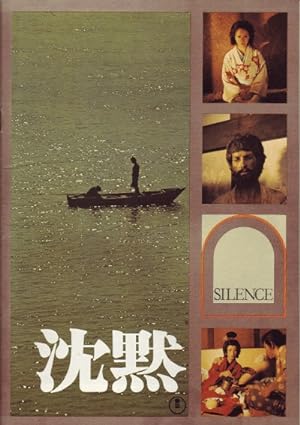

Chinmoku, which is the Japanese word for Silence, is the first adaptation of Shusaku Endo’s book, which Martin Scorsese recently adapted. Chinmoku is allegedly not as faithful an adaptation of the book as Scorsese’s Silence, but I still preferred it and plan to read the book. For those potential viewers unfamiliar with the book or the films, Chinmoku is about two Portuguese priests in seventeenth century Japan when Japan outlawed Christianity.

Scorsese’s Silence leans more towards films like Heart of Darkness and Apocalypse Now where a young man seeks an older man who is more of a legend then is changed by the journey. Chinmoku took a more universal approach in its depiction of how human beings’ ideals and imagination potentially can crumble in the face of actual suffering regardless of whether you are a peasant, a prostitute or a priest. Even the dissonance of the soundtrack communicated the culture clash and made Chinmoku feel more like a horror movie in the vein of John Carpenter’s Halloween. We get a sense of what life is like without persecution, and people tell harrowing stories of persecution, but the horror develops gradually before life and identity are completely disrupted. There are no monsters. Each character is potentially the monster, and the horror is the realization of your own weakness and inadequacies.

I did not completely understand the significance, but red kimonos seemed to symbolize the destruction of the ideal self in the face of suffering. Even though I watched Chinmoku on YouTube, and the picture quality is far inferior to the high definition quality of Scorsese’s Silence, I was more struck by the use of color and composition in Chinmoku. Chinmoku depicts the priests as helpless when they are not cared for by the locals. When the village is executed, the priest deliriously puts on a red kimono while stumbling through the carnage for food and water. Later a man, maybe a shaman, in a mask and a red kimono dances in a ritualistic fashion after the priest is captured.

Chinmoku’s character development makes more sense. Kichijiro is depicted as a man trying to regain favor with his community. The actual priests are only a means to an end for him, which explains why he would repeatedly help and betray them. The priests speak Japanese. The peasants protect the priests literally and spiritually by withholding information about their predecessor. Ferreira is also shown as more desperate and eager to flip the priest. All the Japanese officials who torture the priests and peasants are former Christians. Even though Scorsese’s Silence extensively talks about the vulnerability to torture as a witness and the inability to look away, Chinmoku effectively shows it, particularly when a husband and wife are being persecuted. This persecution is endemic to Christianity, a natural negative consequence when Christ’s ideals meet and fail to transform the flesh, not something found outside of Christianity, which I think is more provocative than Scorsese’s ideas of what it really means to be Christlike.

Chinmoku actually reveals what it is like to be the wife of one man then assigned to another who also takes your husband’s identity. Women are given more central roles as witnesses and victims of torture than in Scorsese’s Silence. The wife is the most interesting character in Chinmoku even though she is only a minor character. The final scene when she is initially welcoming and hopeful because her new husband is someone who showed her kindness in the past then, if put delicately, is ravaged, is more in keeping with the bleak confrontation of moral character and the random fortune of when you exist. (Side note: the author actually hated what I loved about Chinmoku.) Chinmoku’s prologue introduces the concept of the gun and the church, fairly depicts the earnest missionary work and belief of the peasants then wordlessly reminds us that in the absence of Jesus, only force and violence remains.

Chinmoku is a haunting depiction of how untried spirituality can result in another type of slavery when our natural desires for food, water, sex and life are manipulated and transformed into something monstrous by the desire for power over another in the guise of philosophical debate.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.