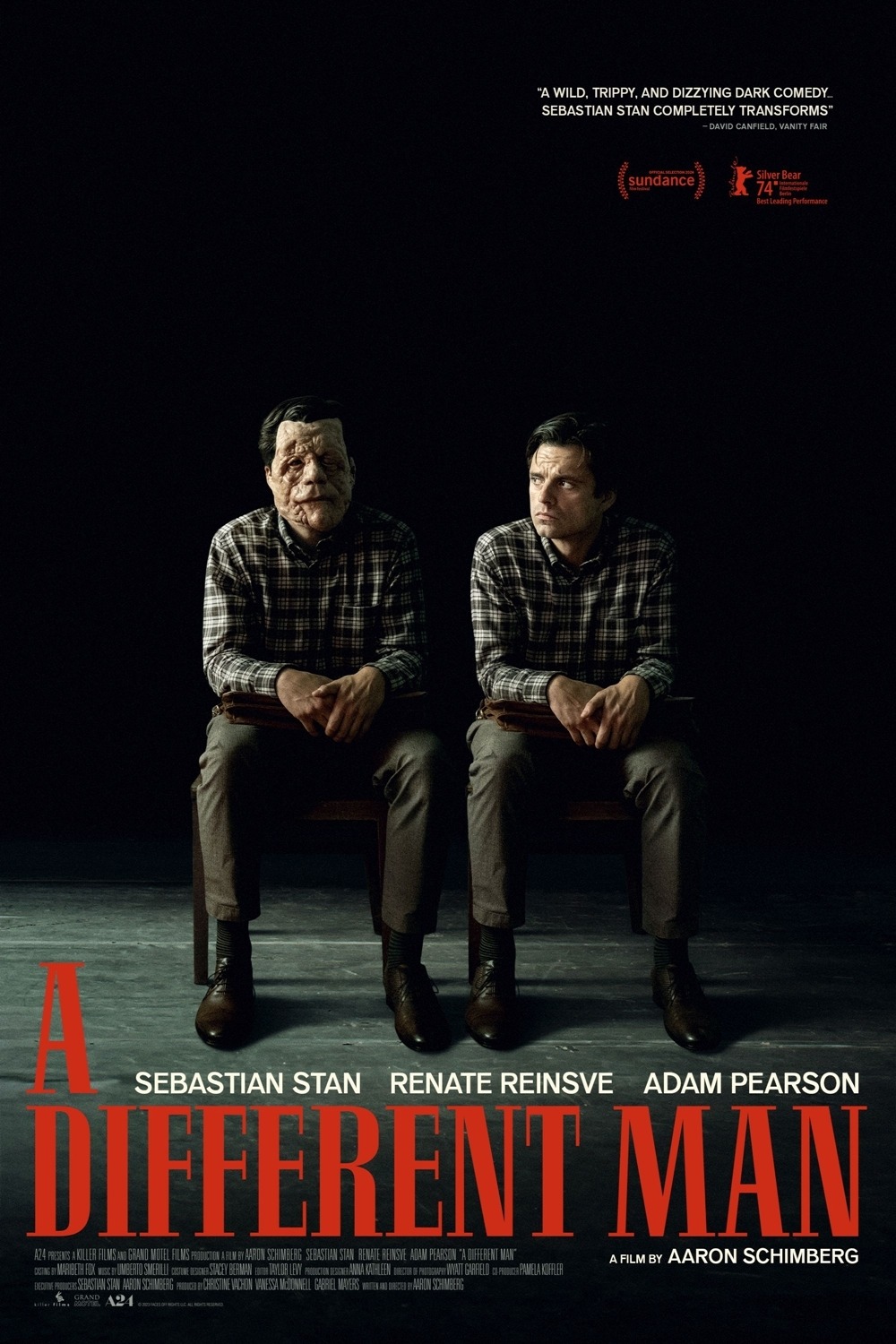

“A Different Man” (2024) stars Sebastian Stan as Edward, an actor who has neurofibromatosis. After undergoing an experimental treatment which reverses his condition and changes his life, the stage calls to him when an off-Broadway playwright, Ingrid (Renate Reinsve), holds auditions for a play that his former life inspired. Just when all his dreams seem to be coming true, finding a way to live both lives simultaneously, Oswald (Adam Pearson) enters and is better at living without changing his appearance, which makes Edward spiral and have an identity crisis.

Edward is a passive man and a bad actor who is barely adequate for training videos. His unspoken mindset is that his life would be better if he was not different or that his looks would change how he acts, and it does initially, but writer and director Aaron Schimberg reveals through Edward’s surroundings that there will always be something off. His apartment ceiling gradually deteriorates over the course of the first act. In the second to third act, his contemporary, open concept apartment is perfect, but when looks are insufficient to prop up his confidence, a huge roach appears. Regardless of his looks, he will always be Edward, and his reinvention is superficial.

Ingrid is an interesting, unwitting bridge between these selves. She knew Edward before the transformation and does not recognize him when he reenters her life. As Ingrid, Edward’s neighbor, she exhibits mixed feelings with Edward: warm, boundary-pushing, a constant presence but ultimately unwilling to initiate taking it to the next step. The unanswered question is why. During rehearsals, a theory about how love changes the way that a person looks at another may hold the key to the way that she appears different to the moviegoer since “A Different Man” is told from Edward’s point of view. Once Edward becomes stunning, she treats him like any guy in her life, and as the playwright and director, she may be a surrogate for Schimberg, who could be self-deprecatingly meta about the lack of creative integrity behind fiction and appropriation of other stories. She is an empty vessel willing to put in the work, but incapable of any original thought. Her stage surrogate is way more straight forward in her approach to life than she ever was. Unlike Edward, she can buy her confabulations, and she never gets shaken because if Edward calls her out, he will reveal his true identity.

