Pedro Almodovar is one of the greatest living film directors, the rightful heir to Hitchcock’s throne with his mix of psychosexual driven dramas and an innovative storyteller who delivers uniquely crafted narratives. When Hulu notified me that his films were going to expire and be removed on June 20, 2017, I decided to watch all his films, including the ones that I already saw. This review is the sixteenth in a summer series that reflect on his films and contains spoilers.

I’m not Catholic. I can’t speak Spanish. I’m unfamiliar with Spanish culture and history because I’m an American. Dark Habits was the hardest Almodovar film to wrap my head around to date (there are only four of his films that I have not seen yet), but I was undeterred and watched it three times. Afterwards I discovered there were lost in translation problems, which I can attest to because the final denouement song has no subtitles and clearly something important is being communicated on multiple levels. Almodovar is not a fan of this film because he did not have complete control of the film and bowed to certain commercial considerations in casting, which resulted in him having to change the storyline and may have inspired Broken Embraces to a small degree.

As a viewer, I have to concur with Almodovar’s assessment. Unlike his other films which may be initially confusing at the beginning of the film, but by the end, a viewer can see how Almodovar always had complete control over all the threads in his storyline then brought them together in a perfect bow, this film feels unwieldy throughout. There is no true central character. After the first two viewings, there did not seem to be a central storyline, but multiple ones like a truly provocative extended episode of Transparent, the Catholic edition, with special guest director and writer Almodovar, but after the third viewing, I would suggest that the central story is the fate of the Community of Humble Redeemers, which is lacking in funds, bureaucratic support and hemorrhaging members. Dark Habits could be Almodovar’s spin on notable nuns such as Hildegard von Bingen although his singing nuns are quite scandalous.

Dark Habits commences with Yolanda, a former botany teacher turned nightclub singer who hides from the cops in the Community of Humble Redeemers. Cristina Sanchez Pascual plays Yolanda, and while Almodovar bemoaned her acting ability, she certainly had a flare for wearing shirts that are open to the navel and seeming stylish. There is also a hilarious scene where she discusses her academic past and automatically crosses her leg while lifting the hem of her skirt to smoke. I’ll take their word that she could not act, but that woman would have made J Lo jealous. Just get her some conditioner for her hair, but that look was cool then. Pascual knew how to show skin, which would leave most women feeling self conscious or awkward.

There are five nuns, including the Mother Superior, who is her biggest fan and instead of saints has her office decorated with posters of beautiful famous women. The other four nuns are also quirky. The Mother Superior’s contemporary is a secret romantic novelist and is ready to jump ship. She is sick of penance and wants to live. One has more in common with Saint Francis and is addicted to cleaning. Another is a former murderer and masochist or a mortification zealot. The last one loves fashion and is unaware that she has a work husband, the chain-smoking priest. Yolanda ends up being the least interesting character on screen, and I am including small supporting characters such as the Mother Superior’s drug dealer and the Marquise, who looks like she belongs in Terry Gilliam’s Brazil.

The saving the orphanage trope usually works because a viewer can understand why the charity is essential to others, but I felt ambivalent towards this nunnery’s mission. On one hand, it is a sanctuary, a refuge, a place without judgment for the women who are not nuns, but on the other hand, the Mother Superior is deceiving the church and all but one nun and is using her position and the nunnery’s resources to score drugs and chicks while using salvation vernacular. Because Almodovar usually treats madness induced by love sympathetically, I did not automatically judge her. Throughout Dark Habits, the Mother Superior lavishes Yolanda with attention, gifts and drugs, but the second that the Marquise arrives, Yolanda does not hesitate to help her and work against the Mother Superior, which initially surprised me considering that she did not really know the Marquise, and the Mother Superior spent more time with her until I recalled an earlier detail.

The Marquise refuses to financially support the convent, not only because she is grotesquely selfish. She sees the convent as a prison for her daughter and her, a tool used by her deceased husband to control their behavior and keep them sequestered from the world with a veneer of piousness. The Mother Superior excuses his behavior as strict whereas her contemporary, Sister Rat, does not. The Marquise has positive interactions with the other nuns. The Mother Superior’s constant surveillance of Sister Rat, the one person that threatens her control, indicates that while the convent provides a certain freedom from the law of men, it is another type of cell. Another sign was when the Mother Superior discourages Yolanda from quitting drugs then happily offers them to her after she has done so. From the outside world, the Mother Superior and Yolanda look like they are in adjoining jail cells talking through the window. The Mother Superior just has a prettier face than the priest in Bad Education and Law of Desire, but they are both vampires out to capture the songbird.

