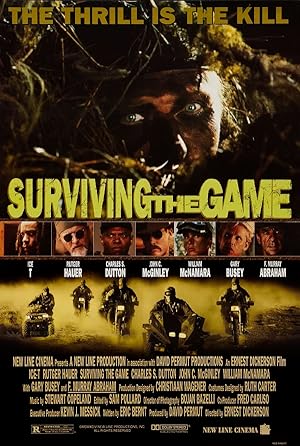

“Surviving the Game” (1994) is one of many film adaptations of Richard Connell’s short story, “The Most Dangerous Game.” Mason (Ice-T), a Seattle man who has been homeless for two years, is about to give up after experiencing more loss. Cole (Charles S. Dutton) saves his life and sends him to his business partner, Burns (Rutger Hauer), who offers him a job on a Oregon hunting trip, which Mason accepts. After a lavish dinner getting to know his employers and their customers, he discovers that they plan to hunt him. With the odds always against him, will Mason survive? Ernest Dickerson, Spike Lee’s cinematographer and prolific television series director, directed this box office flop, which was remade and called “Apex” (2021).

I do not know if paying $1.99 on Amazon influenced my perception, but “Surviving the Game” was a psychologically nuanced film thanks to the writing and acting in order of excellence: Hauer, Dutton, Gary Busey, who plays Doc Hawkins and wrote his dinner monologue, Scrubs’ John C. McGinley as oil-man Griffin, Ice-T and Oscar award winner F. Murray Abraham, who apparently has major bills and plays Wolfe, the “most feared man on Wall Street.” Hauer, who is customarily the scene stealer, chooses the counter cultural acting moves with McGinley interrupting Burns’ musings then Busey chewing the scenery and bouncing off the walls. While Dutton still has a soothing presence, his depiction of Cole has a bubbling undercurrent of eagerness to drop the mask reminiscent of Doc and is comparatively steady.

This dystopian film grounded in contemporary life, not a sci-fi futuristic world, suggests that the functional members of society are violent, homicidal maniacs who dehumanize those below them on the economic ladder because to thrive in this society, they had to embrace abusive, amoral, toxic gender normative, hierarchal social structures that killed their soul, and the have nots, whether poor or animals, are more civilized, moral, life preserving and law abiding. Each character is worthy of deep psychological analysis.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

To succeed in society, a certain amount of cruelty must be accepted. According to the rules of the game, animal and child abuse are framed as coming of age rituals to become men and replicating that homicidal dynamic is considered therapy. When the film refers to the fictional version of the CIA, it evokes an unspoken backstory of men at a later stage in life being similarly baptized into manhood when required to commit professional acts of cruelty in their home lives or other countries then wondering how to return and function in regular American society. They embrace cruelty, pain and murder as tools for success, which is not a lie. They are successful according to society’s parameters. They have families, professions, financial security, and respect. By categorizing it as therapy and keeping the details secret through distance, seclusion, and money, they maintain a veneer of respectability, but it is also rationalization of addiction to power and a death wish.

The moment that each hunter is inducted into cruelty, their soul dies, and a secret death wish emerges. At the moment of their induction, they had an alternative-to reject cruelty and classify it as wrong, but they don’t. They kill others while secretly having no regard for their own lives because they chose to kill their humanity. The hunt is compared to sex, and only hunters are real men. Considering the lack of the hunted informed consent, they probably conflate sex with rape. If men reject the hunt, they are vulnerable to being cast out of the group and hunted or considered like women. The hunted human is dehumanized and considered an animal because of his lack of success. Poverty is considered a moral failing.