With the controversy over Blake Lively’s acting ability in “It Ends With Us” (2024), i.e. her inability to play a role unless the character feels similar to her, including the way that she dresses, “A Different Man” explores the idea of what it means when a role was made for somebody. Obviously, Edward is the expert of his life so when Oswald enters the scene, it initially feels as if he is deliberately throwing Edward off his game by not allowing Edward to keep his two worlds separate. Edward is suspicious of Oswald’s constant and increasing presence, but as the movie unfolds, Oswald is that bon vivant who knows everyone, is comfortable in his skin, is a better actor and practically looks the part. Does someone have to look like a character to play that part? It helps. Is Edward appropriating or being treated unfairly because he does not seem credible as an expert on this character based on his looks? At the end of the day, acting is key, and Oswald’s looks are not his lead asset. Edward cannot memorize the lines though he has the character’s interiority correct. He was born for the role, but he does not have the skill or the right motivation. It explains why most movies, except for “Sing Sing” (2024), that feature real-life people playing the onscreen version of themselves, suck. It is worth noting that occasionally, it seems as if Oswald knows more about Edward than he should as if he knew about the experiment or his true identity, but there is no objective evidence other than his suggestions and comments being too on the nose to be an accident.

Once Edward accepts that Oswald is the better man, his jealously transforms into self-loathing and fierce, unnecessary protectiveness of Oswald, which is really just delayed rage for his early self’s inaction. If “A Different Man” is a tragedy, it is because it proves the adage, “Wherever you go, there you are.” Sometimes the problem is you, and Edward must accept this. If Schimberg falls short, the film feels wanting because the pacing is simultaneously too deliberate and leaps over transitions to get to the sizzle, not the steak. How does Edward live a life worth living once he recognizes that he is the problem? In a restaurant during the denouement, Edward glances at a woman across the room wearing a tiny hat with netting draped over one eye. It feels significant, but goes nowhere, which is fine. He seems less passive and grateful for the people who want to be a part of his life, but the tragedy is that they have assigned an identity to him, and they do not know him. Edward seems different, but after such an emotional journey of high highs and low lows, it may feel like pulled punches. This film feels like “Dream Scenario” (2023) in the way that the protagonist comes to the too late realization of his bone deep inadequacies and lack of appreciation for his earlier life, which at least was authentic in its flaws. By having a character who defines himself through the woman that he thinks that he loves, Schimberg signals that vacuum of self-identity. The story embodies the unfulfilled promise and entitlement that a lot of ordinary men from the majority feel. At least it is not imitating “Flowers for Algernon” (1966) because Edward must live with the consequences of his decisions and actions after a sci-fi makeover.

If “A Different Man” has a fatal flaw, it is Schimberg’s proclivity to take huge narrative leaps to get his character where he wants sooner without enough connective tissue, and it can take a person out of suspension of disbelief because these transitions are so abrupt. It makes for funny material because of these fantastic flights into the absurd. For example, in the twenty-first century, it is hard to imagine a person reinventing himself without considering the logistics. Schimberg does a nice job throughout the film of weaving themes throughout: Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye,” the same outspoken raving man, the bartender, the super. It creates a satisfying chorus and reprise that reflects a lot about Edward’s inner life without heavy-handed prose dumping.

It is intriguing that “A Different Man” is out at the same time as “The Substance” (2024). Unlike “The Substance,” Schimberg’s film is not a horror though it shares body horror moments and the adage that being a slave to looks, even under objectively challenging circumstances, will ruin a person’s life regardless of how obscure the person is. Schimberg has the advantage in one crucial way, the (one-sided) war of the doppelgängers eventually gets abandoned, and it sticks to bringing Edward and Oswald together more.

“A Different Man” also feels like the anti-“Ghostlight” (2024). In “Ghostlight,” an amateur actor finds healing and connection through acting whereas Edward unravels in the spotlight and is worse off. There is this undercurrent threat to embracing creativity and judged lacking or succeeding, but it is a sham. While Oswald is a better actor and people person in comparison to Edward, it is unclear if he is a great under any circumstance. One of the greatest living American actors appears as himself in a terrific cameo, and Oswald wonders if he would measure up in a movie adaptation of Ingrid’s play. Um, yes, yes he would.

If Schimberg’s film is unique, it is for depicting people with disability as not inherently noble or deserving of everything. As his handsome alter-ego, Edward is dumb, possesses no emotional regulation and has nothing to offer. At least as the insecure, retiring earlier self, there was an air of mystery, and his simple pleasures were relatable like cooking while watching a video on a laptop.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

I loved that throughout “A Different Man,” people kept mistaking Edward for Oswald, but he does not know that, and no one ever figures it out or remarks on it. So technically even as his original self, the good will that Edward received stemmed from Oswald’s life. It is also interesting to note that Ingrid never invited Edward into her home until he became handsome, but it also made him disposable whereas Oswald got in and stayed in.