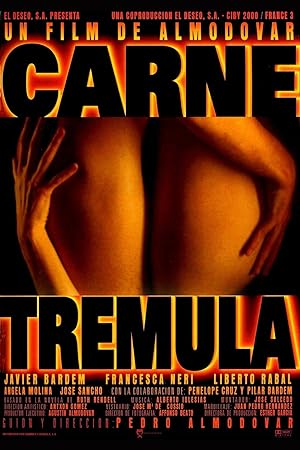

Pedro Almodovar is one of the greatest living film directors, the rightful heir to Hitchcock’s throne with his mix of psychosexual driven dramas and an innovative storyteller who delivers uniquely crafted narratives. When Hulu notified me that his films were going to expire and be removed on June 20, 2017, I decided to watch all his films, including the ones that I already saw. This review is the fifteenth in a summer series that reflect on his films and contains spoilers.

I am unfamiliar with Spain’s history, but Live Flesh struck me as a beautiful story and a parable about the struggle for Spain and Europe’s soul. I first saw the film in 2011 on Netflix then saw it two times this year soon after my Hulu marathon. I do not think that I have ever written two reviews on a movie before now, but a more in depth one is warranted for such a complex film. This interpretation of Live Flesh benefits from repeat viewings. When I initially saw the film and did not know how it was going to unfold, my view of the characters was dramatically different. For Almodovar fans, I think that the meaning of this movie is revealed more if you have already seen Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, Dark Habits, Matador and What Have I Done to Deserve This?, but for acolytes, these movies are weaker than Live Flesh, which stands perfectly on its own so don’t feel the need to do any homework before watching it.

Live Flesh’s narrative is linear and has five separate time jumps: 1970, 1990, 1992, 1994, and 1996. The majority of the movie unfolds in 1990 and 1994. There are five major characters: Victor, the unlikely savior who would have been played by Antonio Banderas if he was younger and available in my opinion; Elena, an Italian diplomat’s daughter who resembles Michelle Pfeiffer and has amazing green eyes; David, a cop and athlete played by (the hot) Javier Bardem; Sancho, his partner; and Clara, Sancho’s wife.

Live Flesh is Almodovar’s secular, not blasphemous, take on the Nativity Story, but instead of setting it in Bethlehem, he sets it in a desolate Madrid during a state of emergency during the Franco regime, i.e. when Spain was like Roman occupied Palestine/Israel paralyzed by fear and fascism. Instead of a virgin, a young prostitute played by Penelope Cruz gives birth to the savior of Madrid, Victor. There is no Joseph, but an older woman who runs the brothel and is experienced in this kind of labor (played by Javier Bardem’s mother). Christmas lights in star shapes decorating the empty city streets replace the star of Bethlehem. Instead of a manger, he is born in a bus because there is no other way to get to the hospital when there is a curfew, and the state has suspended all freedoms, including the right for groups to gather and habeas corpus. His birth is simultaneously praised and problematic for the government. He and his mother are awarded free bus transport for life.

Victor is not a typical Jesus figure. His love is definitely carnal, not spiritual; however it is pure and naïve, bordering on stupid. He becomes the focal point to free the other characters from the sins of the abusive authoritarian state as symbolized by the cops and their dysfunctional romantic relationships and to remove the self-condemnation and guilt of Italy’s role in Spain’s descent into fascism. He is categorized as a criminal to cover up the crimes of those in authority that feign camaraderie, but actually hate each other. He spends time in the wilderness, four years in jail and his neighborhood, which is in ruins. He is proud of not taking drugs, embraces children, is skilled with his hands, has original interpretations of the Bible, particularly the curse section of Deuteronomy 28 and Genesis and is even shown carrying fish. Only through truth and reconciliation can Spain and Italy move forward and away from the destructive legacy of the past and give birth to a hopeful, vibrant and free future.

Elena is the symbol of Italy’s next generation, prosperous, but crippled by guilt over the sins of her father and desperately trying to expatiate that guilt through self medicating or donating her life, time and money. Like Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, she rejects Victor, but not out of forgetfulness, but dissatisfaction. Victor’s virility is ridiculed like Matador’s Banderas’ character. Instead she is attracted to Bardem’s character (duh), a midpoint between the fascist Spain of the past as symbolized by Sancho and the more sensitive Spain of the future as symbolized by Victor.

