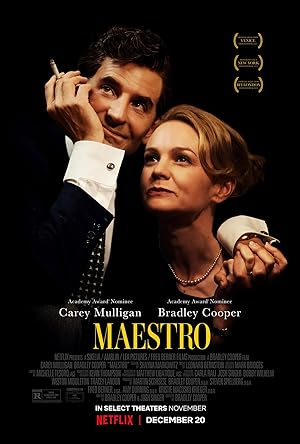

“Maestro” (2023) is actor, director and cowriter Bradley Cooper’s sophomore film, a biopic about conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein (Bradley Cooper) starting at the height of his fame and his relationship with his wife, actor Felicia Montealegre Cohn Bernstein (Carey Mulligan). It is divided into two parts, black and white at the beginning of their relationship and their careers and in color as their relationship is ending.

Quick recap: Cooper was impossible to dismiss as an acting pretty boy, dime-a-dozen actor after his stunning directorial debut in “A Star Is Born” (2018), which reflected a deep respect for the film’s history, featured seamless acting and musical performances, and infused autobiographical details about Cooper without destroying the cohesion and artistic integrity of the original story. Movies about the crossroads between love and art drawing two people together makes “Maestro” a natural successor. Bernstein appears as a shooting star when he courts understudy Felicia who ascends to the lead. The energy from their professional success is contrasted with the calm and peace that they find with each other in their quiet moments. They are each other’s biggest cheerleaders with Felicia urging Bernstein not to hide his Jewishness and believing in his musical genius. Too bad that these early scenes feel too stylistic, and as if they are acting, not like the genuine rapturous moments of true love at first sight captured in Baz Luhrmann’s “Romeo + Juliet” (1996).

Cooper’s first half feels like an acting and directing exercise where he aims for Todd Haynes’ crown as a man capable of making a film that feels as if it was made during the era of its setting. “Maestro” is a technical marvel with sweeping tracking shots that encompass entire buildings with invisible transitions that leap forward in time and space to convey the rapid, transforming ascent of fame. Orson Welles is watching from the grave with approval. The camera and lighting convey the emotion, not the actors. A lot of people made a big deal about Cooper’s prosthetic nose, but the Internet failed to describe how horrific the death mask of makeup that Cooper wears in the black and white scenes in the first half appear. It makes a gorgeous man look grotesque as he tries to capture the youth and vigor of early Bernstein. His face looks rigid and lifeless as if a slew of plastic surgeons attacked him with syringes filled with Botox or a remix of “The Twilight Zone” episode “The Masks.”

While trying to evoke the rapid-fire patter of conversation from classic cinema, Cooper makes the first half of the story unintelligible if viewers watch it without the benefits of closed captioning or already possessing an encyclopedic, detailed knowledge of these people. The clueless will remain so after a first viewing as the film goes on moments of montage whimsy to summarize Bernstein’s work with an extended allusion to “On the Town” (1949) where Cooper decides to give choreography a try. The sequence is about the lives that Bernstein and Felicia want together professionally and personally and the existing temptations which have the potential to tear them apart. The musical interlude reemerges later in the film during times of discord. Even a versatile, engaging, committed actor like Cooper should know his limits. He is not a young man or a dancer, and it gets a bit awkward. The flip side of his earnest and sincere attempt at embodying the letter and spirit of Bernstein is being a self, indulgent ham who would rather wear all the hats than create a grounded portrait of an icon and delegate some of the work to others, i.e. a younger actor who looks like Bernstein.

Viewers with an innate trust in Cooper’s nerdy devotion to film and music history will have patience and make it to the stronger, more digestible second half, but if you cannot muddle through, fast forward until you see color. In color, the mask of youth appears less disturbing, and Cooper’s acting gradually disappears until he becomes Bernstein. Cooper’s makeup as the older Bernstein works best. As fat and wrinkles get added to the get up, the more organic the acting. The film gradually reduces the manic, cocktail party perpetual motion vibe and switches to a more grounded Felicia, who is living in her husband’s shadow and distressed at his infidelity while Bernstein lives a life separate from his family, unable to deny his desires—he prefers men sexually.

