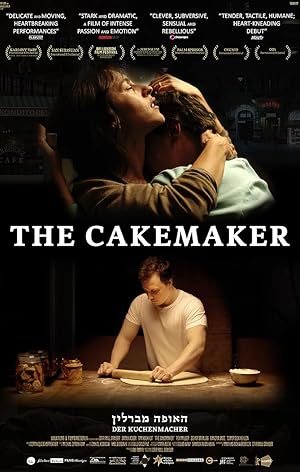

The Cakemaker is about the titular character, a German baker, who provides a literal and figurative feast that benefits the one that he loves while subsisting on the crumbs that tumble off of life’s table soon to be denied those as well. When his married Israeli lover dies, he leaves Berlin and goes to Jerusalem to be as close to the memory of his lover as possible, which leads to an increasingly close relationship with his lover’s widow and extended family, who are unaware of his true identity.

When The Cakemaker came to theaters, there were four other movies that I wanted to see more that premiered that weekend: Whitney, Three Identical Strangers, which I still have yet to see, but will, Ant-Man and The Wasp, and Boundaries, which only lasted in theaters for a week so I placed it in the queue. The reason that this movie made the cut was because it was a top priority for a friend, and life is about compromise. I got Whitney. She got The Cakemaker.

While I enjoyed the preview for The Cakemaker, I kind of despise the setup. It feels like an international, mournful Kissing Jessica Stein in which a homosexual relationship acts as a segway to a heterosexual relationship or a more acceptable way of getting to a ménage a trois without actually depicting one. It feels like polygamy for those who are afraid to really go there like Professor Marston and the Wonder Woman, which is not as satisfying or comprehensive movie. It also trucks in a trope that I’ve noticed in movies in which a widow gets to have her cake and eat it too. She gets to be the devoted, loving and faithful wife while the audience also gets a romance with a new guy without the guilt. I find it viscerally off-putting and prurient instead of genuine and textured about the complicated nature of love. Someone always gets the short shrift and is not a three-dimensional character in this scenario.

I understand that movies require a certain amount of suspension of disbelief, but very few people can financially and logistically afford to leave their life behind, move to another city in a different country for an indefinite amount of time and still expect to return home with the same life waiting for you. Even if you are the loneliest person on Earth with no friends and family, there is work to consider, and the main character is defined by his work so this aspect of the story feels like a cinematic contrivance, not plausible, and stopped me from fully becoming absorbed in the story, which is otherwise quite realistic. It is how he expresses himself, a self-portrait that he generously offers and expresses frustration when his pastries are rejected.

The Cakemaker is a strong movie because it becomes more of a portrait of societal barriers, specifically the unspoken historical barriers of a German Gentile seeking refuge in Jerusalem, and the religious boundaries that enforce this separation. Even before it explicitly becomes a part of the plot, the importance of being Kosher is almost its own character. It not only separates him from potentially everyone else in Jerusalem, but it separates the locals from each other. Lately I’ve been watching Israeli films, which are increasingly hitting the radar of mainstream American audiences. Practical daily life as it intersects with the conflict of the best way to express devotion is the primary concern of the characters in these movies. For the widow, she is not religious, but without her husband, she is losing the battleground for her son’s soul and her livelihood, the café, as she has to depend on her religiously conservative brother-in-law to help both survive. She makes a choice to give up her principles of acceptance and her (lack of) religious beliefs to function, but the baker’s presence begins to empower her to quietly reassert her identity.

So instead of a magical Negro, the main character becomes the magical bisexual who enriches her life while basically getting nothing in return. In The Cakemaker, Tim Kalkhof plays the titular character and acts incredibly well considering how little he is given. His ugly cry, complete with snot and blubbering, deserves an Oscar. If any other person played this role, there is a danger of falling prey to the Scylla of seeming like a psycho stalker and the Charybdis of not feeling like a real person. The entire cast brings more to the screen than is on the page.

The Cakemaker depicts this idea of how different people can occupy the same literal and psychological space in spite of all these barriers. Because I had the misfortune of occupying a front row seat, I had to consciously force myself to shift my focus and look at different parts of the screen, and in the beginning of the movie, the widow and the baker almost exclusively occupy opposite sides of the screen even if they are not in the same scene, but as they begin to interact more, they begin to occupy the center. Also even though two different major international metropolises provide the backdrop of the film, there is not much that visually distinguishes them from the each other. They occupy similar physical spaces whereas before they occupied the same sexual space in relation to the husband either consciously for the baker or unconsciously for the wife. They have more in common than expected. The mother in law character was the most satisfying character for me. It is only the human, aural command reminding them of God that both creates community and destroys it.

There are a couple of scenes that should be moments of recreation and relaxation that seem vigilant and guarded as if the space in Israel is actually like a prison, and the main character is eyed with suspicion while at a pool by a lifeguard pacing the perimeter and at a park by a man rising from the bench and walking away. The Cakemaker worked for me when it focused on how confining daily life was, and how depending on the point in time and location, the suspicious other is a white European.

While the denouement practically writes itself and is expected, the way that it plays out is as if society is reclaiming its space against openness and a possibility of commonality. I don’t question or disagree with the widow’s reaction, but the method that she chooses to use. It makes a human and understandable move into a craven, convenient act that erases all the psychological progress that she made gradually throughout The Cakemaker. I was disappointed in her. She is willing to claim the conservative religious protections while utilizing the language and benefits of inclusiveness and liberality.

While I enjoyed the movie more than I expected to, if subtitles are a turn off, I’d keep moving if you hate subtitles and save the reading for a book. I was vaguely unsatisfied with the overall story, but the unspoken chronicle of secular and religious life of the local and the stranger in Jerusalem was the real masterpiece of The Cakemaker.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.