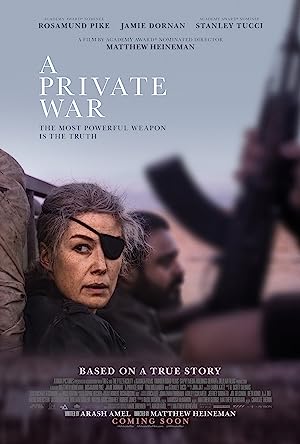

A Private War is an impressionistic biopic of Marie Colvin’s life from 2001 through 2012. Colvin was a war journalist who lived in London and worked in the war zones of our time. Rosamund Pike disappears in her depiction of Colvin and may be the first solid contender for best actress at the Oscar’s next year.

I didn’t know much about Colvin going into the movie. I don’t read The Sunday Times, and I don’t have cable. I only heard about this movie when it opened, and honestly it sounded grim. I dragged my feet going to it, but when my own life feels overwhelming, it is a bit easier to swallow other people’s pain for perspective.

In spite of A Private War starting with my least favorite trope, the How We Got Here narrative device—it starts with an overhead shot of the final scene in the movie—I actually enjoyed the artistry of the movie and thought it was a wise choice instead of a trite, overused one. It acted as an unofficial countdown for the viewers as each segment begins with the location of a work assignment, the year and how many more years were left before we reached the end of the movie. It simultaneously added tension and reassured me. Even though the format may feel as if it is the cinematic equivalent of the stations of the cross for people more familiar with Colvin’s life, the movie’s approach to and Pike’s depiction of her life never feels trite, exploitive or repetitive.

A Private War avoided the melodramatic landmines in her life in the understated way that it explored Colvin’s issues. As a viewer, I’m used to people using these issues to stage some elaborate intervention, the actor gets to chew scenery and act tortured then we get some inspirational speech about reaching the other side. This movie does none of that. Colvin suffered from PTSD, which means that even when she was not in danger, something benign could trigger a memory and suddenly she could feel as if she was reliving a moment or several moments from different points in her past. Because she is a war reporter, and we’re watching a movie about her, we’re not sure if we are watching something unfold in the past or a memory unless we pay attention to the rhythm of the editing because both are equally plausible. It is a great empathetic technique that helps a viewer view the issue and the person seriously because there are no pat answers or obvious trajectories. There are good days and bad ones, but no resolution.

A Private War remains faithful to its subject by showing a textured depiction of what a private war looks like. It shows scenes of her bravado with her friends as her friends (pretend) to buy her recovery while occasionally giving glimpses of uncertainty and wanting to crumble because they know better. Then the movie intercuts with the moments when Colvin is alone and filled with contemplation at what was lost with flashes of the past trauma. What I loved about this depiction of Colvin is that she always does what we want her to do as the hero while Pike simultaneously projects on her face the other way that it could go, the less heroic way that the average human would take then pushes past it.

Colvin explains journalism and why she takes insane risks, “This is the rough draft of history.” When we think war reporter, whom do we imagine in that role? A Private War also has that same ambition—to capture our imagination, correct our default assumptions and replace it with as close a proximate to reality it can create. A war reporter is Colvin, a woman who can be hurt and have demons, but still face danger to tell others’ stories.

A Private War seeks out to do what Colvin did, “I want people to know your story.” It uses her life story as a way to briefly tell the stories of people in war torn countries. It takes people interested in her or the idea of a woman in the role of a war reporter and tries to make us feel how she felt through the excellent dissonance evoked by the editing. This movie was not actually shot in the locations where Colvin reported, but it is easy to forget that you are watching a movie. Come for Colvin, stay for a glimpse into iconic moments such as the eventual downfall of Qaddafi.

A Private War is brilliant because it always shows rather than tells, which means dangerous situations never seem sensationalized or recreated. It is only after the scene unfolds that I began to grasp that a move was risky or could have gone completely south. I remember both Iraq wars, and the movie helped me understand why being an embedded reporter is journalism light. There is a documentary, understated feel to this movie. Instead of belaboring the point that she is a woman in a space mostly occupied by men, these moments feel earned and organic. It was refreshing to see a woman depicted naked or partially undressed, and it never felt sexual even when it was sexual. It isn’t meant to be titillating for the viewer. The camera does not ogle her. It treats her like a person.

A Private War is also breathtakingly free of judgment. People want the best for each other, and they also want what they want for themselves, which is the only source of conflict in this movie. In contrast to Bohemian Rhapsody, which is the moralistic polar opposite, interventions are necessary, but tempered. Tom Hollander, whom I’ve adored since Rev., is stunning in both movies with his nuanced approach to gatekeeper roles that are usually played in a stuffy or tyrannical way. Nikki Amuka-Bird, who plays the black best friend, Rita Williams, was how Mary should have been to Freddie Mercury. Because Williams is based on a real life person, she has a full life outside of her friend. Occasionally when I go to movies, I try to see who I would be in the movie, and I have literally been Williams: leaves parties before everyone else because she has responsibilities the next morning, concerned about friends, etc.

A Private War also deserves some kudos for introducing a new young (woman) reporter who covers the same topics, but there is never a rivalry between the two. They are just depicted as colleagues who travel in the same circle. A more conventional movie would have created a fictional confrontation. Jamie Dornan as a freelance photographer and her right hand man is great in the role, and I was shocked that it was the same actor who plays Grey in the Fifty Shades franchise. Dude, you’re actually good! Everyone has bills. I was relieved that it is depicted as a collegial work relationship and never descended into a trite romantic angle. Movies don’t care about what happened in real life, but I was grateful that the movie treated work and romance like church and state-separate spheres.

A Private War is an easy movie to take for granted in its excellence because it feels like real life, but it isn’t. It is the first drama clearly going for an Oscar. Matthew Heineman’s first feature film feels like mid Denis Villeneuve.