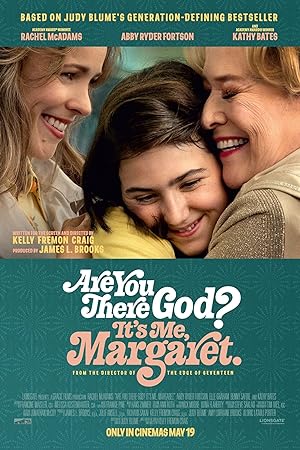

“Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.” (2023) is author Judy Bloom’s authorized adaptation, which she describes as better than the book. Starting in 1970, the titular prepubescent teen (Abby Ryder Fortson, who proves that the best revenge is living well after MCU recast her most famous role prior to this one, Ant-Man’s daughter, Cassie) moves with her family from Manhattan and adjusts to life in the New Jersey suburbs. She starts praying to become a woman. Meanwhile her mom, Barbara Simon (Rachel McAdams, and paternal grandmother, Sylvia (Kathy Bates), struggle with their respective identities.

I was into Blume’s books when I was a kid with complete freedom of access to my local New York Public Library branch, but that was a long time ago, and I only remember a few details. Don’t expect a comparison of the book and the movie. I went into the movie with some trepidation because a prepubescent protagonist can only appeal to nostalgia for so long. Good news for any adults accompanying children: you will be just as charmed.

Barbara, Sylvia and dad Herb (Benny Safdie, yes one of the brother directing duo known for “Uncut Gems”) were interesting individual characters without pro se dumps. The dialogue and acting felt organic and showed a lot about the characters without telling the audience about the characters.

I did not expect to have a story about three generations of women experiencing an identity crisis. Upon arriving in New Jersey, after Nancy Wheeler (Elle Graham) recruits her to a secret club, Margaret is having a spiritual crisis and is insecure about her potential to become a woman as if one can earn womanhood. Margaret’s crisis reaped the most laughs as she chants “I must increase my bust” and got excited to get her period (it’s a trap). She also learns about the perils of trying to measure up to being a woman and never winning. She feels inadequate for not achieving certain milestones, but when Laura Danker (Isol Young) appears to reach those markers, Margaret and her friends shun Laura. Margaret’s coming age story is about becoming a full person and not playing into image, a game that no one can win. Comparison is the thief of joy.

Barbara is having a similar crisis: self-imposed guilt about the woman that she is supposed to be as a mother and daughter. Sylvia defines herself based on her relationship to her family as a mother and grandmother and would not have experienced a crisis if her family had not moved. I related to her the most because of her aesthetic choices, revulsion at the idea of leaving Manhattan and moving to New Jersey and her reluctance to lift anything heavy. Even though there was tension between Barbara and Sylvia, neither falls into the dynamic of warring in laws.

“Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.” never villainizes its characters because director and writer Kelly Fremon Craig avoids pat tropes. It is easy to turn Nancy into the mean girl, but in an extended bathroom sequence, Craig depicts Nancy as she is: a frightened, little girl. Whenever Margaret or Laura gets something that Nancy wants, Craig includes shots of Graham’s earnest, hurt emotional reaction. Nancy believes that by bossing everyone around, she can manage an uncontrollable phenomenon.

Herb plays a small and pivotal role to ensure that viewers do not misinterpret Barbara or Sylvia’s struggles. He is the rare image of a perfect husband and father. Sylvia does not get framed as the meddling, monstrous mother-in-law, but a human being who cares for her granddaughter. When there is bad news, Herb insists on delivering it to his mother and protects his wife from being blamed for their decision. It is also easy to suspect that Herb has encouraged Barbara to abandon her passion and career as an art teacher to become a stay-at-home mom and wife and is isolating her, but Craig includes enough scenes to show that Barbara and Herb had this romantic idea of living in the suburbs that did not match their skills or identity. Throughout “Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.,” Barbara is trying to choose living room furniture, which is emblematic of her inability to express her identity, the one that she thinks that she should have versus who she is. When Herb comes home an empty living room, he improvs and delivers this great speech on contentment. This scene signifies that he is willing to give her space to figure out what she wants even if it affects him. He is not like many men who would critique her and ask, “What do you do all day?”

When Barbara has an issue with her parents that directly harms him, Herb expresses his pain, but is empathetic enough to stand with Barbara. Safdie does some amazing physical acting to show that he supports her and understands the conflict without resorting to ultimatums. He states both sides of the problem but decides that it affects Barbara more than him. If I was in his position, I do not think that I could do the same, but it is a masterclass in emotional intelligence and self-sacrifice without betraying one’s values. I also loved that as parents, Herb and Barbara encouraged all aspects of Margaret’s growing independence, including her crushes. Herb is a countercultural, but much needed example of images of masculinity. (What does he do for a living? No idea.)

Craig nails making a seventies period film. If you watch any old episodes of “Sesame Street,” “Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.” evokes a similar visual vibe from the casting, the wardrobe and furniture. Children of the 70’s can attest that the multicultural vibe of that region is authentic, but we did not know that everyone did not have that experience. There is a getting ready montage before a birthday party, and Craig shows Janie (Amari Alexis Price), one of Margaret’s friends, who happens to be black, getting her hair done: hot comb, wincing, mom telling her to sit still. Craig listened to the black people in her team! It was right up there with “How to Get Away with Murder” greatest moments in black hair. I peeped who Margaret ended up being besties with and interested in.

The holiday neighborhood montage reminded me of “The Fabelmans” (2022) although there was one house that had Hannukah and Christmas decorations versus the Simons’ absence of lights. The teacher is fortunate that he did not get in trouble for initiating an existential crisis for assigning religion as the protagonist’s yearlong project. Though the road to religious discovery should have resonated for me, it did not land until the huge confrontation scene when Margaret’s family treat her like property/an object, not a person, by claiming her for their side on the religious divide instead of treating her like a person with autonomy. “Why do I only feel you [God] when I’m alone?”