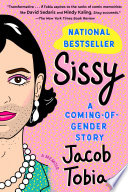

I heard about Sissy: A Coming-of-Gender Story at the same time that I heard of Jacob Tobia. Tobia was promoting their book on The Daily Show, and I liked them instantly so I requested the book from the library. I was going to pick it up, but then the pandemic happened so I would not be able to get it until months later. Up until then, I was not enjoying anything that I was reading and thought that perhaps I finally lost my ability to concentrate and derive pleasure from reading. While it is still incredibly difficult to find a stretch of uninterrupted time to read, I am pleased to report that it was the books’ fault, not me, because I loved reading Tobia’s book.

Tobia’s voice reflects their personality-fun, fresh and thoughtful. Even though I read Sissy: A Coming-of-Gender Story to learn more about Tobia’s story, I also think that it is more like the book that Eddie Izzard set out to write Believe Me: A Memoir of Love, Death, and Jazz Chickens. It could simply be cultural and generational differences that makes Tobia’s story riveting, dynamic and incidentally educational and Izzard’s book self-indulgent, circuitous and baffling. Izzard comes from the United Kingdom, a land of colonizers so Izzard looked around and in order to carve a space for himself, took what he needed to survive. I love him, but his approach ignored today’s cultural context, which makes sense if you were lived in a world where you are seemingly the first. Tobia is conscious, but not self-conscious of their place in this particular point in time by looking back and forward to describe where they are now. So I left Tobia’s book learning that trans stories can be nonbinary, genderqueer without inadvertently invalidating others stories and explicitly acknowledging the world that preceded their story.

Sissy: A Coming-of-Gender Story seamlessly mixes memoir with instruction without being pedantic. Tobia often compares and contrasts what they wished happened with what actually happened. I feel as if everyone should read this book because it is a great book, but especially anyone who frequently interacts with kids: teachers, parents, uncles, aunts, older kids. Tobia is fiercely upbeat, but even they had no respite from the nonstop bullying at home. If people say that they do not care what other people do as long as it is behind closed doors in their own home, Tobia is here to say, “Actually you do.” The reinforcement of gender norms is so pervasive and omnipresent that for someone who is cis, it can be unimaginable how torturous it is to constantly be corrected for deviating in the slightest. I feel fortunate that even though I was born fundamentalist, I was raised in New York during the seventies and eighties so the cultural styles were inherently androgynous so wearing a man’s shirt and tie was a fashion statement, not rebuked. As a cis professional woman, because there is an implied expectation that I will be in male, professional drag, it is more radical to explore feminine norms within that context: brighter colors, long dresses, lots of jewelry. When not thinking, grays and blacks in athletic wear is my speed, but I was surprised when I could wear fuchsia or teal without feeling uncomfortable. When I was a child, dressing up like a girly girl felt like the proper offset and cover to the not girly girl things that I was doing (building toys, physically fighting back when bullied). I was given a complete spectrum, and the idea that anyone cannot have the same privilege to explore, which costs nothing, is infuriating.

While I went into reading Sissy: A Coming-of-Gender Story expecting to like Tobia, I did not anticipate relating to them so much. Even though our journeys are incredibly different, their gender journey and my race and gender intersectional journeys have similar trajectories: the counterintuitive refuge of church and academic accomplishment with the eventual disillusionment and necessary recalibration with both. To be fair, it took Tobia far less time to have the epiphanies that they details in their book than I did, and once they did, seemingly had less self-doubt about where the blame lie in every situation, but it definitely suggestions that the hate tree may have different branches, but it springs from the same route so it should not be surprising that when we try to deflect this tree trying to trip us up, the route looks similar.

The Beloved Token chapter in Sissy: A Coming-of-Gender Story makes the distinction between succeeding in spite of versus succeeding because of one’s surroundings. It is a double-edged sword. Our accomplishments and existence incorrectly indemnify unjust organizations that are not actually making a space for us by not explicitly denying us entrance or dragging us out. When we allow that tolerance to deceive us into incorrectly believing that we are actually being celebrated and divides us from those similar to ourselves by patting ourselves on the back as better than them or special, it is the latter that makes us vulnerable and alone. I had that mantle placed upon me, immediately discovered that it did not fit and shook it off, but it was only when I openly challenged that dynamic that I lost my status as magical Negro, the spot of diversity at every promotional event while behind closed doors, relegated to the borders. Even if I was not consciously rejecting it, everyone else got the message. I call it the black wake up call when someone tries to pretend that you’re not like “them,” and you push back by not cosigning problematic behavior, “I am not your black friend.” A lot of Presidon’t, particularly black male, supporters are going to find out the hard way that the benefits are transitory. Proverbs 14:12, “There is a way which seemeth right unto a man, but the end thereof are the ways of death.” Right, Herman Cain.

Tobia is able to capture these experiences so perfectly because of their emotional intelligence and ability to recall what they felt in the past, specifically, “[T]he only reason you are succeeding in the first place is because you have so dissociated from your own emotions that you no longer feel the sting of daily hostility.” Tobia describes a childhood where the rage that should have been directed at those who hurt them was directed at the aspects of themselves that they loved. I do not think that we ever outgrow this impulse to commit “spiritual murder” or suicide. Tobia gets stronger when they unashamedly direct that anger outwardly naming the way others are erasing. Tobia provides an alternative solution to society’s rebuke to remain unemotional, to let go of hurt, to get over it. “I will never get over the fact that people have been terrible to me because of who I am….And I won’t forget it because I, along with every other oppressed person on the planet, am owed. Society has a debt to me—to all of us—one they will likely never repay. I want the things that have been taken from me. I want them back.”

In Sissy: A Coming-of-Gender Story, Tobia expresses what I have not even said aloud the quotidian parts of life that I want for myself because I do not think that I will get them because of my difference. I encourage you to read this book because it may make you give life to the parts that you were unaware that you smothered to survive.