I went to SeaWorld when I visited San Diego, California for the first time. There was a petting area for modest size stingrays then a man yanked one by the tail so he could pet it. I was outraged and complained to the nearest official, but my gut told me that nothing would get done. It was that point when I realized that any enclosures for animals for my amusement was probably evil, and animals deserved to live free and wild….where we could gradually shrink the available area that we can use in the wild then kill them. It has affected my perception of everything though not my practice. When I see dogs so excited to see each other and watch human beings hold them back or keep them apart, I reconsider how domestication has ruined animals’ psychological and social health in ways that I cannot imagine even though I adopted cats. Even when we mean well, human beings suck, but think that it is a privilege to force others to interact with us.

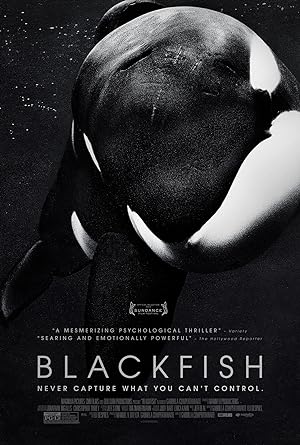

I was reluctant to see Blackfish in spite of rave reviews and encouragement from my friends because I am at the stage where I get upset if fictional animals die. I’m worried about Drogon and want to stop Bran from finding him. I stopped watching The Walking Dead because a tiger got involved. When it was about to expire on Netflix (it is currently streaming on Hulu), I finally decided to voluntarily, mentally torture myself. Because it is a documentary, mom was willing to watch it with me.

Blackfish is only eighty-one minutes long. I consider it a preach to the choir documentary because of my experience, but it also aims to persuade viewers to stop capturing killer whales and resist the image of SeaWorld as a friend of animals. It is an expose that reveals corporate corruption, ineptitude, animal cruelty then victim blaming. What sets this movie apart from other documentaries with an agenda is it embraces intellectual thrillers like Dark Waters in which there is a specific bad actor that needs to be exposed. It is not as overwhelming as radically changing the way that we live, but a tangible problem that can be fixed without dramatically affecting us as individuals. Stop assuming that amusement parks are nonprofits who care for people and animals, but look at them as forums of entertainment that are destroying lives. Our outrage can be matched with action. It easily fits the trope of the evil, unethical corporation who blames individuals for their misdeeds.

Blackfish borrows from the corporate crime movie and the environmental legal thriller, but instead of having to make boring evidence exciting to prove causation to link death and injury to corporate wrong doing, it is animal attacks, which is cinematically more appealing if you are a horror fan. It evokes the creature feature, adventure horror (think Jaws), a monster movie rooted in reality. The documentary explicitly references Orca: The Killer Whale!, a movie that I repeatedly watched on WPIX.

Like the horror movie, Blackfish humanizes the animals’ plights by explicitly referencing the cruelty that humans deliberately and inadvertently inflict on them. We kidnap their babies, confine them to a tight space, put them in social groups in which they may not speak the language then starve them. The animals are rightfully angry. The animal trainers are clueless and not experts because they get minimal training with information that is flawed. The only one with the whole story is the employer.

Blackfish uses home video footage and archival film then filmed exclusively for this documentary interviews with experts and people who were involved in some way with either the orcas or trainers. The film takes us on an emotional journey reminding us of the childlike wonder when initially confronted with nature’s massive creation. It makes the trainers relatable as they share how that experience inspired them to choose a career that would ultimately lead in disillusionment, disappointment and for some, death. Their relationship with the orcas acquits them of wrongdoing as a faceless organization drives a wedge between this bond, which the viewer may instinctually compare to their own close relationship with an animal, by not giving that person any voice in advocating for better treatment of their aquatic friends or getting deceived and manipulated into believing that they are acting appropriately. Through their innocence and naivete, we cannot accept the cover stories parroted in the news that these parks originally offered, which is to blame accidents and deaths on trainer error. The film makes it less about trainer error than a corporation failing to fully inform trainers of the risks and abusing the animals so the show can go on.

Even though Blackfish opens with the death that got the most attention, Dawn Brancheau, which occurred on February 24, 2010, it proceeds to backtrack then chronologically move forward from 1970 to prove that it was not an isolated incident. It acts as an unofficial biography of one orca’s life, Tilikum, who is now dead, as he moves through a system that never looks at him as a sentient being. Many accuse this documentary of being propaganda because it has an agenda and takes a stand, but if it is one sided, Sea World contributed by refusing to be interviewed. There is even one sea captain who is the equivalent of a John Newton figure who condemns himself for knowing that he was being evil, but not stopping; however like most good Nova episodes, I actually learned a lot about the difference between life with man and in the wild for killer whales. When this documentary was shot—it was released in 2013, one talking head claimed that there was not one incident in the wild where orcas attack people, but now in 2020, they are proactively attacking yachts near Spain.

If the victims in Blackfish are the killer whales and the trainers that love them, and the villain is the corporation, the hero is the Occupational Safety and Health, who intervenes on behalf of the trainers, with Dave Duffus as their herald. After 2016, can you imagine the federal government intervening for people over business? The court proceeding is depicted using illustrations with typed subtitles to represent the questioning and testimony, but wisely does not dominate the film because the viewers are the unofficial judges mulling over the evidence. We get more information than even OSHA knows about. The park patrons clearly testify in the film to what they witness and can identify the specific orca culprit while OSHA is unaware that it was possible. The outsider eyewitness testimony is even more damning than the official evidence since it goes back decades and directly contradicts SeaWorld’s cover story.

Who advocates for the animals? Crickets. The law still views animals as property. We do not even treat people like people so Blackfish, though an excellent documentary, is ultimately a depressing one. Tilikum lived a life in social isolation or bullying to ultimately have a psychotic break, which people knew, but he still died in captivity, alone and confined. His fate is not that different from other captive whales or other species. If humanity ever has to argue its case for continued existence, we will lose.