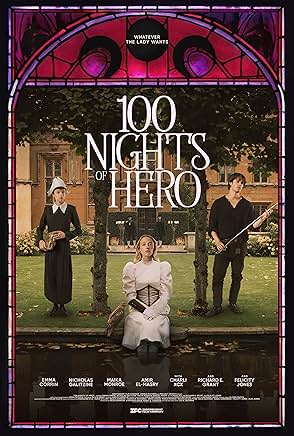

If Cherry (Maika Monroe), the ideal wife, is not pregnant in one hundred one nights, she will be put to death, but it takes two to make a baby, and her husband, Jerome (Amir El-Masry), leaves for “business” for one hundred nights. To further complicate things, Jerome bets that his homeless, handsome buddy, Manfred (Nicholas Galitzine), cannot seduce his virtuous wife while he goes away, but Manfred is motivated, needs to win and is the first heterosexual man of the right station left alone with Cherry and interested in her. Well, not exactly alone. The castle is filled with masked guards and servants, which includes Cherry’s best friend and maid, Hero (Emma Corrin), who regales them with stories to keep Cherry from falling for Manfred’s charms. Only one problem: women are not supposed to read or write, aka have knowledge. Will Cherry choose the right path? “100 Nights of Hero” adapts Isabel Greenberg’s graphic novel, “The One Hundred Nights of Hero,” which “One Thousand and One Nights” inspired. Director Julia Jackman’s second feature film and first-time writing is a comparatively light, lush, queer, feminist, fantasy film that tells a valuable lesson, and the parallels with this world make the slight changes seem more fanciful than necessary to further the story.

“100 Nights of Hero” is a veritable Russian nesting doll of stories with the same purpose. The original framing story involves Agnes (Markella Kavenagh) wishing for a better life for her future child, especially if the baby is a girl. The main story revolves around Cherry’s predicament. Cherry’s name is a bit on the nose considering her virginal status. Monroe had a wonderful streak playing bad ass women, but here she goes against type as a woman placed in a Kobayashi Maru situation. Cherry is an enthusiastic participant in her own destruction, not trying to subvert the status quo. She wants to do her wifely duty, but her husband will not let her. She cannot defend herself and tell the truth about her chaste marriage otherwise she would be exposing her husband. Even though Manfred is obviously inappropriate, and she should shun him, she must be a good hostess and entertain her husband’s friend. She uses the request for a story from Hero like a safe word to keep Manfred at arm’s length. She becomes the center of a love triangle that she barely understands since duty requires that she have no knowledge. Forget a double bind. She is in a multi-ply bind.

At the head of the love triangle is Hero. As the titular character, she has a tight rope to walk. She is clearly more erudite and a fully realized person than anyone else in “100 Nights of Hero,” but she also is a servant though she is never treated as such. Being a servant gives her leeway to act in ways that Cherry cannot. She has a graceful, forceful way of countering the status quo through art. Her androgyny signals that she does not obey the gender norms. Hero is entranced reading a secret story, which continues the opening tale of Agnes. Her stories are an antidote to societal ills such as misogyny, compulsive heteronormativity and anti-intellectualism. When these stories become more related to the established tales of that time, religious texts warning against heretical behavior with origins in history, her power begins to wane, which is the raison d’etre for this movie disguising religion with Birdman (Richard E. Grant) as the god who establishes the oppressive rigid rules. Stories have more power if you must work a little to get the message. The stories also function as Hero trying to argue her case to Cherry to not fall for Manfred and the fictional trap of conventional romance.

It is a tall order because even knowing that Manfred is a bad guy, Galitzine makes the rakish himbo into an irresistible temptation. Galitzine is not subtle whether he is walking around shirtless covered in blood from the hunt or feeding fruit to Cherry. He is fun but flawed. He is a man of the flesh who wants everything, to have the cake and eat it too, which means Cherry transforms into a convenient conquest to a person that he wants as his wife, which should not be conflated with caring about her reputation or well-being. He wants to bed her but figure out how to make it work. He is a villain who does not think that he is. Jackman emphasizes how he only relates to the man in Hero’s story but fundamentally cannot stray from Birdman’s teachings.

The love triangle feels like the point of “100 Nights of Hero,” but in the eleventh hour, the movie feels like a car that figures out at the last minute that the exit is approaching. It gets back on track to the double bind that women face in the form of Cherry’s guarantee that she will lose if she has an affair, and she will lose if her husband does not make her pregnant the second that he comes home. It gets back to the central message: women being demonized for innocent acts, punished for men’s shortcomings, and seeking refuge in the solidarity among women in the face of danger, themes that also appear in Hero’s story. It also reveals the tragic spiritual exile between men and women even if they want to be together because the values that they were raised with keeps them apart regardless of their desires. Men are also harmed in these stories because their power denies them love and true companionship.

“100 Nights of Hero” would have been better if the elements of the story were blended more thoroughly or at least each story has an equal amount of screen time. The rich mythology provides an excellent backdrop, but it would have been nice if it was more relevant than at the bookends of the film. As it is, a lot is left to the imagination in favor of the romance storyline. The original framing story feels cursory as opposed to a mic drop when all the threads come together. Stay for the post credit scene, which is amusing, but not essential to the film’s integrity. Apparently, there is some stunt casting with Charli XCX as a character in Hero’s story, but no disrespect intended, I don’t know her. Also, the film’s overall optimism about the masses and women’s allegiance to each other is a lovely sentiment, but sadly not reflected in reality. In the real world, Cherry is establishment and is unlikely to change.

Jackman’s film is gorgeous. Cinematographer Xenia Patricia and costume designer Susie Coulthard make it feel like a film set in an alternate past. Production designer Sofia Sacomani and set director Tatyana Jinto Rutherston make every scene seem luxurious and detailed. Editors Oona Flaherty and Amélie Labrèche reflect the disorienting effect that Hero’s story has on its listeners. The nights are marked with handwritten dashes, but it was more visually disruptive and distracting than intended since it flashes so quickly, it is almost not noticeable or impossible to count before they flash off screen.

“100 Nights of Hero” is a sweet, surprise of a love story with a simplistic, idealized hope for counter messaging against harmful power structures. It is so slight that the romance angle will outlast its attempt at proposing a delicate, peaceful, stylized revolution in any moviegoers’ mind so takeaway lessons may evaporate once the credits roll.