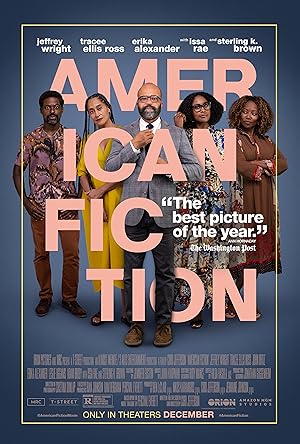

“American Fiction” (2023) is an adaptation of Percival Everett’s novel “Erasure.” When an English professor’s university disciplines him for offending a student, Theolonious “Monk” Ellison (Jeffrey Wright) returns home to Massachusetts to speak at a book festival. When his panel is poorly attended, he wanders into the main hall where author Sintara Golden (Issa Rae) addresses a packed room and read excerpts from her book, “We’s Lives in Da Ghetto.” The spectre of her popularity haunts Monk wherever he goes, and the jealousy eats him alive. When Monk must extend his stay in Massachusetts due to a family emergency, he writes a novel under a pseudonym as a satirical response to literary agents’ criticism that his work is not black enough by including every negative stereotype in his secret novel. When his book becomes a hit, Monk grapples with whether he will enjoy the fruits of his success even though he is perpetuating what he despises.

While most viewers will be attracted to the satirical setup, “American Fiction” is more conventional than most will expect and is a family drama. His mother, Agnes Ellison (Leslie Uggams), is suffering from Alzheimer’s. His sister, Lisa (Tracee Ellis Ross), is an accomplished gynecologist doing meaningful work in a turbulent time but is stretched thin because of the practical demands of her personal life. His brother, Cliff (Sterling K Brown, who appears shirtless and in shorts), is a plastic surgeon going through a second adolescence after embracing a major formerly hidden part of his identity. When Monk is forced to expand his scope from thinking about himself as an individual to being part of a community, he reevaluates his principles.

The central theme of “American Fiction” is Monk wrestling with the image of how he wants things to be versus how they are. Monk has an idea of where he should be in his life versus his disillusionment over where he is. He thought that his parents were happily married, but they were not, and it is only one of many revelations that he faces throughout the film. The dialogue points to the fact that Monk may have been a bit of a golden child so he never interrogated the lessons that he learned as a child and favored respectability politics, but now that he is not being rewarded, he feels resentment over what is accepted and critiques the gatekeepers, the successful and the consumers. He refrains from turning that critical eye on himself until the eleventh hour during the moment that I was waiting for during the entire movie: when Monk finally gets to talk to Sinatra alone.

“American Fiction” depicts the dynamic that black representation should not be equated with diversity or having power. There are two scenes where black people are present and included and have a voice to express that opinion, but it is largely performative. Diversity is still a theory, not an applied reality. Most white voices win and decide what the definitive black experience is and what types of black (hi)stories should be celebrated. While Sintara and Monk are people of education and privilege and relatively powerful to have attained the professional exposure that they have as published, respected authors, the film gives glimpses of behind the scenes wheeling and dealing, which is the most delicious part of the film. The New England Book Association’s director, Carl Brunt (J.C. MacKenzie), scrambles to get more Black authors on the awards committee to choose the book of the year so the Association can appear diverse. Sinatra and Monk’s tastes are aligned, which surprises Monk considering his disdain over her book. In this predominantly white space, they present a united front, but once alone, Monk gently inquires whether Sinatra was exploiting white guilt and putting on an offensive act. Sinatra shuts down Monk’s self-righteousness, “Potential is what people see when they think what is in front of them isn’t good enough.” Monk is dealing with a little self-hatred, which he missed while judging everyone else. This self-hatred stems from being his father’s favorite and cultivating a certain image of himself which appeared flawless, not messy. Cliff has a great line, “He never knew the entirety of me. And that makes me really sad.” The Ellison family is plagued with depression and mental health issues, which are background factors never faced head on.

Even though Cord and Everett do not connect the dots, that is the tragedy of “American Fiction.” Each person, relationship, group is trying to be seen by the other, and what is noticed and celebrated is not the whole picture. In the end, it does not matter whether Sinatra or Monk cater more to white tastes in shaping the product of the Black experience through creative endeavors, they are not deferred to as the experts on the Black experience. They get outvoted. White people decide how people see the Black experience. It does not matter whether intentions are good or bad or Black people are at the table, white people are still the gatekeepers of success, financial stability and access. Outside of family, “American Fiction” excels at conveying how few spaces are available for Black people to be people instead of just spokespeople for a race or under the white gaze. In families and personal relationships, that chasm still exists along gender lines. The antidote is this movie, which for the most part showcases the complexities and contradictions of one Black man’s personal and professional life.

If “American Fiction” has blind spots, it is socioeconomic. The film features a few rom com story lines, one involving Monk and Coraline (Erika Alexander), an easygoing defense lawyer who is a fan of his books whom I absolutely did not relate to in any way, but appreciated and did not have an issue with though it feels surreal to have a woman lawyer be that chill and framed as a love interest. The most tone-deaf one involved Lorraine (Myra Lucretia Taylor), the family housekeeper who is “like family.” Because money is tight, the family debates whether to stop employing Lorraine, which Monk dismisses, and the problem resolves itself because she gets a conveniently timed love interest. The only aspect of life never questioned is that the employe- employee relationship was mutually loving and perfect, which is nice, but rose-colored and dubious. Even the happiest employment relationship has its problems and inequities so of course it was wonderful for the Ellison family. Lorraine appears to reciprocate, but how else would an employee behave under an employer’s gaze. “Passing” (2021) did not pull punches in its brief depiction of the inherent tension between classes even when both the employer and employee are Black. It is a self-serving fiction to pretend that race erases class tension.

In another scene, Monk, the professor, decides to use the N word, he makes a student uncomfortable. Director and cowriter Cord Jefferson and cowriter Everett never spell out the power dynamics, but I will. Monk is arguably more aggrieved over the N word, but the student, a white woman, understandably thinks that the word should be eliminated entirely from his curriculum, which has the effect of erasing the complexity of history. A white woman’s discomfort leads to a Black man temporarily losing his position, but in many ways, she is a displeased employer complaining to the manager.

It is such a treat to get an entire theatrically released film where Wright plays the protagonist instead of getting limited screentime as the protagonist. Was the last time “Basquiat” (1996)? (I’m not counting television movies or movies that went straight to streaming.) Wright is the perfect character actor to play Monk because he is famous and experienced enough for viewers to project Wright’s confidence and credibility onto Monk without being unable to disappear into the character. Monk is an interesting character because he is an entitled man who in fact has not done the work to be successful yet believes he deserves success, but he is not unlikeable thanks to how well Jefferson and Everett write him and Wright plays him. Pacing is everything, and delaying the best self-own admission that he never read Sinatra’s book is key!

There are a couple of narrative structure experiments, which were rapturous in depicting the creative process. While writing his book, Monk interacts with his characters who have materialized in his home office like actors in a play reacting to his direction and expressing their opinion about his narrative plot twists. Another occurs when Monk is pitching denouement ideas to an exploitive movie director, Wiley (Adam Brody). Jefferson shows the idea unfolding as if Monk is living it then cuts back to Monk and Wiley discussing the idea’s marketability. It is a moment of cynical optimism. On one hand, Jefferson has compromised his vision and standards. On the other hand, he is a part of the world and making something albeit imperfect and compromised. It is better than sitting alone in a bath with the shower raining on your head in idealistic despair.