Burns, an intellectual and aesthete, and Cole, an epicurean, have a fraternal dynamic. They are both calm, have their daily rituals and act in unison like twins. (Side note: I want to know how Hauer and Dutton managed to bond and get in sync before filming because it felt organic, not staged. I have seen less chemistry in biological families.) They see the hunt as an exuberant ritual that permits them to retire from the monotonous parts of their job that they disliked and keep the parts that they liked, the addiction to having power over another man’s life, i.e. killing. They tasted the forbidden fruit and liked it. Now they can make money while still doing what they love and maintaining their image as family men in civilization. They are so committed to the game that when they realize that they could lose, it is still fun to them because it is novel.

When Cole’s legs are blown off, he laughs and is delirious then gives tacit permission to Burns to kill him as an act of mercy. When Burns realizes that he could lose, he encourages Mason to kill him. He later breaks his own rules of not killing the hunted if the hunted returns to civilization. He uses Mason’s mercy as an opportunity for another kill before hitting the road and/or as an act of revenge. At a fundamental level, the killing and novelty of the game have more value than their existence or well-being even though if they do not live, they can’t play the game. Is this disregard for their own life a subconscious way of finally getting punished instead of rewarded or just the natural end to all out-of-control addictions, oblivion? Cole is the scarier of the two because like a pedophile, he convincingly places himself in positions of trust to pray on the vulnerable by working at a charity.

Even though Doc boasts that he invented the Hunt, it feels as if Burns and Cole have more control than Doc, who is unhinged and the opposite of any kind of doctor that would swear to do no harm. He has no business caring for anyone unless it is opposite day and is the first to threaten a fellow hunter. While he could be part of a trope, the bat shit psychologist, Busey does what only Busey can do by taking it up a notch complete with a “Deliverance” reference. (Side note: Matthew McConaughey is just an attractive Busey, but they have similar vocal stylings though different accents.) He is frothing at the mouth in anticipation of murder. When his life is first in danger, he reacts by trying to kill Mason, not in self-defense, but as if the hunt was not even interrupted. He models himself in stereotypical Western wear and red face paint. He is still a little boy trying to get his father’s approval. He had been dead for ages and by taking a job that is supposed to be healing, instead he helps damaged people stay under the radar and escalate. He makes playmates. For me, the real red flag for the other hunters was Burns and Cole’s lack of reaction to Doc’s death, especially since they have known each other for decades and regularly socialize outside of these hunts. They simply want to hunt.

Griffin is a man who is ill-equipped at trying to suppress his feelings, becomes hysterical with little provocation and frames the hunt as revenge by seeing Mason as a scapegoat, a substitute for the man who really caused him pain. Griffin and Mason commiserate about their loss, and Griffin no longer has the desire to kill because he can feel again by recognizing another person’s humanity. Killing another person was simply a way to exercise acceptable male emotions, a limited emotional palette of anger, so by rejecting murder and accepting that pain instead of inflicting it on someone else, he is redeemed before he is inducted. He rejects the hunt and becomes the hunted. (Side note: no man with asthma has any business going in the woods doing anything that could flare up allergies.) He has no innate desire to kill, but had a rationale. He thought that killing was an answer to a problem, but it was not.

Unlike Wolfe Jr., the group sees Griffin as a real threat who must be eliminated. He is like them, but waited too late in life to experience trauma. Instead of framing that trauma as positive, he recognizes that it is negative. He is not his true self when killing whereas they are. He is also similar in ranking and size. He is technically the first member of the team to sow division within the community by starting arguments with his fellow team members. Griffin has confrontations with Doc, Burns, Wolfe Sr and Cole, and each man considers turning their attention from Mason to Griffin. Part of the ritual is making a young, inexperienced man kill, but this older man is volatile and could kill anyone or no one. He does not abide to the rules though he pays the price of admission. The game is about reinforcing social hierarchies, but for Griffin, especially during his conversation with Mason, the game is a resource for support. He looks for therapy and finds it. While Doc, Wolfe Sr and Cole respond aggressively, Burns’ demeanor suggests that he is playing a calming influence with one hand, while he points his gun at multiple players. On some level, Burns has imagined killing every hunter and hunted based on his body language, but not his tone.

