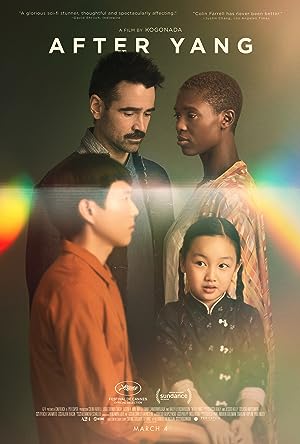

Up-and-coming “Columbus” (2017) writer and director Kogonada suffers from a sophomore slump with “After Yang” (2022), a film adaptation of Alexander Weinstein’s short story, “Saying Goodbye to Yang.” A post twentieth century family’s technosapien manny/son, Yang (Justin H. Min), breaks. Disconnected dad and husband Jake (Colin Farrell) tries to get Yang repaired, learns more about Yang’s life outside the family and winds up appreciating life more through grief.

“Columbus” was my favorite movie of 2017. I watched it in theaters repeatedly and own the DVD. When I saw the preview for “After Yang,” it was only my trust in Kogonada that made me willing to give the subject matter a chance. The ambitious story tackles controversial topics but the writer is oblivious to sitting on explosives: adoption, culture, heritage, misogyny, slavery, cultural appropriation. I understand that this story is supposed to be a meditation on the nature of existence and connection, but the film brushes over a lot of things to get there, and I just could not take that journey with them even when mollified with the Benetton family: the aforementioned Jake, Kyra (Queen and Slim’s Jodie Turner-Smith), adopted daughter Mika (Malea Emma Tjandrawidjaja) and Yang, who was created to look Chinese.

A future society does not have to look like “Blade Runner” (1982) to be dystopian, but this movie sidesteps that tension. If a family buys an alleged member with the belief that this purchase exists only to serve them, then is that member enslaved? The film echoes Antebellum slaveholder sentiments of treating the enslaved as family, and multiracial casting does not dodge that problem. Would the enslaved person agree? Characterizing a servant or an enslaved person as family is not something that should be taken at face value or find reassuring. “After Yang” reveals that Yang hid his past and interests from the family yet clings to the idea that this family’s love was authentic. Jake’s emotional journey transforms his relationship with Yang from bargain shopper given a lemon to finally calling his purchase his son and seeming as a viable being. The film does not get that this revisionist history is problematic. In death, Yang is still a consumed commodity to suit his owner’s moods instead of being given the privacy and unknowability that people must grapple with when loved ones died. Through consuming his memories and life, he is a mirror to admire themselves in.

“After Yang” never addresses the tension of Yang’s existence in life. When mom Kyra (Queen and Slim’s Jodie Turer-Smith) comes to his room, Yang offers to dispose of his hobbies if it annoys her. Yang expects to be rebuked for taking up too much space. Kyra answers that she does not mind instead of reassuring him, “This is your room. You’re my family. You can do what you want with it.” If Yang was family, he would not need her permission to have hobbies, especially since Yang’s functional role is adult. Yang exists to care for Mika and teach Chinese heritage culture to her. Jake calls Yang his son, but he also asserts, “Yang belongs to us,” which is literal and has unintended creepy connotations for the implications of family and ownership. Only Yang’s secret life separates him from a stereotype of a sexless, wise, somewhat mystical Asian man who exists only to serve a child. Yang’s secret life indicates that he felt enslaved and did not have a right to an existence outside of his family. Kogonada shows that the real problem is that Yang had to fill the vacuum that Jake left and acted as a substitute parent/father, not a son. If he was a son, he would be a victim of parentification, a concept that never occurred to anyone while making this film. Jake must fill the gap that Yang leaves behind.

“After Yang” introduces a provocative, but underexplored idea whether a machine can be programmed to teach a child her culture and heritage. This movie accepts this function without question, but it is a provocative idea. What kind of people are responsible for programing technospaiens like Yang in the future? Who decides what culture and heritage are? Were those programmers educated in a world where everything is called critical race theory for just teaching history or filled with anti-Asian bias? Kogonada gives viewers a glimpse of this bias when Jake and Mika visit a repair shop. It is horrifying that Jake has brought Mika to a place with “Yellow Peril” and “There is no yellow in the red, white and blue” on the bulletin board. It is a subtle allusion to bias, but it is a blink and miss it moment. It is a possible transracial horror story that a dad has placed his daughter in danger and has no idea. Also there is a beat when Yang is considered a spy. Two Kogonada films suggest the normality of being the only Asian person in the room. This future seems post-racial, but it is still a world where a family must buy an Asian looking creation because no Asian people appear to live in their neighborhood, and the family does not have Asian friends or family. This family is a vacuum without a real sense of community or extended family, which may explain Jake’s detachment. By exploring the specifics of whether Yang is an effective solution to Mika feeling secure, the film could have elaborated on the lack of community for all the characters.

