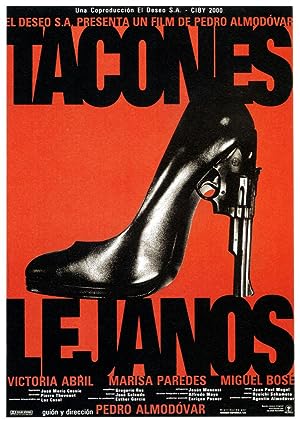

Pedro Almodovar is one of the greatest living film directors, the rightful heir to Hitchcock’s throne with his mix of psychosexual driven dramas and an innovative storyteller who delivers uniquely crafted narratives. When Hulu notified me that his films were going to expire and be removed on June 20, 2017, I decided to watch all his films, including the ones that I already saw. This review is the seventeenth in an extended summer series that reflect on his films and contains spoilers.

High Heels is available on Amazon Video. I found it through my local library. I’ve seen it about three times. It is the most predictable of all of Almodovar’s films, but also possibly the most tragic since it is filled with unrequited love. No one gets the object of his/her affection, or if he/she does, it is not for long. There is no meeting of the minds. The whole film has an Oedipal/Electra complex with a same sex twist.

Every Almodovar movie asks the question of whether what we are watching is real or not? At the beginning of the film, we have to ask if any of the relationships are real or performances, particularly the relationship between the mother and daughter. The main character is Rebeca, the daughter, a twenty-seven year old woman in Chanel who is frozen at the emotional age of twelve when she killed her stepfather to preserve the one that she loves the most, her mother, Becky, who is an international icon. Rebeca is more like a jealous lover or a crazed fan than a daughter. She is in a silent, one-sided competition for and with her mother whom she has not seen in fifteen years. She marries her mother’s ex-boyfriend, a former journalist (think Talk to Her, but more of a sleaze) turned media mogul, got a job in the limelight as a news broadcaster to attract her mother’s attention and tries and fails to get closer to her mother upon her mother’s return to Spain from Mexico. She becomes friends with a local drag queen, Lethal, who imitates her mother’s pop phase, but has no real interest in getting to know her/him. She is barely able to suppress her rage at her mother’s self-centeredness and lack of interest, but pretends to be unconditionally cheery around her mother and suppresses her disappointment. She says that she loves her husband, but every interaction with her husband is hostile, and she shows indifference to mild annoyance at her husband’s infidelities. She only wants to be with her mother forever. She is a mad woman disinterested in any relationship except with her mother. If she could choose her mother and existed in the same world as Julieta, she could finally be happy.

Becky barely recognizes Rebeca, reacts dramatically at every juncture to overcompensate for her actual lack of thought, memory and concern over her daughter, preemptively acts angry at slights that she caused and is more apprehensive about how others see her. She performs as the loving mother, but has to be cajoled into visiting her daughter at Rebeca’s lowest point. She resumes her affair with her daughter’s husband. She only shares her genuine reactions to her employees and reveals to an investigator that she is scared of her daughter. If there were not hints throughout High Heels of her medical condition, I would theorize that she died after getting the flowers and note from her daughter that Rebeca wants to see Becky. The mean interpretation is that she spent her life trying to get away from her and can only escape her stalker daughter by dying and pretend to be the perfect, self-sacrificing mother before leaving her one last time. The kind interpretation is that she risks eternal damnation by lying on her deathbed to save her daughter.

High Heels’ preferred form of performance is the confession: of love, guilt, to a priest, to a policeman, on a deathbed. None of these confessions are completely true or function conventionally. The performer always leaves a crucial element out. These confessions cannot be trusted, and only the visual account of the film can be trusted, not the characters’ words. The most convincing performer within the movie is an investigator, who goes undercover as a drag queen or a drug addict and lives multiple lives while trying to solve crimes. As an investigator, Eduardo, he is not that good. He gets the description wrong. He fails to solve crimes even when the guilty party gives him the answer, which is reminiscent of What Have I Done to Deserve This? He reminded me of the Mother Superior in Dark Habits. He uses his cover to get what he wants, manipulates himself into people’s lives then uses his authority to keep it. He is just as much of a stalker as Benigno in Talk to Her or an appropriator as Angel in Bad Education. His initial sexual advances are unwanted and rapey though Rebeca later consents. He is just one in a long line of Almodovar’s depictions of ineffectual law enforcement. Real talk: his facial hair looked hella fake so I pegged him immediately. His cover is almost blown during a moment of serendipity when two women receive the wrong photos reminiscent of he situations in Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown. In the end, Manuel’s intolerant life is more sordid than the transsexuals that he denigrates. Both the investigator and Manuel make transsexual’s tragedy all about them, but no one, regardless of originating demographic, gets justice. Manuel’s gun is no match for Lethal’s.

In a gross way, Rebeca gets what she always wanted through Lethal—her mother’s love and attention. When Rebecca gets it, she rejects it and finally resembles her mother-uninterested in anything that does not personally benefit her and eager to get away. She becomes a performer to exploit his one-sided adoration so she can be absolved of any guilt. Unfortunately the consequences of this incestuous wish fulfillment lead to something that she never wanted. She is forced to give up her role as daughter and must assume the role of mother even if she ultimately rejects his offer of marriage. He wants to marry a woman who has killed at least two men (we never find out how her father died, but both Rebeca and Becky blamed him for keeping them apart, which we know is not true) and shows zero interest in him. She is pregnant by a man whose real name and personality is elusive even to his mother. Rebeca is finally forced to become an adult by becoming a mother and knowing that she no longer has one.

High Heels relies on Marisa Paredes’ iconic appearance to establish Becky’s fame. Paredes’ later performances in The Flower of My Secret and All About My Mother feel as if her fame transcends being contained in a single movie. Her performance references other icons such as Madonna, Marilyn Monroe and Marlene Dietrich. Becky can only live fully and well while performing, but is actually dying. In contrast, women who are physically well, such as Rebeca or the investigator’s mother, act like they are unwell. Rebeca, who has not been able to sleep since her mother left, and her stepfather rely on sleeping pills. Almodovar uses drugs, prescription and illegal, to hint at a character’s inability to live well despite seemingly having everything. The medical profession has ultimately failed to improve anyone’s life.

High Heels only has one depicted incident of illegal drug use. There is a lesbian couple in prison. One of the women resembles Lethal, is the only genuine transgender woman in the film and purposely gets thrown in jail so she can be with her lover then is outraged that her lover would risk their happiness by taking drugs and possibly harming herself. This relationship parallels the investigator’s outrage at Rebeca confessing to murder, which will possibly keep them apart and endanger his happiness. Rebeca’s addiction to her mother is as dangerous as any drug. Her problem is that all she does is “think of me.”

Almodovar repeatedly uses basketball during transition from the outside world to jail, a transition which he also used in Live Flesh. There is a blink and miss it cameo by a young Javier Bardem, and the character is named Javier. We finally get to see a couple of black women. They are inmates, thieves and drug dealers. Hurrah…….The Midwife paid homage to High Heels, especially the idea of returning home when dying, the janitor parents and childhood home in a basement and the difficult mother daughter relationship. The opening scenes in the airport are most reminiscent of Hitchcock’s style as Rebeca waits to greet her mother.

High Heels may be predictable for an Almodovar film, but perfect communion is brief and impossible to sustain. Wish fulfillment always comes with a catch that threatens to destroy what you love or obliterate your identity. Love is madness inappropriate, suffocating and excessive. The saddest part to me is that Rebeca’s most honest relationship, her burgeoning friendship with a social worker based on shared heartbreak and happenstance, cannot continue without destroying Ernesto. Everyone is alone.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.