

If I had to complain about And Then We Danced, unless there was a special significance for the director choosing only to focus on the lower or upper half of his body, I would have preferred long shots to fully capture the entire body through space as Fred Astaire preferred in his dancing sequences. The music and dancing were so evocative that I was frustrated that I could not take it all in. While this movie was not necessarily perfect, it was a sensitive masterpiece that made me love what should have felt utterly foreign.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.