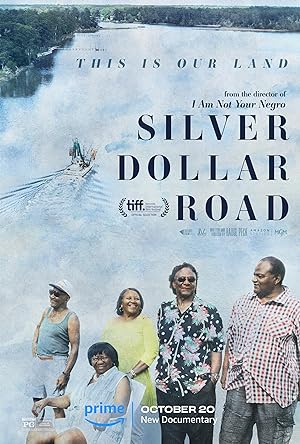

“Silver Dollar Road” (2023) refers to a street in a North Carolina seafront neighborhood that the Reels family has owned and lived in since emancipation. Haitian director Raoul Peck’s latest documentary pays tribute to the family, their history, and their fight to retain that land despite facing enormous legal obstacles. It is a feature adaptation of ProPublica journalist Lizzy Presser’s article “Their Family Bought Land One Generation After Slavery. The Reels Brothers Spent Eight Years in Jail for Refusing to Leave It,” which was published on July 15, 2019 in collaboration with The New Yorker. Peck’s film contains excerpts from two years of footage from ProPublica’s Directors of Photography Mayeta Clark and Katie Campbell. Most directors would view the Reels family’s story as a legal drama, but Peck rejects the instinctual choice and mostly omits the talking heads and legal analysis in favor of prioritizing the family members and how they experienced life on their land and in our legal system.

Echoing the choice of the second Black owner of the land, patriarch Mitchell Reels, Peck casts three generations of Reels women as the documentary’s successive stars who pass the baton of protecting the family, their way of life and property, which Elijah Reels, Mitchell Reels’ father, purchased in November 1911. Starting with ninety-five-year-old Gertrude Reels, the matriarch and property administrator, she recounts how her father charged her with the responsibility of protecting the property, which secured the family’s way of life, because he correctly had faith that she would honor his final wishes. Mamie Ellison, Gertrude’s daughter, continues in her mother’s footsteps—a considerable personal sacrifice. New Orleans native Kim Duhon, Gertrude’s granddaughter, and Mamie’s niece, eventually moved to the area and visited her uncles, Melvin Davis and Licurtis Reels, weekly during their eight-year civil incarceration and tirelessly worked on finding a lawyer. Other Reels family members share the spotlight to regale the camera with bucolic family stories dating back to antebellum times; thus, preserving their stories for as long as this film exists and is circulating.

To get screentime in “Silver Dollar Road,” you must be a family member or on the family’s side. There is archival news footage of journalists covering the story and interviews with two lawyers, Anita Earls, who represented the Reels from 2006 through 2007, and James Hairston, who succeeded in getting the Court to release Melvin and Licurtis. Peck gets Hairston to explain less punitive legal remedies that the Court could have ordered instead of incarceration. When Earls suggests that this case is too complex for the family or even most legal professionals to understand, one should not equate her statement with Earls and Peck being incapable to convey that information to laymen viewers. At the time of filming, Earls is a North Carolina Supreme Court Justice who probably knows the case like the back of her hand. Peck is internationally educated and served as Haitian Minister of Culture.

“Silver Dollar Road” does not devote substantial time to legal analysis because Peck chooses not to tell that story. The implication is that Peck associates the US justice system and law enforcement with Mamie’s statements which suggest that the legal game is rigged, “That’s how they get what they get by lying….stealing, killing and ku klux klanning all their life,” The dismissive stance is harsh, but earned considering the court confirmed the Reels’ ownership in 1976 yet appears to subsequently reverse itself at the behest of gentrifying developers. Peck elects not to perpetuate what he perceives as other people’s lying narrative within his film and refuses to turn the Reels into supporting characters in their own story by diverting focus on their opponents. The alleged devil, Adams Creek Associates, has enough advocates and allies. Other attorneys used the family like a walking, talking ATM without offering much in return.

If an outsider is against the family’s interest, to get featured in “Silver Dollar Road,” a family member will have to deem that person germane to the proceedings and memorialize your presence as Mamie did in May 2011. Mamie’s handheld, trembling recording captures a group of unidentified white men carrying tools and other men dressed in sheriff uniforms with their hands near their hip hovering over their seemingly unholstered guns. Mamie’s amateur recording is visually inscrutable and requires Dramamine to digest but has the power to convey heightened emotion like chaos cinema. Mamie urges Billy, her son, to not interact with them. Unlike his earlier films, Peck does not remind contemporary viewers of the broader context of potential physical violence or extrajudicial execution, the underlying subtextual threat of this encounter. It is unnecessary and would be redundant given the footage. Instead, Peck’s film is a rigorous antidote to the prevalent images of black pain and suffering. His utopian trajectory is aiming for heaven on earth and centralizing how this waterfront property functioned as a rare paradise for Black people.

“Silver Dollar Road” begins with a written exchange between General Tecumseh Sherman and South Carolina Reverend Garrison Frazier. Sherman asked what former enslaved people would need to survive emancipation. Frazier responded, “The way we can best take care of ourselves is to have land and turn it and till it by our own labor.” Peck contextualizes the Reels’ property as a microcosm to a broader national context dating back to the nineteenth century. This legal battle is the latest, twenty-first century battleground for the Civil War, and the key to freedom is conflated with land ownership. To conceive of contemporary freedom from oppression in the present, think of a world without stop and frisk, monitoring, state authorized violence and microaggressions.

Peck visually associates that freedom with overhead, sweeping shots of the land and depict what life looks like in a world where Black people own the land —a quotidian, American, humble Wakandan paradise. There are entire sequences devoted to members recalling their childhoods, showing children gathering without fear, casual family gatherings. Peck paints an image of Black quotidian life free of hostile observation and interference that only comes with widespread land ownership. Peck does offer glimpses of former prospering Black communities now lost. Neighborhoods that displace Black communities coincidentally sport Confederate monuments. Peck is invested in a wholesome family because if they fail, the impact leads to an ahistorical, supremacist makeover.

If “Silver Dollar Road” is propaganda, it is subtle because Peck does not make the overt analogy that can be drawn from this case. The Reels act as a microcosm for Black people, but also serve as a broader warning for small property owners, small business purveyors and ordinary people of any race. Anyone can legally lose their property, including their business, and get incarcerated if a bigger player has the resources because justice requires big pockets. Race exacerbates the situation, but it is only one branch on a twisted tree of hate. Property and businesses are abstract concepts. Peck personifies the land by treating the family members as part of the natural landscape with illustrations of their family tree, which resonates more. This verdant theme later echoes in animation depicting the brothers’ time in a desolate, isolated, cold, enclosed space. The trees’ vines/branches invade the cell and touch them—incarceration cannot disrupt their solid connection to the family and land. Keep tissues on hand for Melvin and Licurtis’ release and reunion with their family, which includes security footage before they see their family.

Peck moves in a countercultural direction, which should be no surprise for fans of his notable, genre-defying documentary “I Am Not Your Negro” (2016), which examined how colonizing narratives are violent and monstrous for condemning instinctual human emotional responses to oppression.