This review was originally published on Roarfeminist.org

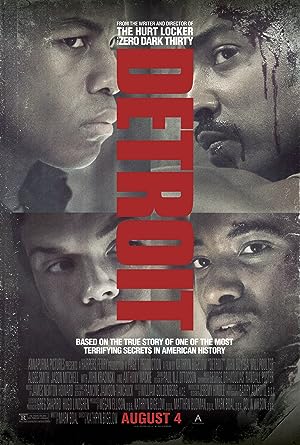

I loved Kathryn Bigelow’s films long before she received an Oscar: Near Dark, Blue Steel, Point Break, Strange Days, K-19: The Widowmaker. I was not into The Hurt Locker, but she regained my favor with Zero Dark Thirty. Bigelow’s films generally focus on one main character, usually a man or a woman in a traditionally male role. The main character is a person who does not belong in the mainstream or the outlaw world, but navigates both with tremendous difficulty and an allegiance to achieving a specific, noble goal. I would not be surprised if Bigelow does not relate to her main characters. She is a woman director who excels at action drama movies, a genre in which women rarely appear behind the camera. Bigelow’s films usually present a moral dilemma while asking her viewer if all the effort expended throughout the film was worth it.

Bigelow appeared on The Daily Show to promote Detroit and admitted that she was the wrong person to tell the story, but the story was too important not to tell. I appreciated her honesty and saw her willingness to tackle injustice at this particular time in our nation’s history as her cry of resistance. Post Trayvon Martin, you can tell a lot about a person by the stances that the person takes in issues involving extrajudicial executions ratified by the state, whether the murders involve police or civilians. Unlike such directors as Sofia Coppola, who would rather erase race from her work instead of either rising to the challenge of telling a complete story or choosing a different topic that is less likely to involve race, Bigelow was willing to use her hard won fame and expertise to tackle a difficult subject that is sadly still unfolding in the same way half a century later. She deserves credit for getting out of her comfort zone. Unlike well-established directors such as Steven Spielberg, it is still not easy for her to get the green light from movie studios. From the movie executives’ perspective and considering the political climate, she is taking a risk.

Compared to all films made in the past year, Detroit is a solid, substantial contender. In terms of Bigelow’s oeuvre, Detroit is one of her weaker films, but for me, more memorable than The Hurt Locker, The Weight of Water or The Loveless. In terms of films that tackle race in the US in the past year, Detroit is not worthy to touch the hem of most of those films, including I Am Not Your Negro, which is surprising. Bigelow has already succeeded at making a film about race in America, Strange Days, a gritty sci-fi apocalyptic masterpiece for the US, which only averts doom and destruction when the authorities are finally willing to listen to the least of these instead of protecting the worst of their brothers in blue.

I think that Bigelow became overwhelmed at the scope of history. Instead of following her solid narrative instincts of finding a real life main character that corresponds to her fictional main character staple, an outsider insider, i.e. a person whom she could empathize with, and following that person’s development to gradually tell a broader story, Detroit gives a substantial amount of historical background and context before narrowing the focus of the story to follow a large number of characters in a specific location, the Algiers Motel. I did not know that there was a black woman forensics investigator who investigated the extrajudicial executions at the motel, but Bigelow could have used that investigator as a way to tell all aspects of the story without the story feeling as scattered. Bigelow loves investigations and discovering things, but instead, her film is a recreation, not a revelation or a journey like most of her films. The only suspense is who would die and when, and Bigelow is not a horror filmmaker. Horror is not her forte, but Detroit would have been more effective as a horror movie for black people. There are several moments that convey how quickly a black person can go from an upstanding citizen to victim: during the bus evacuation scene, when John Boyega’s character is brought in for questioning without his uniform and when two men try to escape the death squads at the motel.

There are only two moments when I felt like Bigelow felt connected to the story. The first moment is when one of the cops hits a white woman and says, “I’m trying to protect you.” The second moment is when a cop demands that the victims see nothing and keep quiet. Bigelow’s Detroit is her response to the world: I see what you did, and it matters. You are not what you claim to be-protectors.

Just because Bigelow’s intent is to depict the authorities’ actions negatively, did she effectively convey injustice to the viewers by providing context to the Detroit Rebellion or would the viewers just see a riot? I’m not sure. Unfortunately I was plagued by doubts early in the film. Even after the first daylight extrajudicial killing and the first nighttime extrajudicial killing at the motel, viewers could still rationalize why those two men deserved to die based on how they were depicted before the shooting. I don’t think that Bigelow was trying to give moral wiggle room to the viewers, but I think that it is still there. Unlike Fruitvale Station, Bigelow is more interested in the frenetic pace of chaotic cinema to capture the insanity of that night, not character development of any individual. She expects too much from her audience. She thinks that because a man is shot in the back while holding a bag of groceries and is aided by an elderly woman to say his final words to his family that her viewers will sympathize with him. Bigelow assumes a level of empathy from her viewers to human beings who happen to be black. Unfortunately hundreds of years of history, including the events surrounding the Algiers Motel incident suggest otherwise.

Detroit is characteristic of Bigelow’s desire to show us an unflinching view of the ugly parts of life. She effectively depicts the moral abdication by the National Guard and the Michigan State Police then condemns the judicial system for retroactively vindicating and replicating the psychological brutality of that fateful evening. She implies by filling the courtroom with other cops showing support to the defendants that the brutality and intimidation will continue. This film is her least optimistic film because she shows how hollow it is to reassure the victims that the Algiers Motel incident is an isolated one. The most outgoing character transforms from a person who happily interacts with anyone regardless of race to someone who is so traumatized that he shuns all contact with white people even if there is a monetary incentive. His isolation is rooted in trauma, but he is also withholding his favor: he will never sing for them again after he was forced to sing under duress. Bigelow responds to #NotAll with #YesAll because nothing has been done to prevent it from happening again. She condemns herself.

Detroit simultaneously tries to be a snapshot of a particular point in a whirlwind of chaos and a comprehensive historical summary, which means that it ultimately fails to satisfy. It is a long movie, but it curiously leaves a lot out. Why didn’t we get to go into the morgue to figure out which victim was that man’s son? Why did Carl remind me of Lafayette from True Blood-intentional or not? Why didn’t anyone mention the toy gun during the brutal interrogation? Why didn’t the cops find it? Why did she pull punches on the sexual assault and make it seem more accidental? Why was Boyega’s character there at all? He didn’t give these cops coffee so why were they cool with him just hanging out? If she was trying to make him into a Schindler figure, it did not work. Instead it felt like she did not get the complete story. If ever a movie needed to end with a juxtaposition of the actors with the real life people, it was this one.

Detroit’s main weakness may be its source material. The filmmakers investigated the incident instead of getting the rights to and adapting a nonfiction historical book that already researched the event. I felt like the movie left a lot of unanswered questions, and I plan to eventually go to the library to find out what is missing. I applaud Bigelow’s noble and ambitious effort, but instead of feeling overwhelmed and condemned, she should either not try to reinvent the wheel or cling to her narrative staples.