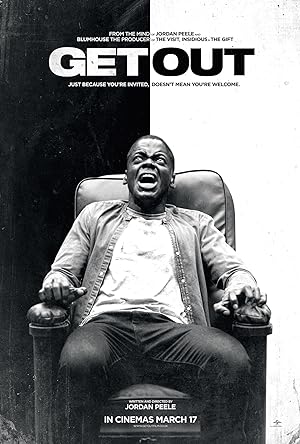

Get Out is a must see film that takes conventional horror film plots and reassembles them to create a fresh, subversive perspective from the point of view of the protagonist, a black male photographer, who goes upstate to meet his girlfriend’s parents. Jordan Peele, a biracial black comedian, directs Get Out in his directorial debut.

There have been so many think pieces about Get Out that it almost feels redundant to try and write anything about the film so I will do my best not to repeat anything that I have read elsewhere. I am writing as a biracial black woman from New York City who has watched too many films.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

Theaters should have double features showing I Am Not Your Negro and Get Out. For the most part, Get Out represented the way that the world felt to me. I have always felt more comfortable in the city than the suburbs because I am more visible in the suburbs and thus a target so the opening scene resonated with me. The opening scene reminded me of Trayvon Martin walking in his neighborhood with some guy following and attacking him. When the man’s body goes limp, he is as good as dead. Get Out shows viewers something that the majority of Americans cannot see: black people as vulnerable victims with a right to defend themselves regardless of the race or gender of their attacker and white attackers as monsters, not victims. In reality, the majority of Americans will judge the victim as guilty even when self-defense is not an issue. An unarmed black man is still seen as a weapon, and Get Out refutes that notion. Get Out then claims the right of the survivor for black victims: vengeance.

Get Out represents the world as it is. Get Out depicts the paranoia felt by black victims before events reveal that this paranoia is rooted in reality. James Baldwin makes two assertions: that black people are robbed of everything, including their artists, and the “social terror, which was not the paranoia of my mind.” Baldwin says, “You want me to take an act of faith on some idealism of America that I have never seen.” Get Out makes the victim a photographer, someone whose gift is having a perspective different from most people. The victim of Get Out tacitly cosigns this system when he constantly suppresses that gift to “reassure white people that they are not hated and done nothing of which to be hated.” He participates in the liberal fantasy that Baldwin speaks of in his analysis of The Defiant Ones. The definition of a sociopath is that the sociopath makes you apologize for the sociopath hurting you. We rob ourselves by dismissing our perspective as paranoid and trying to pretend that our social terror is not based in fact in order to assuage our attackers.

Get Out also illustrates Baldwin’s assertion that “our presence is disruptive.” Whenever Chris tries to interact with other black people, it is always cut short or outted. Whenever the victim appears, people are friendly, but in a weird, possessive and obtrusive way. I have been there when people randomly ask you about your thoughts on tap dancing when you have never danced with tap shoes in your life. You want to believe that it is just another awkward social interaction, but the comments are usually rooted in race. Why are you telling me about Jesse Owens or Tiger Woods? Do you usually say “my man” or “thang?” Is it appropriate to talk about my sexual prowess when I just met you?

The most heartbreaking aspect is when Get Out depicts the relief of finding a normal person to relate to, but you later discover is just as bad as the others. The brilliant Stephen Root is like an oasis of normality. He relates to Chris about something he actually cares about: art. He is empathetic about Chris’ awkward interactions and dismisses the other guests as ignorant, but this art dealer is actually the worst. He literally covets Chris’ eyes. Get Out illustrates the feeling that black people have on a daily basis. People want the fruits of black labor while dismissing the idea that we have a brain or a unique experience that produces that work. He does not think that Chris’ talent is a part of Chris’ soul, but it is something innate in his biology, his eyes, and by taking his eyes, the art dealer will acquire that talent when in reality, if the transfer did occur, the art dealer’s photographs would be just as crap as they were before. His blindness is emblematic of what Baldwin calls American blindness or cowardice—a failure to truly confront the differences in American experiences. He rationalizes that he is different while being guilty of the same exact crime. The art dealer is emblematic of the “lie of pretended humanism.” You are not different just because you voted for Obama.

Get Out’s moral monsters believe a fictional fantasy also confronted in Hidden Figures: the inability to admit that black people can be excellent without dismissing or minimizing their contributions to work. They can’t admit that their failures are their failures so they rationalize away our talent. They want to steal everything from us, and they want us to sit back and enjoy the show while rationalizing that it is merciful and not monstrous. Get Out’s most original concept is the idea of the sunken place, a dissociative state that many rape victims experience and which visually resembles what happened to many kidnapped black people during the Middle Passage-they drowned because they were thrown over board, or death was the only way to escape.

Because I saw The Skeleton Key, I immediately knew what the twist was, especially when the father mentions his mother, and the next shot shows Georgina in the kitchen. I appreciated that there was a scientific, not supernatural, explanation since this echoes the historical (and probably ongoing) reality of medical experiments on black bodies. I guess that a side effect of the procedure is an inability to sleep. I also knew that Rose was evil because she killed a deer and was totally fine.

While I related to many aspects of Get Out, I still experienced moments of dissonance. Get Out depicts, but does not necessarily cosign Chris’ problematic relationship with black women. Georgina is a crazy bitch (she is), but the mother who raped your mind is great because you don’t want to smoke. He is literally betrayed by his white girlfriend at every moment, but will rationalize away the signs or make excuses until it is almost too late. Chris gives white women the benefit of the doubt and assumes the worst about black women’s motives. Black guys experience solidarity (Rod!), but black women are either depicted as the enemy with suspect motives (problem with black men dating white women) or betray black men (hurrah, Erika Alexander got work) by not believing them and ridiculing them. Get Out seems to be saying that black women are complicit in creating a system that victimizes black men without fully recognizing that black women are also victims of this system or hopefully it is depicting that mindset and implicitly condemning it. Yes, Get Out retroactively makes audiences realize that Georgina’s black soul is impressive because she is the only one that tries to break free and communicate without the aid of a camera flash, but we never get to see her, which is what was most disappointing for me. I’m not entirely comfortable with my seat at this table because some of it feels like the same victim blaming that Get Out tries to break out of. Get Out seems to see black women as a problem or an obstacle, not fellow victims. Get Out makes us encourage the hero to leave the black woman behind. While intellectually I agree because she is no longer in control of her body, it does not sit well with me.

I will admit that because I love Catherine Keener, it was weird to be innately happy to see her and intellectually root against her. Allison Williams did a perfect job and deserves to graduate from TV’s Girls. Caleb Landry Jones did not do a great job. His accent kept shifting-is it Southern or New York? What are you doing? The aggression worked, but this was not one of Jones’ better performances (see Byzantium).

Get Out is a terrific directorial debut for Peele, and I look forward to his next social commentary horror movie.

Stay In The Know

Join my mailing list to get updates about recent reviews, upcoming speaking engagements, and film news.