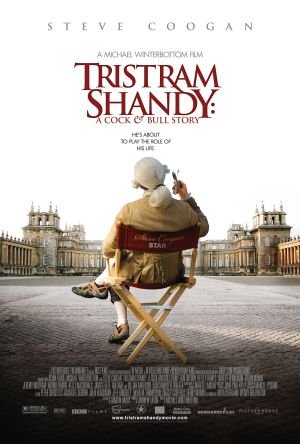

The only reason that I watched Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story is because it is unofficially the first film in which Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon play fictional versions of themselves in a fictional movie before The Trip franchise started. I am a completist sequentialist so it was slightly discomfiting to discover after watching the franchise that The Trip wasn’t the first. Otherwise this film would have never landed in my home, but unbelievably it is in high demand because I could not renew it the maximum number of times so what do I know.

The premise of Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story is that it is a movie within a movie, which in the first half shows clips from the film adaptation of a novel with the same name and in the second half reveals the behind the scenes drama surrounding the production to its public reception. Coogan and Brydon are costars, but the focus of the film is primarily Coogan as he struggles to balance fatherhood, his girlfriend and the demands of the set and his libido. He wants to remain the star on the set, use the movie as an autobiographical way to explore his evolving identity and hides his general ignorance of the novel which results in suggestions that detract from his primarily goal. It is not until the final scene of the film that the familiar Coogan and Brydon dynamic appears, which probably inspire the subsequently released Trip franchise.

The theme of the first half of Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story is the humor inherent in how women must respectfully navigate the ignorant, arrogant confidence of the men in charge of their lives and how life stubbornly refuses to bend to human will. The second half compares and contrasts artistic integrity or realness being subservient to the desired image. Whenever Coogan tries to bond with his girlfriend, in one devastatingly absurd scene, one of the people on set gives him the acting baby to bond with, which he immediately does. What ties both halves together is the vanity of men which results in so much action that adds up to nothing at all, not even a particularly funny whole although it is funny in a “that’s funny” way when you’re not actually LOL.

I’m sure that it was the point, and I missed it, but it was really distracting for the focus to be on Coogan when there were so many more interesting, better known actors in smaller roles: Benedict Wong, Jeremy Northam, Kelly Macdonald and Naomie Harris. When Gillian Anderson appears as herself, this point become clear, but unlike The Trip franchise, I could never suspend disbelief and pretend that I was partially watching a documentary because I may not know what Michael Winterbottom, the director of Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story and the Trip franchise, looks like, but I know that he is not Northam, whom I haven’t seen in ages, but he still looks good.

I’m not sure what the goal is for these fake documentaries in which the headliners are playing a fictional version of themselves. Is it like Ocean’s Eleven in which you make a movie with all your friends so you can have fun, but pretend it is work and kill two birds with one stone? Is there a deeper philosophical impulse that is being elaborated on about the movie making and consuming business in which it strips the fictional veneer for an equally fictional version of reality? If I liked the movies more, I could probably think about it more rigorously and arrive at a sensible conclusion, which I may have already discerned, but I don’t think that I actually care.

It doesn’t matter how clever or expertly executed Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story, Winterbottom’s movies just wash over me and fail to make a long lasting impression on me even when I enjoy them. Ultimately shortly after finishing these movies, they evaporate into nothing and leave me feeling vaguely dissatisfied. Winterbottom’s fictionalization of the reality of semi-famous people is not my cup of tea.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.