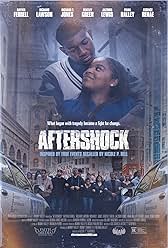

“Aftershock: The Nicole Bell Story” (2025) is based on the true story of how a regular woman, Nicole Paultre-Bell, a fiancé and mother, had to rise after a series of tragic events and become a civil rights leader fighting against extrajudicial executions and sheds a light on how it can be legal for allegedly inebriated cops to kill unarmed civilians only guilty of celebrating impending nuptials. Rayven Symone Ferrell anchors the film as Nicole Bell, the fiancé of Sean Bell (Bentley Green). On November 25, 2006, unidentified plainclothes and undercover NYPD officers shot Bell and two of his friends, Trent Benefield, who may have been revamped to become the character, Kaheem (Frank Adkinson), and Joseph Guzman (Miles Stroter), fifty times. The movie chronicles the steps taken to try to achieve justice and reveals the holes in the criminal justice system. While an uneven film, it still packs a powerful punch so bring tissues.

“Aftershock: The Nicole Bell Story” only cursorily establishes each person in the Bell family and friend group before the crap hits the fan. It may be challenging to even remember who is who other than vaguely a sibling, a parent, a child or a friend. Even Sean is defined only in relation to Nicole as her ideal man, a father and a baseball player, but there is no sense of him as a person that anyone would recognize if he was sitting next to a stranger on a train. It was a surprise that the film actually did the opposite. Instead of whitewashing Bell, the story hinted at possible infidelity early in the relationship and constantly side eyes how he waited to seal the deal with Nicole. It was a risky move, but it makes the movie more credible instead of leaving an impression that this film is firmly on Bell’s side more than the truth.

So, Ferrell has a harder job than the average protagonist because she must humanize and ground the proceedings as the only character fully profiled. Cowriter and director Alesia “Z” Glidewell’s use of repetition and showing how Nicole functions daily does the heavy lifting. “Aftershock: The Nicole Bell Story” may remind some of “Lilly” (2024) except it works. Ferrell adjusts her performance to reflect how Nicole must mature, get accustomed to not being treated like a mourning widow and navigate media and heavy hitters to achieve justice. She goes from an ordinary teenager, a young woman excited for her wedding day to a public figure without losing her humanity.

Congratulations, Ferrell, Glidewell and cowriter Cas Sigers-Beedles! With one simple breakfast montage, you accomplished what Benedict Cumberbatch and “The Thing with Feathers” (2025) could not. The denouement final sequence, which is a time lapse to show how she changes over the years, but how things remained the same, had me in tears, and frankly I’ve been watching higher quality films with more resources and headlining actors during For Your Consideration season, but a film does not need a lot of money as long as talented, earnest people depict a relatable emotion and situation. For Nicole and her children, life keeps going, and the background, infuriating noise is the Herculean effort to remain poised, focused and unrelenting while in deep pain.

Even so, “Aftershock: The Nicole Bell Story” prioritizes recreation and documentation over the human story, which makes it feel more like a made-for-tv movie, which is how it is also classified on IMDb. It will be playing in theaters the day after Thanksgiving. It often feels like the Cliff Notes version of the story, which I remembered even though I have not lived in New York City since the Nineties. Maybe it is just the price of being a Black American to make a mental note of another incident even while trying to just go about business as usual.

“Aftershock: The Nicole Bell Story” took a big swing in deciding to empathize with Gescard Isnora, whom Byron Kenneth Brown Jr. plays, especially in the courtroom sequence when his attorney, Anthony Ricco (the Richard T. Jones), gets a few good licks in to counter the subjective, sympathetic portions of the story, which do not detract from the fact that if cops are credibly and allegedly afraid for their life against three unarmed men with baby seats in the backseat of their car with one is running away, maybe they would be better suited to another profession. The film does allow Brown to express outrage that Isnora may never get to work in his chosen profession again and show his sincere belief in being justified in his actions. The other officers do not get such gentle handling and are more villain archetypes. This movie may be the ultimate example of unconditional solidarity that anyone can expect without pulling punches, but the story also hammers home that Isnora drank on the job, so the filmmakers struck a balance without making false equivalencies, an ethical challenge that most films cannot accomplish.

Richard Lawson is a great actor, and it was terrific to see him. Lawson provides a solid presence like a buoy in a stormy sea as an elder statesman; however, he was playing Rev. Al Sharpton. Movie goers familiar with the real-life person will not notice a resemblance in spirit or body. Perhaps Lawson was too reserved in his portrayal of such an iconic figure, or he was depicting Sharpton as he behaves privately with the people who rely on him, but there was no discernible switch when he was in front of the cameras to a more bombastic side. Maybe no one can play such a unique individual. Similarly, whoever played Larry King, whose performance is only displayed on a television monitor, only wore the clothes, but did not vocally or spiritually capture the man’s essence. In the case of King, it would have been better to get someone with the right accent even if they did not physically resemble him.

Ultimately, “Aftershock: The Nicole Bell Story” makes a powerful point about the frustrating need for incremental change and the power of protest. There is a wonderful scene when a protestor holds up a sign, and the stone-faced response is a tension reliever. I even learned something in that final sequence. There were fewer extrajudicial executions in places where Black Lives Matters protests occurred. Also, by using Isnora’s outrage when he says, “I thought justice was done today because we did not break the law,” it highlights that if it is legal to kill an unarmed man having a bachelor party, then the law needs changing. That final sequence showed what changes were made although nothing will be enough if authorized people with guns are more anxious than unarmed people in similarly dangerous circumstances such as food delivery people, cab drivers, truckdrivers, food service managers and retail workers. No one deserves to be shot on the job, but no one deserves to be shot if they are not a credible threat.

“Aftershock: The Nicole Bell Story” is probably a preach to the choir movie. Its audience will likely be the people who do not need to see it. While it is certainly flawed, it is also meaningful and emotionally powerful. Try to support the film and cause by seeing it in theaters so there can be more resources for filmmakers who want to make stories about real life heroes who should not have to be and just want to live normal lives.