The hunt also acts as a ritual of male belonging. When Griffin rejects the hunt, he is no longer considered a part of a society and gets killed. Griffin acts as a cautionary tale to Wolfe Jr., the son of the Wall Street dude. If Wolfe Jr. does not participate, his maleness and wealth will not protect him. Wolfe Jr. is what viewers imagine these men were like, especially Doc, before trauma. He still sees Mason’s humanity. He does not want to participate in the hunt. He saves his father’s life then gets rewarded with his father and Burns manhandling him. The hunters perceive him as weak and a potential liability like Griffin. Wolfe Jr. belongs to a club that he never asked to join but is not permitted to leave without physical harm. He distinguishes himself from his father, but he still participates in hunting down Mason, and Mason sees him as more of a threat than Griffin. Since “Surviving the Game” aligns itself with Mason’s perspective, Wolfe Jr. is a threat because he knows better, but does not do better while acting as if he is morally superior for simply having the capacity to see humanity while not acting like it; however Wolfe Jr. is not a physical threat.

Wolfe Sr. is the most effeminate and not as physically intimidating as the other men. The idea that he can hang with seasoned killers is absurd, but a view of himself that he treasures. He wants to believe that his business acumen and ruthlessness translates into the real world. He cares more about the opinion of murderers than the safety of his son, whom he allows the murderers to hit because he sees hitting his son as something appropriate because he does it. On the other hand, he recognizes his son as an extension of himself and realizes in a way that never crosses Doc or Griffin’s minds that these men can and will turn on him. His money and power gave him a delusion of physical prowess that he never had as evidenced that his inexperienced son rescues him from the burning cabin. For the audience, Wolfe Sr. is what viewers imagine Doc’s father being like. Wolfe Sr. was the most annoying character because if your son needs to save your life, I do not care how many people that he has killed, he needs to take a seat. Big talker with the nerve to bully his son once he was safe. He got lucky that Jr. died because if they had succeeded in killing Mason, and Jr. started taking after Sr, there was going to be a scuffle, and Sr. would lose. Also Sr. annoyed me for expecting a morality from Mason that he did not possess himself. Hypocrite! He was the only person in the group clutching his pearls that Mason dared to try and hurt him. A real wolf allegedly appears in “Surviving the Game,” and I kept waiting for their paths to cross, but it does not. The wolf is a wild extension of all the dogs that Mason likes.

Mason is a man who cares for and respects old people and animals, specifically dogs, who like him and symbolizes that he is a good guy. When he attracts the attention of anyone in a higher social class, they react to him by inflicting physical violence from cab drivers and security guards to his employers. His assaulters perceive his existence and nonviolent criminal acts as worthy of physical, violent reprisal, especially extrajudicial execution. While Mason does defend himself, he will accept a certain amount of violence if he thinks that his assaulter’s blood lust will pass. At the beginning and end of the hunt, he stops and addresses the hunters in disbelief for their deliberate violation of convention such as the rule of hospitality when they begin the hunt and Burns’ abandonment of Mason in the wilderness at the end. He can believe that someone wants to hurt and kill him, but unlike the cab driver and security guard, these hunters do not shake off the blood lust when he confronts them as a person.

When Mason uses their tools, guns and ATVs, as intended, he stumbles and fails, but when he uses their tools in counterintuitive ways, to cut down a tree, he turns the tables. When he embraces their macho bravado to try and fit in by bragging about killing his wife and child, which is not true, but reflects his guilt, he puts himself in more danger. His real power is rooted in fire and as a mechanic. Once he and others embrace their trauma and damage instead of trying to recreate it and reframe their pain as empowering moments, they regain the moral high ground and cannot get hurt that way again. Like Bluebeard’s wife, he uncovers the hunters’ past victims and uses their preserving chemicals to burn down the cabin. When Doc tries to burn Mason’s back against the cabin, it does not work because of his previous injuries. Mason sabotages an ATV and mortally wounds Cole. Mason progresses from being suicidal and having nothing to live for to wanting to survive after rejecting being told that he is worthless and realizing that if he dies, he will have no autonomy over his body and continue to be disrespected in death. He knows that he has innate value and that his financial status is unrelated to his self-worth. He deserves not to be mutilated.

