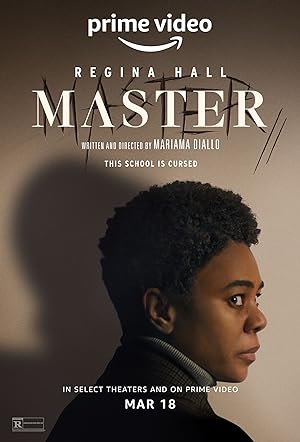

Black women wrote, directed and played leading roles in “Master” (2022), a horror film set in Ancaster, a fictional prestigious New England college as old as the country itself. It toggles between following Jasmine (Zoe Renee), a freshman assigned living quarters with a tragic past, and Gail Bishop (Regina Hall), a tenured professor and the first black woman to get the title of Master as head of one of the residential dorms, Belleville House. Each woman has unsettling encounters upon arriving in their respective new homes, which dampens their initial enthusiasm over their professional success. What will they sacrifice to get a seat at the table?

Usually when I watch a horror film, I ask myself what explains the horror: science, supernatural or a crazy person? If you approach “Master” in a similar way, you are going to feel ripped off. Instead of jump scares, the filmmaker uses racism as portends. A viewer may mistake this film’s use of racism as a rip off or homage to “Get Out” (2017). It is not. Mariama Diallo’s feature directorial debut is part of an emerging horror genre like a superb, little-known film called “Relic” (2020) or the annoying, but renown “It Comes at Night” (2017). I do not believe that this genre has a name yet so I will call it expressionist horror. These films depict real life fears such as racism or aging as if they are supernatural or how the characters’ psychologically experience them so the viewers can become submerged in the horror of that phenomenon. As Gail explains to Jasmine, “It’s not ghosts. It’s not supernatural. It’s America, and it’s everywhere.” There is no safe place, no home. Diallo’s thesis is that racism is a sufficient root for horror, and nothing else is needed; however by tossing in a vague legend about a witch, it may have been more of a detraction than a clever narrative misdirection for viewers who were left grasping for a more sensational explanation behind the women’s woes.

For Diallo, the horror of “Master” is the siren song of universities attracting students of color without warning them of the real dangers behind their hallowed halls. The cover up of racism is paralleled with how schools hide sexual assault statistics from unsuspecting freshman as detailed in “The Hunting Ground” (2015), a documentary about how colleges care more about their reputations than their students’ safety. While the story is focused on Jasmine and Gail, Jasmine’s roommate, Amelia, is another potential casualty of the campus as white sepulcher, inviting on the surface yet hiding death and doom from the unsuspecting. Gail is the intersection of power and powerlessness. Diallo asks if Gail will become complicit and/or a victim by allowing Ancaster to borrow her credibility to hide its culpability?

IMDb’s description of “Master” focuses on two black women, but it was intriguing that Amazon’s description focuses on three women. The third woman is Liv (Amber Gray), Gail’s friend and Jasmine’s professor. Viewers can be forgiven for associating her with Rachel Dolezal and thinking that Liv is the villain. Liv is too much—so woke that her results end up being regressive—hurting the black women that she thinks that she aligns herself with and stereotyping them as much as others. She favors white students who admit to filling their papers with bullshit because she does not see her own so bullshit sounds genuine. Diallo treats Liv with more ambiguity and understanding than initial impressions may imply. She refuses to give us definitive answers about Liv’s motives other than needing to belong or the identity of the hate crime’s culprit though she benefits the most. Diallo shows that Liv considers this campus as her home and delivers an eleventh hour reveal about her origins which could explain some of Jasmine’s visions. Liv does not share Jasmine and Gail’s disturbing experiences and lives in the surface world. While this comfort may indicate her race, a social construct with real world consequences, it also can point to something else.

If you are desperate for a supernatural explanation, a friend from my writing class provided one that sounds plausible that I will use as a springboard with some modifications. The movie does work if you define the campus grounds’ character by centuries of horrible events taking place on the land and stained with the blood of victims over centuries. Like the inhabitants of Derry in “It,” most of the residents are oblivious to the periodic need for a blood sacrifice to prosper. Only people outside the social hierarchy can discern the threat and see the red tint covering the grounds. “Master” suggests that Jasmine and Gail, as outsiders, share the ability to perceive Ancaster’s true soul, the demon of racism, like Danny pegged the Outlook as evil in “The Shining” (1980). If Haley Joel Osment saw dead people, they see racist people. Just as the dead thought they were still alive, the racist people think that they are progressive. They are the moral monsters that James Baldwin condemns in “I Am Not Your Negro” (2016). Diallo set the film outside of the South to make a point. Racism is national, not bound to a single region. Any hostile spirits would see them as intruders in a way that they would not see descendants of the original inhabitants from the seventeenth century settlers regardless of race. Any descendants or beneficiaries of this system would not be as discerning because they receive rewards from the evil, white supremacist grounds. The denouement echoes the end of “The Shining.” It also borrows elements from “The Amityville Horror” (1979), “Paranormal Activity” (2007) and the recent remake “Black Christmas” (2019). There is even a flash of Dorian Gray.

Jasmine as a sleepwalker is susceptible to slipping through spiritual dimensions and reality. After her first nightmare, her roommate is exasperated as if Jasmine has behaved strangely before. Sleepwalking also has roots in the Salem Witch Trials. If I am disappointed, it is the failure to use the movie’s witch legend to add texture to the narrative. When Jasmine traces the history of her room, she discovers a link to an earlier inhabitant, which was lost in the retelling of the legend. Diallo highlights the imagery of negatives, black and white, during this research. It was a missed opportunity for Diallo not to use the witch as another possible link, a fellow persecuted, scapegoated, and demonized woman for others to project their issues onto, a Tituba figure. Instead if I am wrong, and there is a witch spirit, she has more in common with the living racists, particularly the last one, by targeting Jasmine whereas the reality is that witches were usually misjudged women.

I did appreciate that while Jasmine’s friendships were not nourishing, her ties to Cressida (“Anna and the Apocalypse” Ella Hunt) and Katie (Noa Fisher) were reciprocal. It is interesting that Diallo acknowledges it in one outdoors ceremony scene while condemning the friendship group for ridiculing Jasmine’s need to find deeper relationships with students of color with similar traumatic campus experiences. It suggests seeds of doom for them for dismissing their own fellowship needs and only seeing the surface world.

“Master” explicitly spells out its goals, but may still fail to convey them to the average viewer expecting a more conventional horror story by waiting too long to state them. It may benefit from repeat viewings. It features naturalistic and subdued performances from an excellent cast. It is a gorgeous and evocative film. While Diallo’s first feature shows promise, expressionist horror can leave audiences feeling cheated who want their horror to be more metaphorical and decipher the applicable meaning for themselves.