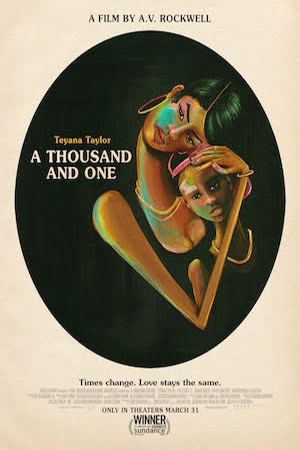

“A Thousand and One” (2003), a title that evokes the odds stacked against the characters or the chance to win the lottery of life, starts after Inez (Teyana Taylor) is readjusting to life after two years in Riker’s Island. She tries to reconnect with her son, six-year-old Terry (Aaron Kingsley Adetola), “T,” who is sulking and believes that she abandoned him. After T ends up in the hospital, Inez refuses to let T return to the foster home. They end up on the run. The film starts in 1994, jumps forward to 2001 and ends five years later. Even though Lena Waithe—“Queen & Slim” (2019)—is a producer, don’t worry. No one gets shot and dies.

“A Thousand and One” is not another sad black movie. If Kore-eda Hirokazu was assigned female at birth, black and a New Yorker with a love for classic Hollywood woman’s films such as “Stella Dallas” (1937) and “Mildred Pierce” (1945), then you can begin to understand A.V. Rockwell’s style. Even that description would not capture how Rockwell captures each time period and the vibrant primary colors of the nineties before the flat, cool, grey tones of commercialism and gentrification smothered it. Rockwell is a true filmmaker, not a prose dumper, who lets your eyes understand the story and the times.

Taylor belongs on the same level as Joan Crawford and Bette Davis. You will not be able to stop thinking about her performance as Inez, an inscrutable woman. Rockwell first shows Inez in a cell with another woman as serious about hairdressing as if she was a surgeon in an operating room. Inez does not just make things and people better, she makes them beautiful. When she gets out, her first stop is in front of an industrial roller shutter door, which shelters a closed beauty shop. She wants to get her last paycheck and job. Inez’s criminal history exiles her from ever returning to her true vocation. For the duration of “A Thousand and One,” she remains outside of the beauty shop’s doors. Undefeated, Inez darts in and out of traffic with bright yellow flyers advertising her skill, doing hair on stoops or in bathrooms. The real advertisement is Inez’s looks: straight, slicked back hair with curls of baby hair framing her ears, a thick, impeccable brow line and bold lined lip with thick false lashes and bulky gold hoops or door knocker earrings and her name in cursive emblazoned on a gold necklace. She is meticulous, highly stylized, and gorgeous. Even then she has a plan, doing hair on Brooklyn stoops while looking for Terry. Later Inez reveals that she feels more at home in Harlem.

“A Thousand and One” is the kind of film that you will want to rewatch. Taylor is a rare actor who can project multiple emotions in a second. Inez’s instinct is to lash out, but with T, she is at war with herself. She wants to be better for him so when he rejects a toy as “corny,” she acknowledges and accepts his judgment. She replies, “What you like?” as if to apologize for the distance between them. She tries to meet him where he is instead of (it is implied) mimicking the way that she was (not) raised—with rebuke for being ungrateful. In another scene, T messes up the living room after one day of being a latchkey kid. “This house looking….” before switching up and asking how he is doing. Taylor commits to that understanding-that T is doing the best that he can by obeying her orders, not going outside to play and attracting unwanted attention even if how he did it was not how she pictured it.

In contrast, there are two scenes where Inez lashes out, and Rockwell makes interesting choices in both. Inez relies on Kim (Terri Abney), her friend, a real one, for a place to stay, but Kim’s mother (Delissa Reynolds), a kind woman who treats T like her own, shows nothing but contempt to Inez. Reynolds chooses discretion and only allows the viewer to hear, not see, the altercation because she sympathizes with both women. Kim’s mother’s respectability politics may not be kind, but she remains sympathetic because she senses correctly that Inez and T will risk her security. Respectability politics keeps her safe, and Inez shows us how hard the world can be to those who make mistakes even though to err is human. Reynolds chooses to show the effect of Inez lashing out against Lucky (William Catlett), her love interest, the effect that it has on the kitchen and Lucky to emphasize Lucky’s reaction, a reflection of his character, which makes his subsequent actions more meaningful. Inez chooses gentleness for T, but it is not natural.

I loved Inez. Really pay attention to her appearance in each period. Still a beautiful woman, she pours all the energy that she put into herself and her vocation into her home and the people that she chooses to be in her life, T and Lucky, in each period. She transforms everything around her and makes a family. Without a lot of resources, Reynolds shows Inez making something out of nothing. Stoops, her place of business, can transform into playgrounds, reception halls for special occasions, or a public square to create community.

