The Institute is Stephen King’s latest novel, and I read it without knowing much about its contents. It is about a secret facility filled with people who formerly served in the military and doctors with questionable ethics that experiment on children in order to allegedly save the world, but they picked the wrong kid to play lab rat. Will this kid be able to save himself and how can one child stop a decades old black ops site?

The Institute is an uneven book, engrossing and rapid paced for stretches then droning and careless with details in others. It does not begin with the protagonist so when I started the book, I came with no presumptions and kept waiting for the other shoe to drop fully anticipating that we would circle back to that character. When I realized that it was yet another story about kids with powers that are treated like juice boxes except by scientists, not supernatural creatures like The Dark Tower series and Doctor Sleep, I have to admit that I thought, “Not again.” It felt like watching late DeNiro performances without Bradley Cooper, a caricature of his past self.

For a hard-cover book that is five hundred sixty-one pages, The Institute felt hastily written or at least awkwardly edited. King is a living, breathing ATM, and I am not going to pretend that I would not read his grocery lists if it was compiled in a book, but this book needed a lot more work before it went to publication. It felt as if because King and his editor knew the overall story so well that when they started to edit it, they did not notice that King forgot to convey certain information to his characters within the story. For example, the protagonist is aware that a character was two-faced, but there is no connecting tissue regarding how he knew it. It could have easily been explained because of the kid’s powers, but it is not. They simply forgot.

King seems eager to layout as many elements and characters as possible, but does little to distinguish each from the other. The Institute feels like the last few chapters in the final book in The Hunger Games trilogy. A lot of characters get introduced simply to act as grist in the mill. As characters were still being introduced in the final act, it felt less like Lord of the Rings and more like Peter Jackson’s Hobbit trilogy—please just end it. There is no character development. A lot happens to the characters, but they do not change or explore different notes to their characters. The good guys are good. The bad guys are bad. King can’t wait to turn the tables and change the power dynamics. The way that he does it is unpredictable even with the Bible quotes that start the novel, but once I got to the denouement, it did feel as if he had imagined certain scenes and wanted them to play out a certain way, was really attached to the protagonist and the first character meeting, but maybe he should have explored the possibility of reserving these delightful imagined scenes for another book and restricting all action to the titular location. It would have provided more thorny, moral texture as he did in his script, The Storm of the Century.

King just seemed really attached to the idea of the first character that he introduces in The Institute to the detriment of all the others. It dilutes focus from the protagonist, makes the characters in immediate proximity to him exist solely to flesh him out, including a mixture of the most extraneous, rapid and mildly insulting love story in which this person is elevated just because of King’s investment and attachment to the character, and ends up being redundant if King was not so eager to kill off another character who could have easily acted as the kids’ adult savior. I have no idea why King did this, but he must relate deeply to that character. It gives that character a chance to touch on hot button news topics that are completely irrelevant to the overall story, simultaneously create a world where none of the characters see race yet they are deep in the South with guns constantly at the ready. It is a dissonant, unnecessary mix in which he gets to embrace his attraction to the red state while pretending it has the sensibilities of a blue state when even the bluest state has shocking splotches of purples. He should have left the politics more implicit because it fails to resonate with the whole story.

If King had restricted his focus to the characters in The Institute, it would have permitted more time to establish a rhythm and learn more about the kids as individuals, which would have made their journey to the Back Half more harrowing because we could more fully compare and contrast them before and after the most intense experiments. In the end, King has more in common with the employees at The Institute than the kids. He uses them to get the sensational results, but does not give more than a few of them enough time to breathe and treated as three dimensional human beings. Most of his characters, including the heroes, are hastily drawn archetypes given the same dignity as dominoes in a Rube Goldbergian narrative that could have been streamlined and distilled into something more potent because overall it is a great idea for a story.

The Institute also sports King’s emerging weakness that is becoming a trademark in his novels. The dialogue is dated and awkward. It is apparent that he is writing as he would when he was the age of the characters, not how characters that age would talk and act now. The only problem with becoming older is spotting these anachronistic depictions of people in their forties now that I am their age. When I was a kid, I took his characters at face value, but now I know too much. It has been awhile since he actually had young kids, and it is showing. There is no shame in setting all his future books in a period that he initimately knows. I would simply have to believe him instead of finding myself pulled out of the book because it did not feel real.

The Institute is overall a solid story, but King’s instincts on how to tell that story are not as deft as they used to be. In the end, it feels like fiction when it is not that far from real life considering that our government openly puts kids in cages and separates them from their parents. I sympathize with his editors because it is not as if King is not getting financially rewarded for being a shadow of his greatness, but he can do better, and it was already on the page, he just needed more time with the story and a willingness to reserve the characters and scenarios that may work better in another book. While his latest novel is entertaining, it feels as if he is copying and pasting from the past to get present success.

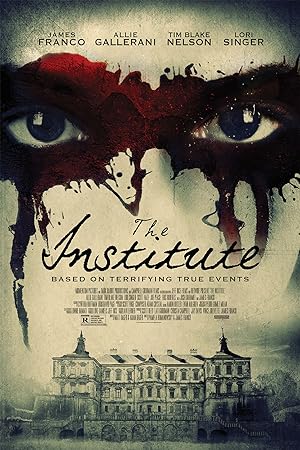

The Institute

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.