Victor is the next generation that must choose between accepting or rejecting the legacy of authoritarianism as symbolized by his partner, Sancho. In a sense, history repeats itself. Italy prefers the next generation’s version of the strong man, but because the strong man favors jealousy, possession, deception and vengeance over truth, he is literally and figuratively crippled and prevented from literally having a fully consummated future. He can only have oral sex so Elena cannot have children, but she wants them. Even though he probably knows about her past addiction to drugs, he encourages her to smoke a joint with him. He does not want her to see clearly, but he claims that he is doing it to relax. He goes from a reasonable enforcer of the law who rejects the brutality of his partner to embracing it while trying to maintain a reasonable veneer as the pride of Spain, a famous athlete.

Sancho is a symbol of the last generation that fully embraced the authoritarian government. He is an alcoholic, a jealous and abusive husband, a bad cop who resents everyone around him and confuses love with possession and terror. His wife is another symbol of Spain, those who experienced and survived the terror of the authoritarian regime, but are still suffering under its remnants. The most odd part of the film is how the only parental relationship, between mother and son, is never again depicted except through words after the opening sequence. She clearly loves him and provides for him, but his interactions with Clara are more like a mother figure than a love interest as he eagerly shows her his health report card and looks to her for guidance.

Clara passes on the more positive legacy of Spain to Victor by helping him create a home and teaching him sex positivity and the dynamic of a healthy relationship. She rejects Sancho, but cannot escape him until she finds the courage to fight him in order to save the next generation, Victor, which she could not do for David, and no longer fears repercussions even in the face of death. Their final scene is the visual antonym to the final scene in Matador. Their death is necessary for Spain to enjoy freedom from terror and destruction.

David embraces Sancho’s violent legacy when he realizes that their relationship is based on her guilt and is an act of charity. He ends in self-imposed exile in a new world, America, and admits his guilt, which frees Victor and Elena to finally be together in a new vibrant Spain during Christmas as they expect a child, the future of a new Europe free from terror and filled with joy.

Live Flesh’s madness is superficially rooted in love. Victor initially reminded me of Benigno in Talk to Her, but repeat viewings made me realize that he was a less problematic, more stupid Ricky in Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! Dude, stop picking up guns and being around people who tell you to go away. You don’t know her well enough to stage an intervention. Sancho is a madman in love, and David later transforms into him when Victor reappears and threatens his relationship with Elena, but upon repeat viewings, I believe their madness is rooted in power, not love. They want the power to kill without consequence, to eliminate competition and possess/dominate others by force if necessary. Their madness is a microcosm of the state’s madness, autocratic rule. Usually Almodovar uses police to reveal the intrusiveness and ineffectiveness of the state, but in this film, their role is way more sinister. The medical community, which is usually an ally, a villain or a complete failure, is largely absent as people are forced to tend to their own medical needs or appear only as a photo op. I am unaware of any members of the LGTBQ community in the film, which is unusual for an Almodovar film. There are plenty of black people in the street scenes.

Live Flesh features some of Almodovar’s best directing, particularly during the 1970 and 1990 sequences and the climatic denouement. In the first sequence, visually, he follows the logic of the sound-what one person hears we subsequently see. The 1990 sequence is very reminiscent of Hitchcock. In the denouement, Almodovar tips the camera so David and Sancho are on the same level although Sancho is standing and David is in a wheelchair. It symbolizes their distorted view of the world and signals that David finally sees eye to eye with Sancho. They are equals. There is an amazing seamless transition from Elena looking at the surveillance photos to the former partners looking at them.

Live Flesh is the first film in which basketball plays a crucial role in an Almodovar film. (The second film is Julieta.) Other than bullfighting, Almodovar’s films are generally sports free. I think that he was visually interested in the net and kept framing David in it perhaps as a symbol of his deception, omissions about the past from Helena or to show that even as vibrant as he appears to be, he is trapped and stuck like a spider. There is one humorous moment when we see that it is possible for Victor and David to find common ground when they become distracted from their animosity by a goal in soccer. It is a brief, but fleeting moment of joy. For Almodovar, sports do not provide fulfillment or long-term peace.

Live Flesh is an underrated Almodovar classic that pulls together numerous past cinematic threads in a single perfect work of art. It is one of his most sensual and political films, a successful work of resistance and redemption that only Almodovar could imagine. I highly recommend it, but there is plenty of nudity and sexual situations.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.