If the world was a fair place, Song Kang-ho, one of the greatest actors of our time, would be a household name. He is a Korean actor whose range is vast, and his ability is infinite. Even though I have been watching him for years, I would be lying if I claimed that his name springs to mind when I see his face, but I know and love him in everything that I have seen him in, my Western prejudice with only being familiar with European names be damned. I look forward to a world where Song and others like him finally take his rightful place. He stars in A Taxi Driver as an everyman absorbed in his considerable personal woes when he is forced to look critically around him after a coveted passenger opens his eyes to the government’s abuses against his people and feels compelled to do something about.

A Taxi Driver is proof that just because I know that I am being emotionally manipulated does not mean that I cannot be emotionally manipulated. This movie is the ET of historical drama films as it dramatizes South Korea’s 1980 brutal military repression of people’s reaction to a coup. It starts off slow and takes a disproportionate time to gather momentum, but once it does, the filmmaker and Song have successfully ensnared its viewers into relating to the titular character and the people of Gwangju, the spearhead of resistance against the military.

While there actually was a taxi driver who snuck a German journalist, Jurgen Hinzpeter, into Gwangju to investigate and report to the world that it was not the people who were violent, but the government, the rest of A Taxi Driver takes great liberties with the actual story. The film intentionally dumbs down Kim, the taxi driver, to make him more concerned with practical concerns over principles because he is the proxy for the viewer, just here to live your life until you are moved by others’ decency and bravery. We travel the same emotional arc, which is ultimately why the movie works.

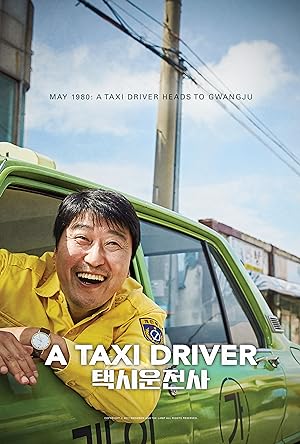

One of the less obvious alterations to the story is that the actual cab was black, not green, but because the film starts in the spring and ends in the winter, it is one of those artistic choices that visually furthers the narrative and culminates in the denouement to an unexpected though completely fictional crescendo of conventional action. A Taxi Driver uses the season as a symbol of the awakening of ordinary people to act as a unit instead of as individuals.

I did not expect A Taxi Driver to elevate the titular profession as a solemn duty and calling that democracy depends upon. Kim initially only cares about his fare, his reputation and the condition of his car, but shows traces of selflessness and consideration that play a pivotal role later in the film as he shows kindness to pregnant ladies or carefully and silently ties his daughter’s hair with a bow. Song imbues these moments with such depth of feeling that when these moments are gradually expanded, instead of hurling things at my television screen in aggravation of such naked attempts to pull my heart strings, instead I silently note the theme in appreciation. Apparently I am not made of stone.

While Hinzpeter is an essential part of A Taxi Driver, he is also the central problem of the movie because he never feels like a three-dimensional person, but as a catalyst to Kim’s change as a person, which is extra weird considering that while the movie starts with Kim, it really ends with Hinzpeter, whom we essentially feel nothing for until we get a brief clip of the real person behind the character. Hinzpeter does not understand Korean, and the majority of the film’s dialogue is Korean so at the end of the film, when he claims that Kim is his friend or when Kim confides an intimate story probably never shared with anyone in Korean, it is not quite believable except in an odd couple in a fox hole under fire way. As the ignorant American who only speaks English in a room full of people having a great time speaking in multiple languages, it has not had the effect of drawing me closer to people. Thomas Kretschmann plays Hinzpeter, and I have actually enjoyed him in everything that I have seen him in including but not exclusively The River and King Kong, but either he has reached his limit, or it was a thankless role.

As an American, even though the movie takes great pains to show why a foreigner has to play an important role in A Taxi Driver and predominantly focuses on Korean characters, it makes me shudder at the unintentional similarities to Driving Miss Daisy. He is essentially a tourist while the people who live there are actually the ones risking their lives to help him break the big story. The movie hurls scene after scene of characters reassuring him that they want him to do it, and there is one disturbing scene at a local paper that does suggest that he is their only hope to alleviate the optics, but it still feels problematic. I do not need a Western character to relate to a universal story of oppression, and while this story absolutely deserves to be told, I have to ask if it is the only film depiction of this time or one of many? If it is the prior, then cynicism is at play though it does not ruin the whole movie.

After 2020, the Ferguson uprising in 2014 and earlier civil rights movements in the US, movies like Roma and as the political backdrop of most Pedro Almodovar movies, A Taxi Driver is at its best when it is focused on ordinary people puzzled by the callous treatment they receive, and the universal images of brutality on the innocent. The initial deliberate pacing of the movie is designed for us to gradually get lulled by normal life, charmed by the Gwangju paradise created in the shadow of suffering when Gwangju life is compared and contrasted to life in Seoul then startled by violence until we are completely consumed by it and angered because it is a destruction of an Edenic possibility. It makes the impulse towards action sequences more forgivable though less credible in the denouement. The images of suffering are universal, which is probably why China, the site of a lone man blocking a tank in 1989, has never allowed this movie on its shores.

A Taxi Driver’s goal is to get ordinary viewers willing to risk their life and sacrifice their financial well being to help redeem others’ names from slander in the name of truth and democracy, which are vague concepts until they are equated with ordinary life imbued with the challenge of what would it be like if no one wanted for anything and everyone’s needs were met. What if everyone is treated like family? We are Kim, but our goal is to become Hwang Tae-sool, whom Yoo Hae-jin perfectly plays and complements Song in a way that Kretschmann never quite manages to do. I found the film to be an inspirational piece of propaganda in spite of its flaws