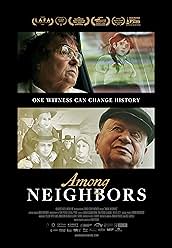

“Among Neighbors” (2024) is a documentary that focuses on the residents of a small Polish town, Gniewoszów, and what their life was like before, during and after World War II. Their stories offer a snapshot of history in response to a Polish law that potentially could suppress any historical account that painted Poland as complicit with Nazi German invaders. Director and writer Yoav Potash crafts a narrative that frames history as a town’s biography with unexpected twists and turns. The biggest twist may be that this documentary advances a handful of stories from ordinary Polish people about their modest effort to help their Jewish neighbors’ and corroborate their stories. Suppressing history means hiding the good and the bad.

“Among Neighbors” is a participatory documentary in which Potash appears on screen interacting with the interviewees or offscreen asking questions. He does not speak Polish, so he often uses interpreters or other Polish speaking people to ask questions. He mainly appears for the flashier moments., big reveals or gotcha moments, because hey, that is what we Americans do. While it is a historical story, it is predominantly a human-interest story. The film is mostly shot in the town, but there are a handful of scenes shot in Warsaw and Givatayum, Israel where one Holocaust survivor lives. Potash interweaves stories from academic talking heads, Polish people or their descendants, so the overall historical context fleshes out the personal stories. It is roughly chronological.

The intellectual talking heads presence makes “Among Neighbors” initially seem like a conventional documentary. They appear to be predominantly Polish. Konstanty Gebert, a journalist, frames the need for history as the antidote for Jewish and non-Jewish Polish people who are not conscious that they miss each other and the former close relationship that they had. Historians Dariusz Stola and Magda Teter offer separate accounts of Poland once being a sanctuary for Jewish people who were threatened in other parts of Europe with conversion or expulsion. Teter goes as far back as 1264. One of the tragedies of World War II is that Poland has been so subject to foreign invaders that the outside world does not often hear about Polish history before that era. Poland sounded similar to how people used to describe Germany as a refuge from persecution.

Here is where Gebert’s statement becomes pertinent, “Victims can do evil things.” The more recent story of Poland is a story of trickle down suffering. Just as the Polish people were oppressed and their stories smothered or twisted, especially while under the Iron Curtain, the impulse to model that behavior now that they are independent is human, but the wrong path. Later Stola reveals how the law personally affected him and draws parallels between that law and global efforts to destroy history, which Teter describes as an “attack on democracy.” As an American outsider, it is rare to see someone able to look beyond their shores to acknowledge international commonality, and it is one of the first of many moments in “Among Neighbors” that brought tears to my eyes. The hate tree grows everywhere, it is only the branches that are different.

There are also talking heads who have more of an overt personal stake in this story. An emblematic symbol of “Among Neighbors” is the Jewish gravestone, and how the Nazis repurposed those stones. Photographer Lukasz Baksik claims to never get taught Jewish history, but when he realizes that this practice still exists, he was so horrified that it became the subject of his work. Aleksander Schwarz, a mass graves investigator, works with the Chief Rabbi of Poland, Rabbi Michael Schudrich, and shows how he uncovers un-commemorated graves. He explains, “we use all sort of tools, but there is nothing stronger than a witness.” The corner stone of “Among Neighbors” is the eyewitness testimony.

Most of the interviews are with non-Jewish Polish residents, and mostly people who have always lived there. The name and birth year are the main distinguishing identifiers for the interviewees in “Among Neighbors.” Only Slawomir Smolarczyk appears onscreen with a younger relative, his son, Henryk, otherwise the rest are interviewed alone. The pair are shot most dynamically moving around the town and their property. The substance of their interviews is mixed, i.e. they do not always paint themselves in a good light, but the overall account is substantiated with personal possessions that they show onscreen and reflect a sensitivity that only fear of reprisals suppressed. There is also a huge surprise of how they relate to another person’s story.

Janina Jaworska probably has the most timid body language. She stands in a doorway and seems as if she will startle easy, but she bravely admits that her home once belonged to Jewish people, and her neighbors still express anti-Semitic views. Zofia Lecka stays outside to discuss this phenomenon with resigned dismay. Janina Grzabalska is shown seated with black and white photos on her kitchen table corroborating the aforementioned accounts about the town being predominantly Jewish and anti-Semitic stories told to frighten children. Jan Zieba tells a similar story, but also references a city clerk, Boleslaw Paciorek, who swam against the tide to save his neighbors. Zofia Skorupska, a stylish woman, is determined to convey that everyone knew what happened. One of the stars of the documentary is Pelagia Radecka, who is determined to tell one family’s story though because she was a child when everything happened, it is challenging for her to remember details accurately.

Joseph and Reva Friedman’s American descendants offer their perspective as outsiders trying to get more information and feeling a great deal of pushback and danger during their first trip when Aaron Friedman Tartakovsky, the grandson and Potash’s friend, (the latter is not revealed in “Among Neighbors”), was fourteen years old. His mother, Anita, also shares her story. This family becomes interested in the preservation and memorial efforts, which gives the locals a chance to express solidarity and courage. There is old footage of Harry Lieberman, a painter who was born in that town, when he was one hundred and two years old so his granddaughters, Erica, Arlene and Elinor talk about him and offer the segue to the only living Jewish Polish former resident, Yaacov Goldstein.

Goldstein tells his and his family’s story completely from soup to nuts except for locating one family member. Anna Przybyszewska Drozd, the director of Genealogical Research at the Jewish Historical Institute, dashes his hopes of finding that person because the information is just not available. While his children appear in the story, they are mostly there for moral support, are not named and do not become integral to the story. By the end of “Among Neighbors,” he seems heavier with the revelations that he does receive. It felt as if he turned diplomatic to not disappoint those happy to restore his past to him and reunite.

While “Among Neighbors” uses many conventional filmmaking techniques, such as exclusive interviews, archival black and white film, montage of black and white photos, news headlines, and contemporary location establishing shots, it distinguishes itself when it uses animation to recreate Goldstein and Radecka’s stories. Contemporary footage transforms and dissolves into animation that is predominantly black and white. The only colors shown are red or blue. The Polish flag is red and white with a crowned eagle. A prominent Jewish in Radecka’s story wears a blue dress with white polka dots. Radecka’s illustrated avatar often wears a ribbon that is red and white, which visually signifies his status, but as her story continues, and she becomes more open about her love for the neighboring Jewish family, she abandons the red and white for blue and white. For a portion of the story, to survive, Goldstein has to hide his Jewish identity, which is depicted as a star of David either beating like his heart or as a nod towards modesty when he is forced to pull down his pants, but signifies how he felt his identity was obvious to anyone looking at him. People trying to expose Jewish people have glowing red eyes like monsters, and naturally blood is shown as red.

“Among Neighbors” proves that while history is difficult, tragic and overwhelming, it also offers a chance to destroy the poison of shame and tell stories of courage or frank confessions. While some of the non-Jewish Polish townspeople seem relieved to finally get these stories off their chest, find peace and stick up for their neighbors, work still needs to be done for more of them to realize that Jewish Polish history is their history and feel a fierce ownership of it as another step in strengthening their independence and reclaiming their nation from colonizing forces. It is a documentary that plays more like a drama than a passionate academic exercise.