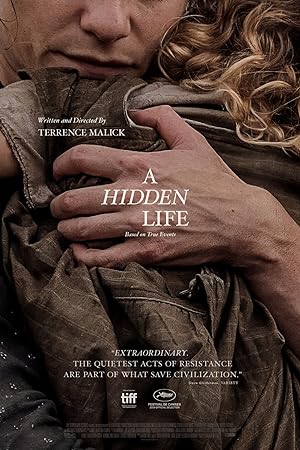

When I saw the preview for A Hidden Life, a true story about Franz Jägerstätter, a Catholic Austrian farmer, husband and father of three little girls, who must choose between swearing an oath of loyalty to Hitler or God, I immediately knew that I wanted to see it, but when I noticed that Terrence Malick directed it, I started to run the other way. I have only seen two of Malick’s films and was not into either of them, but was not sure if the fault lay with me or him. I remember very little about The Thin Red Line because I watched it during my last move, was probably too stressed and distracted to appreciate it. I have already detailed my feelings about To the Wonder. Essentially To the Wonder may have fallen short because Ben Affleck is not a strong actor.

I decided to see A Hidden Life in theaters because a group from church was interested in seeing it, and they were not bringing any preconceptions about Malick so I hoped that they would be able to influence me and help me see his work through their eyes. While they definitely helped me to see the film in a way that I would have missed, I have concluded that you should not see Malick’s films at home. You need to see them on the big screen without distractions or interruptions to fully appreciate the majesty of the world that he is trying to convey. On a small screen at home, you cannot appreciate the way that the sun falls on the living and inanimate objects. You cannot hear or notice if water is flowing, stagnant or makes no noise because it is frozen. You may take for granted the lush green of the fields or not appreciate the weeds in a prison yard. Malick uses these understated moments to depict how God communicates with human beings and shows whether or not human beings recognize and accept His presence.

A Hidden Life depicts Franz and his wife, Franziska/Fani, living as close to the heavens as possible, but still subject to a fallen world. One of my friends mentioned that the environment influenced their capability of making the right decision. Malick’s films seem to suggest that God’s love is best embodied on earth by a couple then this couple’s simple life and communion with nature suggests a deeper relationship with God than others though they still care for the people around them, but by virtue of not being enveloped by their neighbors, they are not as influenced by them. The incursion of the city into their world is the realization that evil has entered their neighborhood, their neighbors, but welcomed happily and enthusiastically. It is a real life horror film, but unlike a horror film, the supernatural or technology cannot be blamed, only people turning away from the true voice of God to the anti-Christ, an ever changing figure throughout time. In this movie, the anti-Christ can be literally interpreted as Hitler, but Malick also depicts it as the man-made flame that people gather and shout around at night, the spirits in the glass mug that embolden lies about existence, the business and trappings of bureaucracy cloaked in authority and uniforms in contrast to the humble work in the fields and the maintenance of the parish church. It is the human desire to inflict pain upon others to elevate oneself rather than endure suffering or be satisfied with one’s lot.

A Hidden Life is two hours fifty-four minutes, which is a daunting runtime that went by quicker than I thought it would although one man tapped out just as the end was within reach. It allows the viewer to empathize with Franz and Fani as we see how their bucolic Eden has no angels with flaming swords to protect it from war planes flying unseen above them. The further they are forced to move away from their farm, even to somewhere as close as their home village, they realize that few have noticed the transformation from harmless hamlet to denizens of destruction. When the mayor claims that they were in chains before, he truly believes it, but we have seen the truth. They are in chains now.

The central question in A Hidden Life is defining what is the right thing to do. Other characters try to make a required element effectiveness—will it make a difference. Franz and Fani are eager to return to normal life, peace, but plagued by their people’s lust for war and are haunted and struck by how dramatically things have changed-the presence of men in uniforms, their fellow villagers adopting their dress, the way that they greet each other or toast. Eventually the tone escalates to the point of physical and psychological violence. It reminded me of the Biblical story of Ruth and how vulnerable her life was as a foreigner having to rely on others for survival as she entered their midst except these characters have known each other all their lives, which makes the transformation closer to a situation from Stephen King’s imagination. Also there are echoes of Moses living near a mountain so he can draw as close to God as possible.

Malick’s sympathetic characters usually speak English, but when they become hostile, they speak German, and Malick provides no subtitles. The only exception to this choice is the final letters exchanged between the couple, which are read in German as if to imbue their final moments with some tenderness and privacy. Even though Malick’s chosen protagonists are Austrian German, because his imagined audience is English, and English speaking audiences normally equate hearing German spoken in movies as aggressive, he exploits our cinematic historical experiences. It is the most conventional element to his movie. I loved when Franz asks Fani, “Did they hurt you…with their words?”

A Hidden Life defines the right thing as quiet, undramatic, small moments of resistance: refusing to rejoice with cruel victors, not saying heil Hitler, not drinking with someone, but also not expressing one’s disapproval in a condemning fashion just simply withdrawing, disobeying the church without shunning its fellowship, not running away from the reach of the law, being willing to accept consequences of one’s faith, treasuring the beauty in the midst of persecution, not defending oneself, even in one’s weakness, committing to small acts of kindness, praying and keeping the faith even when prayers do not get answered in the way that you want them to be answered.

While watching A Hidden Life, I would recommend that you ask yourself who you would be in the movie. I think that a lot of people see themselves in Franz and Fani, but if you look at your life now, would it look even remotely similar to theirs? Unfortunately we would be lucky to be the miller, the parish priest, the in-law, the madman, the widow, the elderly helpful woman on the street, the runaway hiding in the woods, the prisoner or criminal. Are we actually the unfeeling bureaucrat, the judge, the defense attorney, the angry villager, the prison guard, the executioner, the soldier, the postman thrilled to be wearing the evil uniform, the thief? Do we see the beauty and freedom of death as we revel in the joys of life?

A Hidden Life is a visually arresting, unconventionally edited film that could prove challenging to the average movie goer, but if you are someone who enjoys thought provoking movies and are open to watching an art house, period film set during World War II, I would highly recommend that you see it. It also features one of the final performances of the dearly departed Michael Nyquist as the Bishop and Bruno Ganz as the judge.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.