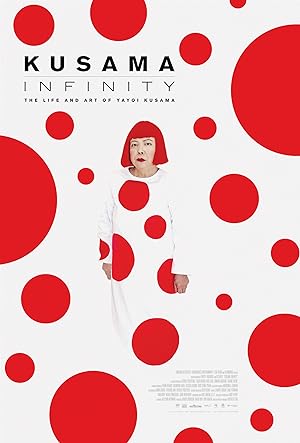

Kusama: Infinity- The Life and Art of Yayoi Kusama is a seventy-six minute documentary about the titular artist’s ninety year life. I decided not to see it in the theaters because I was unfamiliar with the artist, and it was not in theaters very long, but I did add it to my queue because I’m always interested in learning about women who have accomplished notable achievements. I also thought that my mom would enjoy it, which means home viewing. I made the right choice.

Kusama: Infinity is a solid introduction, but for such a pioneering woman, the documentary seemed too tame, conventional and safe to fully convey her life story. It is an expository documentary, which I normally enjoy—think PBS. While it definitely takes Kusama’s side, its outrage on her behalf, and she deserves to have a ton of outrage, is temperate, measured and soft-spoken, not angry. I’d love to know what a documentary about Kusama would look like if the filmmaker were furious and not at all concerned about appearing reasonable.

Kusama: Infinity has an incredible catalogue of all the things that Kusama would be mad about: parentification, child labor conscription during WWII Japan, racism and xenophobia in America, misogyny everywhere, her contemporary artists successfully plagiarizing her work while people simultaneously denigrating and minimizing her work. Even if she was not angry, the depiction of her anti-war sentiment during the Vietnam War does not convey the passion and sheer stubbornness against overwhelming disapproval it takes to make an unpopular stance, especially if you are a foreign, Asian woman in America. The documentary lightly addresses each of these separate issues, but the treatment never feels urgently intersectional. Generally the default is to file Kusama’s troubles under woman in a male dominated (artistic) world, which is too reductive.

I think part of the problem is our current socioeconomic conditions, which makes us blind to these issues because she is part of the “model minority.” Andrew Hacker, an American political scientist, in Two Nations: Black and White, Separate, Hostile, Unequal, addresses how different groups who were historically not considered white can graduate to whiteness. For example, Italians and Irish people experienced this phenomenon. I’m not saying that this phenomenon has happened for Asian people, but the process has certainly started. Historically because of Japan’s dominant financial and political position on the world stage, especially during the eighties, even though Asian people can still be seen as other, people will not necessarily see them like minorities because the stereotypes are positive. Even today, these positive stereotypes do not mean there isn’t negative treatment, but I can’t speak to that experience except anecdotally; however it is obvious that at least initially Kusama did not live in our current cultural climate. Kusama’s boyfriend’s mother didn’t dump water on her head because she is a woman. Being Japanese in America after World War II must have been incredibly difficult in unimaginable ways. This documentary could have helped us understand her experience.

I also thought that Kusama: Infinity was too coy about her mental illness. Kusama actually indicates that she had a mental disability since she was a child, but we never find out the formal diagnosis. I think that the documentary missed two opportunities. It passed on the chance to explore Kusama’s disability although the film does allude to how it influenced her work and how she saw the world in images of infinity. It also dropped the ball by failing to examine how society’s disparate views of gendered mental illness affected Kusama’s life.

Many artists live with mental illness, but it is unusual for an artist of her renown to basically be actively institutionalized while still working. She basically has handlers. Here was a perfect opportunity to really delve into how being a woman results in different treatment although in her case, this disparate treatment ends up being beneficial because unlike her contemporaries who mostly died early, some self-destructively, she is still trucking. I’m not a mental health expert or a medical professional, but as an active observer of how medical professionals treat people with mental illness, I would say that we’re still very primitive. People are more likely to be shocked and willing to intervene in the face of mad women regardless of whether or not they actually have a mental illness whereas a mad man is more likely to be seen as normal although his actions are more likely to cause harm even if he is known to have a mental illness. People are more comfortable exercising control over women than men. Inherent in the socialized worldview of masculinity is an expectation of a certain level of abhorrent conduct, which includes some violent acts, including some socially acceptable forms of murder to protect masculinity. The bar is much lower for women. Simply violating social norms is considered an act worthy of punishment for women and a harbinger of craziness, and Kusama would definitely be found guilty.

I also think if one drills down into the issue of how society treats women whom they consider mentally ill, that often age plays a role. Young and crazy often equals sexy and acceptable, which can also lead to success, but I don’t think that it is a coincidence that when Kusama was middle aged, what success she had diminished, she had to return home seen as a failure and her mental illness begins to get formally treated. All these issues are related, and her individual story speaks to a broader, fascinating phenomenon about aging women with careers may suffer more identity crisis than men because they are not as rewarded for the same work which can exacerbate underlying mental disability, which may have left the person functional when the illness coexisted with a vibrant and engaging career, but can take center stage when that career is anticlimactic.

Kusama: Infinity had access to the artist, but I was disappointed that we didn’t hear more from her regarding her past. It is dominated by talking heads. It is possible that the filmmakers time with her limited, there was not enough funding to prepare subtitles for longer than it already had or maybe the artist herself was not capable of or did not want to share more than she did. For example, I would have loved to hear more about her clothing choices. She was a very modern woman who consciously decided to start donning a kimono then reverted back to contemporary dress. Those choices mean something, and I don’t have to theorize what they are.

Kusama: Infinity failed to see the forest from the trees. It did a good job as a cinematic Cliff notes to Kusama’s life, but it fell short from making its mark as the definitive documentary. There is so much more that could be done. I would definitely recommend it, but keep your expectations low so you won’t be disappointed.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.