Yolanda and all the nuns but one leaves the convent and the Mother Superior either to live in the real world or a more traditional, restrictive life in another convent. This mass departure and rejection indicates that while Almodovar does not judge the Mother Superior for her exploitation or madness, he does not agree with it either. When Yolanda arrives, she is depicted two times with a halo-either backlit from the sun or because of her placement in front of a painting of a saint. The Mother Superior thinks that Yolanda is her last hope to keep the convent alive, but she is the last hope to wake up the nuns and discover their real identities. When Yolanda arrives, she is afraid and hunted, but she leaves without fear of reprisal and urges Sister Rat to abandon her mission and come with her into the unknown along with the Marquise. They choose adventure and self-fulfillment. The nun and the priest go full Thorn Birds. Sister Francis sadly leaves her animals in the couple’s care to go to the new convent. Only the masochist and the Mother Superior are together, initially determined to create their own order, but in shock and grief to discover that they are alone.

There is the idea that if fallen women seek sanctuary from the convent then become nuns, they may not fully change, but they should be fully accepted, which is a laudable Christian idea. For me, the danger is when acceptance is actually exploitation, and I think that Dark Habits agrees. The Mother Superior has characterized her unrequited carnal madness as spiritual devotion as shown in the scene where she treats a napkin that she uses to remove Yolanda’s makeup as the Shroud of Turin. Being alone is her wake up call-the convent will die.

While Almodovar does not judge drug users in his films, drug use is seen as self-medicating against reality. The masochist nun drops acid to have “visions.” The Mother Superior is a heroin addict who hates soft drugs, sold all the reliquaries to support her habit and is going to fund her new order by becoming a drug mule. Yolanda stops using drugs once she is ready to live a life free from the prison of her destructive love affair and has no desire to start a new one. The Community of Humble Redeemers is a nice place to find yourself away from the punishing male gaze, but it is a horrible place to stay and become exploited by female predators for your money or your body.

Dark Habits revisits the idea of who owns stories. Sister Rat takes the stories of the women who seek refuge in their convent and writes romance novels, but purely for the joy of writing. Her sister takes the proceeds and insults her sister to insure that she can continue to take the profits. The Mother Superior is horrified by this violation and comes down hard on Sister Rat, which seems rich considering her extracurricular activities. Almodovar does not seem to see Sister Rat’s act as a violation, but vindicates it with outside validation of praise.

Dark Habits is the rare film where a lesbian gets center stage although she is an exploitive one. There are no transgender characters. The role of law enforcement is depicted as ineffective, male and punitive with no desire to actually discover the truth, but to humiliate and judge like in Law of Desire. Comparatively, adjacent to Mother Superior, she does seem like a reasonable and compassionate choice as opposed to falling on their mercy.

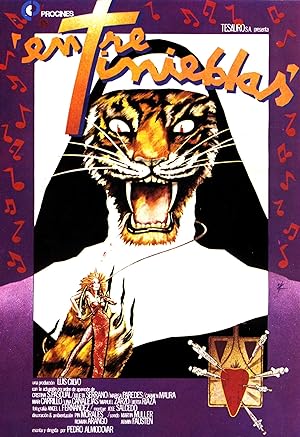

I have already covered many of Dark Habits’ flaws, but it actually has some cringe worthy moments if you did not run away at the prospect of a drug dealing nun. Characters casually reference missionary work in Africa, the entire continent, not a particular country. To make matters worst, they blame cannibals for the death of one nun, which is an inaccurate propaganda tool used since colonial times by Spain, specifically the court of Queen Isabella to enslave people. I hope that Almodovar inadvertently used a racist trope out of ignorance, not malice. He also threw in the Tarzan legend without explicitly referencing the Edgar Rice Burrough’s tale as a plot twist. Tsk tsk tsk. I also don’t think tigers come from Africa.

Before watching Dark Habits, I would highly recommend that you watch Live Flesh, The Flower of My Secret and Bad Education. This film feels like a rough draft for those three films. I do not think that this film is required viewing except for the most ardent Almodovar fans because of its problematic narrative and provocative subject matter. Almodovar lovers will be thrilled that most of his iconic actors, Carmen Maura, Marisa Paredes, Chus Lampreave, Julieta Serrano and Cecilia Roth, are in this single film. Side note: I hope that the kitten was immediately adopted by someone and did not touch the syringe.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.