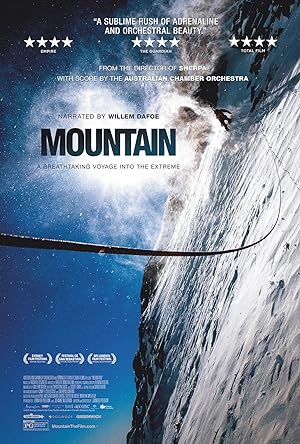

Mountain is a seventy-four minute poetic documentary with narration from Willem Dafoe speaking the narration. The narration are excerpts from Robert Macfarlane’s Mountains of the Mind: Adventures in Reaching the Summit. Richard Tognetti composed the soundtrack, which The Australian Chamber Orchestra played. Renan Ozturk shot the footage. Jennifer Peedom directed the film.

Poetic documentaries are largely abstract. It would be generous to suggest there is a narrative though there is some framework and organization to the collection of images. Mountain is the kind of documentary that you pay high ticket prices to see at the IMAX theater though it was not created to be shown in such theaters. After watching the film, I read a little about the film and got the distinct impression that there was an old fashioned impulse to create a nascent moviemaking experience with the music played live while the moviegoers watch the images on screen. Dafoe would act as the beat poet emcee live, but unseen in a nearby booth maybe where the film is being projected. This mood explains the opening images of the film which shows the orchestra setting up and Dafoe preparing to read in a nearby sound booth. Peedom wants us to be in awe of the images as early viewers were when they ducked in fear if an oncoming train suddenly appeared onscreen. This documentary is supposed to make us feel as if we are in the clouds precariously perched on the edge.

Though poetic, Mountain’s narrative should have been chronological instead of thematic, and to be suitably universal, not anthropocentric. Mountain should have evoked a predivulian world in which the mountains were just beginning to rise and fall. Instead Peedom chooses to begin with footage of humanity’s currently most famous climber, Alex Honnold. The story is dominated with man’s relationship to the mountains: madness or reverence. After sixteen minutes, there are roughly five minutes devoted to mostly black and white archival footage of early mountain climbing (women in dresses). The first and only time that we hear a person from the actual footage speak is twenty-nine minutes, but there is a montage of groans so my earlier silent film reference is not arbitrary. If you are a child of the seventies and eighties who watched ABC sports, you could call it the first of two Agony of Defeat montages. There is a somewhat depressing montage devoted to taming mountains that make them seem more like commuting freeways with heavy traffic than majestic landscapes. Skiing seems depressing. Mountains as a backdrop to extreme sports provides an impressive array of people finding new ways to navigate mountains and show off athletic prowess and daredevil skills, which naturally segues to the second montage of Agony of Defeat, crashes of doom. My mom watched the documentary with me, and I reassured that no one died in the footage, or if they did, that footage was not included.

After fifty-one minutes, Mountain revisits Everest, which dominates the entire documentary and is the only mountain explicitly referenced in the film. Peedom should have saved the best, best as defined as biggest though that seems subjective, for last in order to avoid repetition and provide a natural denouement. I did not mind the repetition since I cannot differentiate one peak from another without context clues or weather variations and am just generally impressed by any old peak. The final section devoted to volcanoes and the ebb and flow of magma and ends with time lapse footage of nature with animals as the star of the show. It gives the appearance of the Earth as a living creature that breathes albeit at a rate slower than the human eye can discern.

If you are expecting a traditional documentary in which the narration will explain to you where the footage was shot, who is on screen and what is happening, Mountain may not be for you. Mountain is not an adaptation of Macfarlane’s book in the traditional sense. I have not read the book, but it sounds as if it is a book that generally meditates on his personal and humanity’s relationship with mountains throughout history, but not in a manner that suggests Macfarlane went to a library to do exhaustive, comprehensive, international research. Rather it is a Eurocentric impressionistic perspective in spite of the images of Asian monks worshiping inside temples.

Even though I am an African American woman, I expect the default to be Eurocentric based on my upbringing, my heritage, my education, my neighborhood, my career and my biology. I am delighted to get representation, but am not from the generation that instinctually demands it, and at times, am relieved when it is omitted rather than fumbled. If I am startled when the narration made the conquering colonial experience sound as universal as the earlier and later swaths of film that discussed man’s reverential relationship to mountains then Mountain’s filmmakers had no idea that part of their audience would be disturbed, not wistfully and continuously transported, undisturbed throughout the film. “To bring it (referring to the upper world) and its people within the realm of the owned and known,” is read in the same tone as all the universal passages and archival footage of Africans carrying colonizers’ luggage accompany the language. I am not critiquing the passage per se because it is accurate. I am not criticizing Dafoe’s reading because the man is an extraordinary actor who probably took direction.

I was fully prepared for Mountain to be filled with generalizations and platitudes, but once history gets injected, the tone of the film needs to change, even briefly, and the film can no longer pretend to be a general, universal human story. Poetic structure is not a great way to tackle history. Sure Hannibal crossed the Alps, but the words were not juxtaposed with such imagery. Later the film’s narration references passages that use war terminology to describe the conquering of Everest. How can a poetic film with the pretense of an everyman universality tackle a Eurocentric, colonialist perspective when the majority of the world and its inhabitants were the ones colonized? The film should have made a choice: be universal or consciously take a particular perspective, but you cannot have both and remain poetic. The images and excerpted passages are being asked to do more than they were originally intended to do (I hope) unless Raoul Peck, the director of I Am Not Your Negro, is willing to consult. It makes later passages about men seeking out danger because life is too safe feel particularly jarring and exclusive in its scope, which is not the documentary’s intention.

Interestingly in the middle of a pandemic and an unprecedented time of socio-economic upheaval, I do not think that you need to belong to my particular demographic to roll your eyes at the idea that life is safe, and you need to seek out danger. Danger is invisible right outside your door regardless of whether or not you recognize its existence. The mountain has come to you. No disrespect intended to thespian Dafoe, but do your best to ignore the narration in Mountain, and your experience will be much more transcendent than mine.

I preferred the documentary’s perspective from the mountain’s point of view, it’s “disinterest in us.” The footage is perfect, but maybe the editing needs some work to borrow a broader perspective like Terrence Malick’s Tree of Life in its approach to the indifferent land mass. I would not recommend muting the film because you would miss the orchestral offerings.