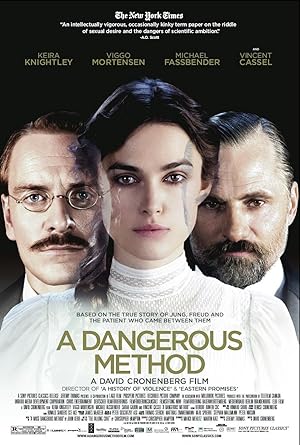

David Cronenberg directed A Dangerous Method, which is an adaptation of a play, The Talking Cure, which is in turn an adaptation of a book, A Dangerous Method: The story of Jung, Freud, and Sabina Spierlein, which I now have a moderate interest in reading. The film stars Michael Fassbender as Jung as he treats his patient, Spierlein played by Keira Knightley, but Viggo Mortensen transforms into Freud and steals the show.

A Dangerous Method appears late in Cronenberg’s career after he departed from his body horror roots and began to explore issues of identity in psychological thrillers. This film is a departure for Cronenberg even in comparison to his later work because it is a period piece, biopic, not fiction. Perhaps it is more due to accidental juxtaposition, but A Dangerous Method felt like the unofficial sequel to Scanners, which also has a three-point conflict in which one of the parties initially seems aligned with the other, but stands for something altogether different from the other two.

Spierlein is Vale, a former madman who is unafraid of erasing traditional boundaries of identity and takes the work of her predecessors to a level neither of them can imagine. Jung (and Gross) can be characterized as a more peaceful Revok who take the work of their intellectual father, Freud, who would be Dr. Paul Ruth, and transform it into something that is more psychologically violent and threatens to destroy the field, but lack an ability to reflect on the rationalization and morality of their impulses. A Dangerous Method seems to suggest that as a woman, Spierlein is particularly suited to surpass her fathers and by nature of her physicality, she has a biological advantage in psychoanalysis when it comes to her perspectives on sex and unearthing unconscious drives.

A Dangerous Method also feels like an unintended prequel to Maps to the Stars. In both films, the psychoanalyst seems more damaged and repressed than his patient. Instead of healing those around him, the psychologist threatens to exploit and injure his patients and others around him for hiding his unconscious compulsions behind his professional status in order to protect himself from consequences. Jung is like an early Stafford and without Freud’s intervention on behalf of Spierlein and his desire to keep up appearances as a proper husband and father, would become as monstrous. They both end up paralyzed beside bodies of water.

Even though Jung is the main character of A Dangerous Method, he is certainly not the hero of the movie. He betrays and exploits Spierlein, and Freud always seems suspicious of him. The emblematic scene that represents Jung is how he takes a disproportionate amount of food off the serving platter carelessly oblivious to anyone in the room other than Freud. Meanwhile the dinner table is overflowing with Freud’s family. Later on, Jung enjoys flaunting his financial advantage over Freud and his professional advantage over Spierlein. Jung’s wife is his sugar mama. Everyone must serve Jung’s appetites and when they do not fit in perfectly with his desires, even if they do not resist, he rejects them.

For me, Freud was the most interesting character in A Dangerous Method. He is implicitly offended by Jung’s greediness and carelessness, but sees it as characteristic of a larger problem of initially unconscious, but unapologetic privilege. Freud’s identity is rooted not in his intellectual legacy, though he guards it faithfully, but as a Jewish man facing prejudice, which explains his allegiance to and willingness to be more frank with Spierlein. It also does not hurt that for the first time, Fassbender seems like an amateur next to Mortensen, who disappears into his character. Mortensen may not appear often, but his appearances feel real and relatable. I wanted the film to be about Freud instead. It is an interesting piece of trivia that Fassbender and Mortensen share the same age difference as Jung and Freud.

A Dangerous Method is an interesting film to see before Wonder Woman since Cronenberg’s film is set before World War I, and Jung unknowingly suffers from debilitating visions of the impending wars, which is ironic considering that he is the only one of his colleagues who did not suffer from its devastation. One could conclude that without these wars, Jung may not have been as successful as he was because his competition literally died as a result of these wars-indirectly or directly.

A Dangerous Method is not one of my Cronenberg favorites. Knightley was miscast and did not disappear in her role though she clearly worked hard. Cronenberg failed to convey the passage of time or the break between the two men. Freud and Jung never seemed closed to me. If Cronenberg intended to depict a great relationship as it gradually then suddenly deteriorates, he failed. The deliberate pacing failed to hold my attention, and it felt strangely anemic. I think that A Dangerous Method is a solid film, but not a particularly enjoyable one; however I would recommend it to anyone interested in Cronenberg or Mortensen’s films or any of the historical figures depicted in the film.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.