This review was originally published on Roarfeminist.org

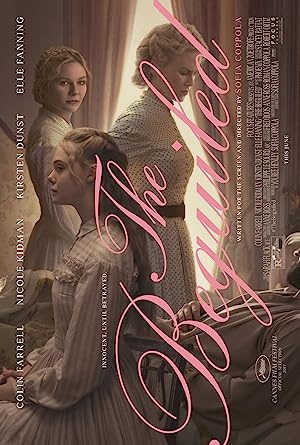

When people say, “If a woman was in charge, things would be better,” I’m always the jerk in the room who says, “No,” because 53% of white women voted for Presidon’t and suppose the woman in charge was Michelle Bachmann. Usually my reviews are optimistic so unlike most reviewers who list their favorites for the year, I will be starting a mournful new annual tradition of the Potemkin Village Feminist Award, which I hope will encourage women in the filmmaking industry to do better in the coming new year. I hope that I will not be able to give it annually. For the most aggravating cinematic moment of 2017, I give the award to Sofia Ford Coppola for the remake of The Beguiled.

I have no idea who SFC voted for, and I would choose her over Bachmann every day of the year for any political activity without knowing her stance on any issue because at least I like some of her movies. Her version of The Beguiled was heralded as the woman’s perspective even though she omitted a black woman character because she did not think that she could successfully address issues of race. Then, bitch, don’t make a movie about the Civil War set in the South (imagine clapping after every word). If your feminism isn’t intersectional, then it is not feminism. I had a chance to see the movie for free in the theaters and chose a walk through the city on a sunny day while talking to a friend. SFC doesn’t deserve money from someone else’s pocket.

I decided that I would watch her version and the original directed by Don Siegel, the director of Dirty Harry, and released in 1971, once her version became available on DVD. I also decided to give her an unfair advantage by watching her movie first because I generally enjoy the first film more than the second or the older version more than the newer. It did not make a difference. Even if you cut every scene with Hattie, the black woman, from Don Siegel’s version, his version is a better movie. Just because you are a woman does not mean that you are better equipped to tell a story than a man. SFC has some nerve implying that the original does not provide the woman’s perspective, only the man’s. Did SFC watch the original?

The Beguiled is about a single sex girl school rescuing and harboring a wounded Yankee soldier instead of turning him over to the Confederates to be imprisoned and face a slow death. They claim that once he is better, they will turn him over or send him away to rejoin his troops, but no one really wants him to go, especially him. They give an inch, and he takes a mile with dramatic consequences, which irrevocably alters the dynamic and forces characters to take action to rectify the situation. Even though neither movie deviates from the framework of the story, SFC cuts out more than just one character. She privileges atmosphere, manner and production values over psychological complexity and the full range of human emotion to oversimplify the situation into women against men. She erases everything that makes them interesting, particularly any flaws in her women characters, and makes the Southern men shadows against a wall instead of an additional threat that the women must navigate to survive. She makes one man emblematic of all male venality while simultaneously making it weaker and less intentional and all the women into victims who must subvert his plans by using traditional female activities as weapons. In Siegel’s version, everything is far more complex, premeditated and sinister, and the sense of foreboding is thick from the beginning. He takes a moment to establish what the characters are like before the Yankee arrives so when the characters change, the audience will notice the difference. Each character plays musical chairs regarding who is the prey and who is the predator. One version is superficial, and the other is substantive.

Feminism is not about matriarchy over patriarchy, but the right for women and men to be people with flaws and assets and equal opportunities to make any choice they want. Siegel’s version depicts flawed characters rooted in a specific time and place with conflicting desires and standards, which we see because we are privy to their thoughts and dreams. Siegel leaves us with a chilling image that the Southern men may have lost, but the deviancy of Southern life and revisionist history survived and would be passed down through its women. SFC’s version is a fantasy that erases the physical and psychological toll of war, romanticizes the genteel plantation and feminine spaces while erasing the black bodies and the white female depravity that made slavery possible, excises the characters’ history and inexplicably speeds up certain events to create a false narrative of female empowerment over male exploitation. SFC is the person that wants to have a plantation wedding because she wants to play pretty princess and does not get why some of her friends distanced themselves from her or gently tried to persuade her to choose a different venue. Do not romanticize America’s Auschwitz or the people who ran it.

I think that Siegel’s version embarrasses women because his women are slave holders, predators, exploiters, lazy, lack solidarity with each other and scapegoat their victim, Hattie, the only character, male or female, whose exterior matches her interior life. Sorry, but not all women are innately good. The war provides them a freedom, not to make a better system from the men who dominated them, but to simply trade places, and the prospect of losing that power frightens them. They know how to navigate the predations of the Southern men (when they want to), but the Northern men are unknown territory. Are they also a threat or a better alternative? They are motivated by self-interest and only act collectively when he destroys the illusion that he will give them what they want: sex, money, company, flattery, labor. They sweat. They have forbidden sexual desires. They are not uniformly beautiful. They are not the image of Southern womanhood on a pedestal that their propaganda touted or that SFC continues to promulgate and fetishizes.

For a perfect example of this phenomenon, compare and contrast the character of Edwina. In SFC’s version, she instantaneously falls for the Yank, inexplicably wants to leave the school despite showing no earlier signs of dissatisfaction then decides to shoot her shot. It is almost as if he is the last man on Earth, and none of it makes any sense other than hormones. In Siegel’s version, we first meet Edwina, played by Elizabeth Hartman, when she gets a promotion. Hartman’s face projects equal parts joy and horror at the realization that she will become like her boss, played by Geraldine Page, who looks at her with a tinge of lust, which is confirmed in a later provocative, blasphemous dream sequence. This scene alone explains why Edwina is vulnerable to the Yank despite knowing better: anything is better than her prospective future. Her role in his demise is less accidental and understandable and more filled with rage and denial. Kristen Dunst can do that, but she was not given the opportunity. Edwina keeps trying to find the escape hatch from what she knows: a world that accepts lies about sex and love.

Also when are we going to stop acting surprised that women can be deadly and resourceful? If you have been watching Nicole Kidman’s career for more than a minute in such films as Dead Calm, it is not so much a case of turning the tables as realizing the table was always set in that place before you got there. In SFC’s version, the women are acting in collaborative self-defense. The head mistress never lost her patriotism and is a noble woman protecting her children from becoming hostages, but in Siegel’s version, only two students retain their patriotism, but the other women’s motivations are more ambiguous, a mixture of vengeance and self-defense. They would gladly commit treason against the Confederacy and discard theories such as patriotism for real world benefits. The head mistress is also more manipulative and perverts the girls’ reaction into something more sinister, protecting her image in the eyes of community, hiding her deviant behavior and teaching them to be Southern women: how to revise history and maintain the delicate façade while being more sinister and deadly. It is a far more terrifying and iconic ending—Dirty Harry, zero, the flower of Southern womanhood, one. Is Misery’s Annie Wilkes related?

SFC wants to romanticize America’s Auschwitz into an image of female solidarity against male tyranny by erasing everything that made them real. It is a Stepford wife fantasy that would make her quite welcome at Siegel’s Ms. Farnsworth’s table. Distract them with our fabric and meals so they won’t notice how poisonous we actually are. The Antebellum South would thank her for her service.