The cruelest part of “Surviving the Game” is the dinner through the next morning when the hunters rudely awake Mason. Mason finally feels as if things are turning around, and he has hope. Men from a higher class are offering him hospitality and are strange, but for the most part, friendly. Other than bringing a few beers to them and taking their luggage, he is treated like an equal. Then the next day, they pull the rug out from under him and treat him brutally by shouting him awake and beating him. It is reminiscent of how people remove underprivileged people from familiar surroundings, bestow some favor upon them then can remove it for any reason. They know that they “enjoy fucking with them.” It is part of the fun. He just wants a job and to enjoy a few creature comforts so they weaponize survival and comfort. It is not enough for the hunted to lose their lives. They want them to know what they have been missing, believe that it is attainable then take that away from them. They want to create and kill their hope.

“Surviving the Game” is problematic. It is a have your cake and eat it too movie. We condemn the hunters, and though Mason is correct to act in self-defense, by winning the game, he proves their point. It is therapy for him, and he recovers from suicidal impulses over his guilt from losing his wife and child. We embrace a demented worldview by enjoying this movie. The movie also plays for laughs the fish out of water scenario in how Mason must navigate the wilderness and is completely out of his comfort zone.

The role of religion/spirituality was underdeveloped considering what a pivotal role it plays in the denouement. There are subtle hints throughout “Surviving the Game” that Burns is/was Catholic. After revealing the rules of the game, he can barely suppress his laughter when he says that God may show mercy on Mason. During the denouement, Burns disguises himself as a Russian priest, which is only cool because he ends wielding the rosary like a weapon while reciting it. While his behavior in the costume is at odds with the beliefs it is supposed to represent—he can barely hide his revulsion at interacting with a homeless woman who asks him for money then she drops the respectful act, the film seems to be suggesting that the costume is more aligned with the wearer’s values than it should be. The veneer of civilization disguises dysfunction, and clergy are not exempt from this paradigm. The theme reflects Burns’ disillusionment with his earlier beliefs because of his professional experience where God appears to be absent yet when he believes that he is about to die, he does seem to whisper a prayer.

Considering the premise and the race of the protagonist, “Surviving the Game” never explicitly explores race even though the optics are horrible. It looks like a lynching, but I would never categorize it as one. Dickerson, who is black, chooses a more complex model of race that is underexplored, and I am uncertain whether his point lands though I appreciated it. The equation is never white equals bad, and black equals good. The security guard and Cole are black, but at least as blood thirsty as the other white hunters. Race cannot be equated with morality, and experience with oppression does not create empathy. The security guard and Cole see themselves as better than Mason because of class. There are many examples of interracial friendships. When Mason earns some money, he goes to a hotel, and there is a black guy manning the desk and distributing keys who is chatting with a white guy. Mason interrupts them as a paying customer, but when he demands not to be ripped off with getting a room with a broken television, this black guy feels zero camaraderie and chides Mason for expecting more than this hotel employee believes that Mason deserves. Dickerson recognizes that being black does not equal allegiance if the class is perceived as different. If you are black, you are still human and will embrace whatever privilege is accessible because it is nicer to feel on top than on the bottom so black people can be just as invested in enforcing a dehumanizing social hierarchy, a hate tree, which includes the branch of racism. Cole and Burns love each other, but we cannot celebrate their post racial camaraderie since it grows in a soil of exploitation and blood.

“Surviving the Game” may be a cheesy, unoriginal 90s action flick, but it has a great deal of psychological merit. And shoutout to the “Kingsman” franchise for stealing the dog killing line. Pay Busey!