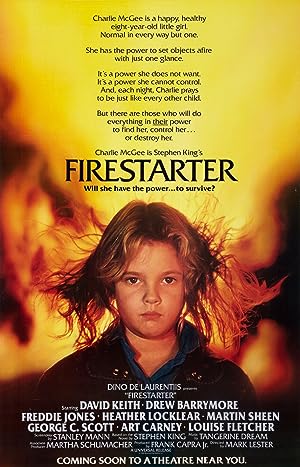

After seeing “Firestarter” (2022), I decided to rewatch the original, which I have not seen in decades since I originally saw it as a child in New York City on WPIX. “Firestarter” (1984) is a film adaptation of a Stephen King novel with Drew Barrymore as the titular character. After broke college students sign up to be subjects, two survive with powers and have a child, Charlie, but live in fear that the Shop, a shady government organization, are watching them and will take their child. Their fears become a reality, but will the government be able to hold Charlie?

Unlike the remake, “Firestarter” begins weak, but has a solid middle and ending. I hate starting in medias res and would have preferred if it was chronological instead of the father having flashbacks. The movie implies that her parents survived the experiment because instead of having a bad trip, they fell in love with each other. Charlie is an adorable kid who is concerned about the morality of her gift whereas in the remake, Charlie is more volatile. Charlie only interacts with adults, and the real protagonist is her father, Andrew McGee, and his effort to protect and guide his daughter. The family is much more normal with dad training Charlie to insure that she will not hurt anyone.

Charlie’s pyrokinesis is depicted as less a part of her, but almost as if it is like a possession, a force that she channels and cannot control though she learns how. It is described as evil (the association of fire with hell is never explicitly stated) or godlike power. When Charlie wields her power, she is like a god delivering her judgment, so she never seems evil for using her powers except at home. Because Charlie has always been trained, the original has more scenes throughout the film of Charlie wreaking havoc instead of waiting until the denouement to really let loose. If the Charlies had to fight each other, 1984 Charlie would kick 2022 Charlie’s butt, but if they had the same amount of training, 2022 Charlie would win because she is meaner, has a warped sense of morality and has more powers. Original Charlie is not a serial killer and protects animals.

Because the original film is more fleshed out, especially in terms of the Shop, which is just the nickname for the Department of Scientific Intelligence, it is more noticeable how few women are in the movie. The mom gets fridged in both films, which is faithful to the novel, but women adhere to gender norms in this film, and mom just acts as an echo chamber for dad. They are at home and doing housework with few lines. Heather Locklear makes her first film appearance as Mama McGee. Louise Fletcher plays Irv’s wife, but she adds an edge to her secret glances to her husband and while delivering lines to imply that her husband is a dumbass who just got them involved in some mess. It is more than Irv’s wife got in the remake, but to be fair, Fletcher probably would have stolen every scene without any lines and bedridden.

Irv (Art Carney), the friendly random man who picks them while hitchhiking, serves as an everyman American who is outraged at the government’s illegal actions. He acts as the moral barometer for the film. Because he is against the Shop, it acquits the McGees of any wrongdoing when they use their powers. When Charlie has her “Carrie” moment, she never seems like a monster or a vigilante, but meting out justice. These scenes are not flawless because the dialogue repeats a lot of what “Firestarter” showed in earlier scenes. The film has a faith that if people knew the truth, the McGees would be safe.

The central focus of this “Firestarter” is which man will Charlie choose: her dad or Rainbird (George C Scott), a Shop employee disguised as an orderly who is really an assassin? I did not notice this theme when I watched it as a kid, but as an adult, while dad and daughter scenes are normal, they also feel a little off, especially in retrospect after she starts hanging out with Rainbird. She does a lot of the caretaking of her dad, and if her lines were given to a girlfriend in a different context, it would not be out of place, especially in the scene where she is just wearing a shirt and sitting in front of a fire in a cabin with her dad. It makes her accidental attack on mom feel more intentional as if she was jealous of mom trying to get her to stop spending time with her dad whereas mom was only concerned with her well-being. Rainbird and dad battle over her power and soul, but also her affections. The film uses sci-fi and horror to meditate on parental concerns, including child abuse.

Because the original adheres closer to its source material, Scott has more to work with when developing Rainbird, a sick and twisted person who not only wants to kill Charlie to gain her powers, but enjoys spending time with her, manipulating her, and winning her trust. When he tranquilizes the McGees, Scott has this great moment where he yanks the unconscious Charlie from her dad’s arm with disdain for him. It is an early example of a frequent King theme of evildoers tricking powered children into trusting them. The central act compares how the Shop treat Charlie and the dad, and the essential ingredient for the Shop to exploit Charlie is to keep them separated so even though the head of the Shop, Captain Hollister (Martin Sheen) is disgusted by Rainbird’s predilections, their interests are aligned. “Firestarter” is at its best when Scott seizes central focus, and if people remember the movie fondly, his performance as the two-faced killer. We seamlessly see him as he truly is and as he wants Charlie to see him. Scott is playing on multiple levels as a master thespian as master manipulator. When he coolly comes out of the woods with multiple fearful men in fire retardant suits backing him up, it tells us more about this man, and why he was the only one who could catch them without powers. He teases his Shop colleagues for being afraid of a little girl and is unfazed by their threats.

Is Scott’s Rainbird Native American? If he is, it is a problematic depiction, especially since Native Americans did not contribute in any way to develop his character, and he is a villain. Even though scientists created Charlie’s powers, Rainbird’s demented mysticism seems to have more of a handle on their powers than others in the Shop, which continues the stereotype that Native Americans are innately more connected. He wears his hair long. He wears clothes distinct from others in the Shop-leather and one hour one minute in, he wears a coat that appears to be inspired by Native American patterns. The film exploits the implicit colonial propaganda that Native Americans will kidnap and hurt kids and women. Also casting Scott is part of an unfortunate, even if unintentional, pattern of “playing Indian,” which obliterates Native American reality and continues a tradition of minstrelsy. Negative images in the media also harms Native American children.

The original’s special effects still hold up, but the obsession with hair and powers is weird in retrospect. Charlie’s hair blows when she uses her powers, which is less strange than when David Keith as her dad holds his hair when he uses his power. Their powers are mental, but it is a little silly.

While a little old-fashioned, the original is still a solid film with an overall better cast. It is more consistent than the remake in terms of cast and character development, but it does ignore the fact that a girl with powers just killed a ton of people and is supposed to just go back to normal life as if nothing happened whereas the remake is less afraid of Charlie being scary.