I have an automatic bias when straight men play men who are not, which I did not bring to “Maestro” because I never thought about Bernstein’s sexuality though in retrospect, a musical about sailors on leave in Manhattan was a dead giveaway. Duh! An added complexity is Cooper wants the Bernstein family’s blessing, but who wants to think about their father’s sexuality or can view it dispassionately or objectively. If sexuality is going to be pivotal to a story, then filmmakers need to clearly convey information: the attitude of the time privately and publicly (it was illegal to be gay but gay people have always existed and with enough privilege, money, and fame, gay people could live the life that they wanted without fear of repercussion). Is Bernstein gay or bi? Is Bernstein gay and Felicia is a willing, informed consent beard or a one-off exception? Did she know before and was cool with it, did she not know, did she think that she was cool with it then was not? What changed? The film is coy, but the film appears to be saying that Felicia accepted and knew but thought she would occupy a bigger space in his life, and as it shrunk, she could not tolerate it. On the other hand, the dialogue in the Thanksgiving blowup between the couple suggests that she is sick of his pretense and veiled anger at hiding his true self or is there some projection? It is a muddled domestic drama, but Mulligan ends up winning as the captivating actor with Snoopy coming in second.

Mulligan’s face projects the transformation of Felicia’s emotions from frustration, anger, anxious, loneliness, resignation, admiration, and fear. Her character goes on a complete journey throughout “Maestro,” and by the end, as her body hijacks her ability to function throughout the world in the light, keeping up appearances way that she could before, Mulligan’s performance and Cooper’s direction conveys how death destroys her ability to maintain pretense and social niceties. By the time that Bernstein and Felicia figure out that they are happier and more functional as a pair even if they cannot complete each other, time is up.

Will “Maestro” help you understand Bernstein? Nope! The whole movie seems more of a reflection of Cooper’s latest fanboy cosplay. Cooper introduces themes but fails to explore them consistently. The dual nature of Bernstein is constantly alluded to with parallels to a public and private persona: conductor and composer, married man, and adulterer, heterosexual and gay. The dialogue suggests that this duality makes him the talented man that he is but telling versus showing/feeling are two different things. Recreated interviews with Bernstein signal a shift and orient viewers regarding what we should look for. The film opens with the oldest version of Bernstein discussing the importance of his wife. During the full bloom of their relationship, an interview with his wife while his daughter and housekeeper watch on in the wings signal his perfect public persona. A solo recorded interview for a book presages doom, “World on verge of collapse.” Spoiler alert: substitute family life for the world. The final interview is a kind of a happy ending-he misses his wife, but he can finally live the life that he wants without making others angry.

If you start watching “Maestro” to revel in the unintended camp and over the topness, you can start to have fun. Let the old man go clubbing! Cooper’s voice in the second half and outfits send me over the moon: the cable knit sweater, the horizontal stripe long sleeve T, the track suits with the silver platter. Architecture, interiors, swoon! Love! It is all very superficial, but a movie can soar on style even if you leave hungry for substance—“Saltburn” (2023)! If Cooper had just aimed for flamboyant and fun and stayed the course, the movie could have worked. The film seemed vaguely embarrassed at how Bernstein balanced his life, and it is deeply inappropriate to tell a baby that he slept with both their parents, but if that man is the real thing, then embrace it and become as unashamed and amoral as Karen in Will and Grace. Let everyone have fun being a bad boy, not sudden finger wagging when he is at his most sedate hedonistic level. Cooper does show genuine emotion as Bernstein when Bernstein focuses on sacrifice and steps up as a devoted husband and father, but The Blue Caftan (2022) does it better without the flashiness and with more sincerity. There is plenty room for improvement.

“Maestro” is a mess, but it is an artistic mess. Cooper is a walking red flag with two films that idolize women who forgo living the full life that every human being deserves and sacrifice their artistic talent and life in service to acting as the emotional foundation for a great man. Yikes! I’m choosing to see this flag as a parade, not a warning, and will be back for Cooper’s next pursuit even if it is as shallow and misguided as this one.