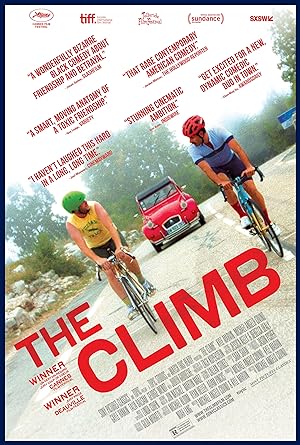

The Climb is a comedy stylistically divided into seven chapters, shot like a drama and depicts a friendship between two men, Mike and Kyle, over the course of many years as we see their relationship survive multiple betrayals. I actually laughed out loud throughout the entire film, but hesitate to wholeheartedly recommend it because of the problematic implications. Do not try this at home.

The Climb would not be out of place if it starred Will Ferrell and John C. Reilly, but unlike popular Hollywood comedies that prioritizes laughs over visual artistry, Michael Angelo Covino makes a masterful directorial debut with his lengthy/uncut long shots, random artistic sequences and a seventies aesthetic that gives the film an air of majesty that would not normally visually accompany this genre. It may remind you of Wes Anderson, but the line delivery is natural, almost improvisational, and Covino is far less precious and stylized than Anderson. Think Robert Altman’s The Player’s opening sequence except not limited to a single sequence. Such visual touches lead to an intimacy that contrasts with the actual distance of the camera then contextualizes it by setting it in a specific time and place with other characters only tertiarily forced to interact with them because of proximity yet becoming wholly absorbed into the plot regardless of original intent. Here is where the humor lies: in the absurdity of the broader context and proximity of others when contrasted with the intimacy of the characters’ dialogue and relationship. These characters have no sense of boundaries or appropriateness.

Covino wears two hats as director and one of the stars in the film as Mike, the transgressor who pushes the limits of Kyle’s kindness. The Climb never completely provides the backstory regarding why Kyle ended up being Mike’s only family, but the film uses this premise to explore the idea and beauty of unconditional love and friendship which to a certain degree shares everything. Mike is a guy who has something to prove and always needs to be on top even if it leads to him being on the bottom or the outside, but the film also casts Mike’s reprehensible qualities as a potential savior capacity to rescue submissive Kyle from his fiancé, Marissa, as too controlling.

Remember, I actually enjoyed and thought The Climb was hilarious, but I do find all the assumptions disturbing. We like and are protective over Kyle because he is a nice guy. When that niceness is placed in the context of romantic love, it is not a continuity of character traits that an adult exhibits throughout his life, but suddenly a lack of agency that his fiancé manipulates and distorts to his own advantage. When that niceness is placed in the context of family or friendship, it is a positive quality that must be unconditionally extended even when it is exploited because family and friendship are immutable relationships that demand complete acceptance. No romantic relationship can elevate to the same unconditional, acceptance as family and friendship even when the romantic partner literally becomes family. Romantic relations inevitably dissolve. My issue with that dynamic is that family and friendship in the context of this movie need to get the same demotion experienced as the romantic relationships. There is something deeply manipulative and unhealthy beneath the surface of Kyle’s family.

There is a point in The Climb when Kyle has reasonably had enough of Mike yet Kyle is admonished to basically suck it up, and once again, someone chooses Mike over Kyle that should have more allegiance with Kyle. It was at that point when I thought that Kyle’s family was worse than Mike, and Kyle and Mike’s dynamic was only possible because of Kyle’s family teaching Kyle that Kyle’s injuries must always be put aside for the same people who inflict the damage on him. It is one of those moments that you may dismiss because we are so used to the obnoxious girlfriend and assume that Kyle’s family has his back and are just trying to protect him, but I read it completely differently. Kyle is territory that everyone wants to plant a flag on and possess for their own use and anything that endangers their control over Kyle is seen as a threat and must be eliminated by any means necessary. Though Mike is not a good friend, he is also a pawn in a bigger game that started long before he came on the scene as Kyle’s friend and is similarly manipulated off to the sides when isolated from Kyle. Mike and Kyle are adults with agency while allowing themselves to be treated like children who do what they are told to do instead of thinking about who they are independent from their wants and relationships to others because they cannot imagine a world alone instead of staying in toxic relationships that do not completely serve them. Were they ever really friends or did Kyle’s family “adopt” Mike and they just got used to spending time together that they never considered another life?

In the hands of a less deft actor, Marissa could fall into stereotypes and be hateful, but Gayle Rankin infuses her character with enough sensitivity and perspicacity to understand how people see her, discard the idea of becoming more palatable to others to gain acceptance and aggressively advocates for her wants and needs in a way that may diminish her likeability points, but has an immediacy and honesty missing in Mike’s mealy-mouthed confessions and Kyle’s constant adaptation to others. When Marissa calls Mike out on his behavior and ends up in the most awkward and aggressive physical confrontation, Rankin and Covino continue The Climb’s strategy of completing a thought introduced earlier in the most unexpected, subversive way possible. For a film filled with a lot of physical humor and stunts, this one is probably the most shocking and boundary crossing. It worked for me, but in another context, would give a headache to a sexual harassment instructor. The transitions are simultaneously abrupt and seamless, which only heighten the humor.

The Climb’s moments of heightened sensitivity also involve Rankin, especially towards the end of the church sequence when she goes through a range of vulnerable emotions that she is forced to publicly display when confronted or when she quietly and briefly holds hands with Kyle at the denouement. Rankin creates a character who is forced to be strong and unflinching because no one else is living an examined life or willing to take action to make their external lives match their internal ones. She and Corvino carve out great notes of nuance in the broader comedic context and character profiles of others. She wants things and owns her wants in a fearless way.

If I had to complain about The Climb, I am disappointed that we never knew the hunk of cheese that Mike and Kyle devoured that was supposed to be eaten with the freshly baked bread. I would love a psychological, in-depth analysis of the film. If it was not a comedy, it would get a lot more recognition and respect for the distinct visual style and skill on display throughout the film.