I read Shusaku Endo’s Silence: A Novel after seeing Silence and Chinmoku. Silence is a more faithful adaptation than Chinmoku, the first adaptation, but I prefer Chinmoku to Silence; however both adaptations miss several key points that Silence: A Novel makes.

First, Silence: A Novel shifts from the subjective perspective of the author of the letters, which is depicted in Silence, but also uses the omniscient narrator observing the characters objectively. Neither film effectively depicts this shifting perspective effectively, and I actually think that it is a flaw in Silence: A Novel because there are times when the transition from a letter to narration is unclear. It is possible that something got lost in translation or in the edition that I read, but it is a problem nevertheless because the perspective switch reveals my second point.

Second, Silence: A Novel depicts Sebastian Rodrigues as innately psychologically different from his fellow missionary, Garrpe, particularly in his mental visual association of Jesus and Ferreira and the difference in their priorities. Garrpe wants to preach the Gospel, but Rodrigues wants to find Ferreira and preach the Gospel. I think that Chinmoku implicitly suggests the problematic nature of Rodrigues’ relationship with Ferreira, but does not quite capture the source of that problem. Chinmoku makes the persecution seem artful-eliminate one partner then substitute another who is a corrupting influence to destroy the “where two or more are gathered” dynamic of Garrpe and Rodrigues. Whereas Silence makes their relationship seem like the only solace both men have in a lifetime of imprisonment and surveillance. Both film adaptations miss the mark. The problem for Rodrigues is one of idolatry, a conflation of Jesus and Ferreira with a secret prideful aspiration to be like them. He is more interested in reality as he perceives it, but Silence: A Novel constantly shows how Rodrigues’ assessment of his environment is always wrong. He is an unreliable narrator and more paternalistic, less likeable than both films make him.

Third, only Silence: A Novel effectively explains the concept of Japan as a swamp. I drew the conclusion, perhaps incorrectly, that Silence: A Novel suggests that Buddhism is better suited to Japan because it allows for human weakness whereas Christianity requires inner strength. I am not suggesting that Buddhism actually does that because I know very little to nothing about Buddhism, but I do not think that is a fair characterization of Christianity although I can see how someone would assert that. I think that this aspect of Silence: A Novel is possibly more specific to Endo’s struggle with his nation and his faith than necessarily an accurate assessment of Christianity and Japan based on the few critiques that I read of his work. Weakness in the face of suffering and reputation within the Christian community is more important in my reading of Silence: A Novel than the idea that most people find provocative: can you still be a Christian and openly apostatize? I think that it is interesting that Endo never explicitly alludes to Peter, but he does mention cocks crowing.

Without the film adaptations, I do not think that Silence: A Novel would have gotten my attention, but I am glad that I read it. If you found the films interesting, I think that it is essential reading, but if the subject matter leaves you cold, then run. I do not think that watching the films first will spoil your reading experience. It is one of the rare times that I prefer a film, Chinmoku, over the book, Silence: A Novel.

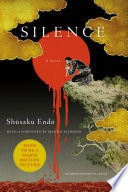

Silence: A Novel

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.