Inez can never just rest on her laurels and be secure in her accomplishments. Inez’s effort takes a toll, and her style of dress becomes more practical. She starts to cover her hair with a bandana. Taylor has this verging on unhinged scene. Reynolds just sets the camera on Taylor as she sits in bed alone watching “Ricki Lake,” crying and laughing, relating and elevating tabloid talk shows to a universal place of solidarity and strength. It is a moment of true cinema.

The tension in “A Thousand and One” is the question of whether Inez’s sacrifices will be for nothing, and if her family will survive the forces bigger than them: police brutality and gentrification. This film nails the inherent tension in the city for black people, but especially for someone like Inez who has kidnapped a child from foster care. Will she go to jail? Without being pedantic, Reynolds shows Harlem from above—the literal air waves—while playing news audio to orient viewers to the increasing danger of the Mayor Giuliani years with explicit reference to the NYPD’s rape of Abner Louima and murder of Guinean student Amadou Diallo. On the ground level, Reynolds reflects a Chantal Ackerman-esque, i.e. almost imperceptible shift, as stores close, people move and the neighborhood’s demographic shifts. If you are a New Yorker, you will see plot twists to undermine Inez’s accomplishments before they happen. I can watch horror movies without any dread, but it was unbearable to see the obstacles pile up. What is going to go wrong?

Three different actors play T for each period, and as he gets older, “A Thousand and One,” shifts to him. He becomes the focal point for everyone’s hopes and dreams, but there is also fear that there are other traps to avoid. I did not know that it is a felony to misrepresent your name and social security on college applications! Without mentioning Presidon’t—and Giuliani makes a great substitute, T’s inability to use his birth name and social security number may remind some of DACA without explicitly referencing them. Will the academically gifted T lose out on opportunities because he does not have the right identification. Inez and T are held to higher, more stringent standards than others around them (such as slumlords) who put them in jeopardy, but they get judged for being victimized too.

In a city where one can get incarcerated for jaywalking, Inez makes the choice to become a criminal by committing a revolutionary act: successfully raising a black boy in the US, loving a black man and having a black family. The best revenge is living well. Inez’s defiance and navigating the world on her terms makes her one of my favorite anti-heroes. Though “A Thousand and One” is melodramatic, and Inez’s experience is not representative of most women, her final speech could be the defiant cry of every black woman who survived and helped move the next generation forward, “I don’t give a fuck. Because I still won. I won! Because I know that you’re going to be somebody.” Even in the midst of her fierce love for T, she chooses herself first.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

I am not going to explicitly state the big twist in “A Thousand and One,” which is the number of the apartment that T and Inez live in, but when Inez reveals all her secrets, just when it appears that the slumlord and the law will defeat her, she is free to fight for herself again now that T is old enough to take care of himself and has people who are willing to take care of him. She is reborn. Her hair is done. She looks amazing. Her face is beat to the gods. She did win, and she is ready for another round! There should never be a sequel, but I want to know what happens. And by proxy, even as the black people are pushed out of Harlem, and she is on the run, unlike “In the Heights” (2021), there is a sense of triumph. We already saw what Inez did with nothing and a kid. She can do it again somewhere else. In this aspect, Inez and T’s experience is a microcosm of the indomitable nature of black people who cannot be eliminated even with an entire system pointed against us. Nothing can stop us even a stacked deck. She only stopped fighting and became compliant to get T to the finish line, but she can leave everything behind and start from scratch. It is unfair, but she is undefeated. It reminded me of Faye Dunaway’s boardroom scene in “Mommie Dearest” (1981) except she does not need to stay or anything. Harlem needs her. She does not need Harlem. She will make it work and rise elsewhere.

Also I did not mention Lucky, but wow, the theme of music in his relationship with T was really meaningful. Even though I did not want Inez to bring him into her home and thought he was a liability, all his scenes with T made me reconsider my earlier judgment. Under Inez’s love, he died a great man. Now I hate the idea of a woman having to drag people to greatness instead of just focusing on herself, but when she succeeds, I’ll sign a waiver.

I loved the little moments—all the black women who helped her get closer to victory: Kim and her mom, the landlady (Adriane Lenox), her customers. I loved the moment of grace when Inez waves over Alicia (Tara Pacheco) and her child to get a place at the street memorial then T’s astonishment at the revelation (how did you not know?).

There is a lot about colorism. Despite his boasts to Inez, T is not into light skinned women from another ethnicity. He has a little flirtation with a girl who is like Inez in attitude and dress. Does he say these things because it is expected or to hurt his mom?

Believe it or not, when Inez first walks up to T, I had a flash of stranger danger, but pushed that instinct aside. Anyone could just walk up to these boys and take them……