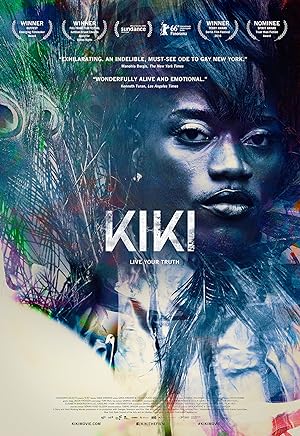

Fair or not, I watched Kiki, a documentary about LGBTQ teens and young adults of color, who vogue and participate in ball culture, with Paris Is Burning in the back of my mind. Unlike the classic, one of Kiki’s filmmakers is also the subject of the film. I kept comparing and contrasting how the community had changed decades later more than I considered the merits of the film.

Kiki is less about the ball scene, but the local community center dynamic that culminates into the ball scene, which is more humble, homespun and good natured in the spirit of theater kids without a script. While Paris Is Burning’s participants felt like fully formed adults, even the children, these interviewees were so young and felt as if they were still cooking though they were predominantly adults. Even though the film could have done more to capture their personalities, I think that it would be difficult because while they have a clear vision of themselves, they are still at that age where they do not know that they are not themselves yet and have so much more growing to do. I hope that they have long lives so we can revisit them when they are older.

Unlike Paris Is Burning, Kiki had no older people. As the ultimate proof of the devastation of a pandemic, AIDS, not Covid, there were no elder states people as there were in Paris Is Burning. The legends from the classic had experienced the culture for decades. Kiki’s Houses had mothers and fathers, but there was not a lot that distinguished the mothers and fathers from the children, and while they still provided a place of community, the houses did not convey their distinct personality or longevity in this documentary. To my middle-aged, if I’m lucky, eyes, they all seemed like contemporaries. Instead they developed their historicity not from experience, but research, and reclaimed spaces that were once proud domains of drag culture in the early twentieth century. So the loss led to a determination to reclaim a past that could have disappeared.

The subjects in Kiki are comfortable with research because while they may have gotten an education in the streets, they had more traditional opportunities for education and employment than their eighties antecedents. It is possible that those opportunities are more available because of increased home stability. More of the interviewees had family support than the interviewees in Paris Is Burning, and some family members proudly participate in the interviews, who are completely absent and only recalled as abusive in Paris Is Burning.

Because there is more language available and distinction between gender and sexual orientation, the documentary shows that the participants are consciously activists, aware of their place in the world and expecting more from it in terms of being accepted by the establishment while abandoning the respectability demanded from the establishment. Any hint of respectability politics gives way to a refreshing honesty about sex work, survival, self-medicating through drug use and wanting more from life than success in the ballroom scene. There were fewer mothers in this group, and the fathers did not adopt executive realness, but a banjee boy style that embraced more gender play than previously allowed in the eighties. Masculinity is redefined and combined with feminity.

Even though Kiki shows an objective improvement in the lives of LGBTQ teens and young adults, the interviewees recognize the insecurity of their status based on the political landscape, economic insecurity, lack of laws against discrimination and police brutality. The political landscape was at a high point-Obama welcomed one of the filmmakers to the White House and SCOTUS decided in favor of marriage equality. The issue of race consciously distinguishes these young people from confusing their plight with gay people who fit a more heteronormative image, which leads them to ask if the mainstream is worth the effort instead of strengthening the community. Advances lead to awareness of how far they have to go, and instead of bravado in the face of danger, they are unafraid to be vulnerable and say when they are triggered, afraid or suffering. They may perform, but leave the performance on the floor. They never deceive themselves into believing in anything other than reality.

Kiki still occupies the same spaces that the interviewees of Paris Is Burning did. The halls feel very reminiscent of the ones from the eighties, but the pier is still the place to vogue, chat and hang out late when there is not a ball to go to. The Village is still a refuge. Harlem is also a place to congregate, but the way that they gather feels more like a community meeting than a well-structured competition even though the stakes are higher. They compete for money, not just trophies, but the gatherings are also places of civic activism and awareness with calls to register to vote and get tested for HIV. The energy feels different as if it is a theater performance with backstage energy and preparations bleeding into the presentation space. Also the buffet style food evokes a more communal vibe than the perfect performances of the eighties. The competition may be the main event, but it is not the only one. The MCs do not steal the spotlight. The DJs use their laptops, not a turntable. The judges are dressed casually and are not a part of the spectacle. Some of the heads of houses are abruptly recruited to be judges. These are not finished projects.

While many interviewees are memorable and get a considerable amount of screentime, Kiki does not spend enough time on each interviewee, and it took awhile to get my footing. The narrative is not as cleanly structured as Paris Is Burning because the film initially creates artificial standalone performance spaces that are staged then shifts to the organic cityscapes where people vogue in public. Sara Jordeno, the filmmaker, later revisits these staged moments to contrast with the personal history of the performer to create a stark contrast of the beauty of the art with the harshness of their life. It felt forced as well as beautiful, but if a filmmaker is going to hyperstylize moments in a film, it would be better served to use that structure in service to a more complete profile of each interviewee. It is largely up to eagle-eyed viewers to catch names, aliases, which houses they belong, daily and drag persona.

While Paris Is Burning talks of travel, Kiki actually shows these young adults outside of New York and traces the roots of one of the filmmakers, Twiggy Pucci Garcon, to Virginia. He and his best friend, Chi Chi Mizrahi, prepare to travel around the world as informal ambassadors of culture, but unlike Willi Ninja, have modest ambitions instead of lofty dreams of stardom. There is a rooted in reality realness and a lack of fantasy to this generation. They may have returned to the roots that Dorian Corey missed of homemade spectacle and effort except they are more organic and tied to the imagination. There is no talk of emulating high profile figures, but transitioning to oneself. The film effectively follows Gia from her baby trans days to her now as a proud, unashamed woman. Did the filmmaker follow her longer than the others or did the filmmaker use others’ footage?

If you loved Paris Is Burning, you may find Kiki a bit wanting in comparison, but it objectively provides a fascinating glimpse into a community in the same region decades later. If you are interested in that community, it is definitely worth watching, but if you have not seen Paris Is Burning, you must watch it first.