“After Yang” reduces Yang’s existence to develop Jake, but to be fair, every character exists to make Jake interesting as he goes on a scavenger hunt. Unlike “Columbus” where loss changes people who are interesting and have solid pasts, presents and futures, Jake is a blank canvas to project upon. There is a difference between feeling disconnected and being poorly written. Jake is not the only one suffering from lack of development. What does the mother do for a living? Do they have extended family? Other than online dance competition, Yang is the family’s sole connection to others outside of work or school. There is no world building for the community. Why is not Yang the protagonist? People do not exist in a vacuum. Technology becomes a substitute for community.

Even though Yang takes a backseat to Jake, “After Yang” demotes Mika unintentionally replicating a dynamic that took place in twentieth-century China—preferring sons over daughters. By Jake being more invested in Yang over his daughter, the story is replicating that misogynistic dynamic, but the film frames Jake’s interest as inspirational, not disturbing. The neighbor is more concerned with how Mika is handling the situation than her family. The film misses a huge opportunity to explore how Mika defines herself. If Mika is supposed to identify with Yang because he appears Asian, does she also relate to him in other ways? Does she realize that she is a human being or does she associate her ethnicity with being an object? Even if unintentional, the film links adoption with purchasing an object. This commodification of family links adoption with objectification.

This verdant, but listless movie will have viewers questioning which characters are synthetic. Their subdued manner is not framed as a negative like “Stepford Wives.” Even though this future looks civilized and calm, this family lives in a country where even if the mother is the bread winner, the school still calls the mother first when the child needs to be picked up, and the emotional and mental load of maintaining the house and caring for the child falls to the mother to assign to the father. “After Yang” is trying to make the point that Jake is disconnected from life as the reason for his lack of involvement, but it is not a distinct character trait from an outsider looking in. Congratulations, you’re a dude in a patriarchal society.

“After Yang” appears to contradict itself in the way that Kogonada depicts Jake, a tea hipster. This cast does everything to fill in the blanks, but it is no substitute for good writing. The story introduces bigotry against clones, and Jake may be the Archie Bunker of that time as supporting characters peg him for his prejudice and shun him for it. Jake seems furtive and controlling as he unilaterally makes major decisions about an individual whom they allegedly consider family. Farrell’s take on Jake seems to indicate the opposite. Farrell chooses to use a gentle and soft-spoken demeanor to highlight his character’s steel and an unwillingness to buckle when facing a physical threat. Who is this guy? Why did he lose himself? Why is he finding himself again? Did something get lost in translation from page to screen? By having Jake explore Yang’s life instead of exploring what caused him to disengage from the life that he created, even a superb actor like Farrell cannot do much with this blank slate of a character. Points for an excellent Werner Herzog impersonation.

“After Yang” has a few strong assets. It is gorgeous. Kogonada’s directing is still strong: the way that he directs people to move through space, the composition and framing. The locations are their own characters from the shady repairman’s grittier retro look to the more futuristic spaces which feel Asian inspired. These locations are more interesting than anyone who talks. Yang’s memories have a Terrance Malick aesthetic while remaining rooted in familiar technological visual shortcuts. The clothes were exquisite. The cast add more substance to the characters than the script. Haley Lu Richardson, Kogonada’s muse, does a lot with an unearned plotline that packs an eleventh-hour melodramatic punch.

“After Yang” benefits from repeat viewings, but it was disappointing and underwritten. After building up the threat of law enforcement for Jake’s exploration of Yang’s past, it is just dropped like a forgotten hobby. There is an understated way of exploring sensational topics, but this film failed to recognize any controversy and reduced issues to platitudes. Instead of comforting, it was disturbing. I am still excited to see Kogonada’s next creative venture, an Apple series, “Pachinko” (2022).