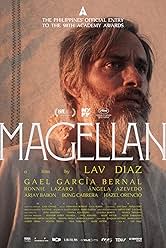

“Magellan” (2025) is the Philippines’ submission to the 2026 Oscars “Best International Feature” category and chronicles the sixteenth century Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan as he travels from Malacca, which is now known as Malaysia, for the Portuguese king, returns home to Lisboa to recover from the expedition, marry and get approval for the next one, goes to Spain for funding then travels the Pacific Ocean until he reaches Cebu, which is in the Philippines. Writer and director Lav Diaz makes his first non-Tagalog language film starring Gael García Bernal as the titular explorer and Amado Arjay Babon as Enrique de Malacca, a man that Magellan purchased and is possibly the first person to circumnavigate the globe albeit against his will. With a challenging runtime of two hours forty minutes, the lemon is worth the squeeze as a slow burn, first-hand vicarious experience of colonizing, which becomes an anti-colonialist film without deviating from history. If you want to see this movie, do yourself a favor and see it in theaters because watching it on the small screen probably makes it harder to appreciate and understand what is going on.

Diaz has the composition skills of a painter with the narrative filmmaking style of a documentarian. Other than a brief flash of the year and place where events are taking place, there are not a lot of context clues other than the sparse dialogue. Moviegoers who come to “Magellan” with a wealth of knowledge about him, the locations, the era and the power dynamics will have an advantage. Those without will need to pay close attention and just go with the flow for context clues. When there is dialogue, it directs the audience to the characters’ motivation with the sparsest reference to fellow characters’ names and never a glimpse of the real movers and shakers such as the ruling class. Diaz is more interested in focusing on the action of how things happened, not making a sumptuous costume drama. Diaz sets a camera up with the characters moving in and out of the frame before cutting. It is often staged like a play though the acting style is naturalistic, not theatrical. On a small screen, in long shots, it is harder to distinguish individuals because Diaz rarely focuses on a single character’s face except for Enrique, Magellan and Beatriz (Angela Azevedo), Magellan’s wife. There are mostly medium shots showing the character’s torso. Other characters are usually depicted in group settings. On a movie screen, the problem may still exist, but visually it would be easier to discern features.

If García Bernal was not so famous, it would be challenging to differentiate him from the other men in his crew without people occasionally addressing him by his first name. He learned Portuguese to play the role! His role is not necessarily the most important character in “Magellan,” but he does get the most screen time. The opening scene focuses on indigenous women beginning with one woman, Nafea (Yvanne Evangelista), in a river. Diaz focuses on her reaction, but not what or who she is reacting to. It is reminiscent of the Biblical tale of women witnessing the resurrection of Jesus Christ and running to tell others except it is the region’s indigenous practice, and they have mistaken the Portuguese’s appearance as the fulfillment of a prophecy. Watching is like stumbling into a lush Eden with naked people. Initially Diaz does not editorialize. He shows what life was like before and after the Europeans arrived then contrasts native Asian life with native European life before immersing the Europeans in nature and showing the process start again.

After Nafea’s announcement, later, masses of bodies are lying on the beach, including Magellan’s, and people in cages, including Enrique, are shown. Colonizing is not physically good even for the colonizer. Men are fall down drunk, sitting around bored or injured. At home, Magellan’s body is prematurely aged. Clad in black, women stand like rocks on the beach waiting for news of their husbands. It is only time with his healer wife that rejuvenates him enough to want to start the whole process again, and the dialogue gets heavy handed about the goals of these trips: religion, money and competition with other nations. The voyage reflects the limits of their alleged faith when weighed against other goals. Regardless of location, Magellan and his men’s life is about hunger, competition and misery. There is no joy. In the European portions of the film, daily life rarely shows men and women together in harmony though it does happen. When Magellan punishes crimes against nature, it is intriguing to see considering that the entire Western lifestyle seems like a crime against nature compared to the introduction to indigenous life.

If “Magelan” stands out, it is because Diaz also shows and celebrates the glories and flaws in indigenous life. He gets to do this because he is Filipino telling a Filipino tale, but ultimately, I defer to Filipino film critics regarding their stance on “Magellan.” He devotes a lot of time to depicting the religious practices of the indigenous in Malasia and the Philippines and devotes more time to the latter. The Babaylan (Sasa Cabalquinto), a shaman, engages in a practice that appears shocking even though Christian practice talks about blood, but does not use the literal substance in practice. In contrast with the Malaysians who used water, the Babayan’s tool is a signal to the audience that Magellan does not realize what he is getting into if he engages in a god battle for dominance and believes his present performance and success will guarantee future results. It is characteristic of Bible stories that God and gods will use men in a proxy war to show who is greater. Up to this point, Magellan and the European explorers are only concerned about Islam and carry an unspoken assumption that they can defeat any other god that crosses their path.

Here, Diaz’s pride in his people allows some creative indulgence in the folklore of the region as a determinative factor in fighting colonialism. It is also the first time that he shows a clash as it is unfolding instead of just the aftermath. There is also embedded a tale of Asian solidarity against invading European forces, an enslaved becoming the messenger to save people from his fate. “Magellan” is also a horror story complete with ghosts in the beautiful melancholy romance with death aesthetic that is part of the Spanish cultural heritage emblematic of Mexican filmmaker Guillermo del Toro and tales of vampire-like creature called a wak-wak. What is most intriguing about the wak-wak is how its description has more in common with Magellan and his men who leave bodies in their wake wherever they are, including their own.

Diaz could have improved “Magellan” if he had taken a page from Chan-wook Park’s “The Handmaiden” (2016) and used different colors for subtitles to illustrate when Portuguese, Spanish, Visayan and Cebuano were spoken. So much time is devoted to showing Magellan talking, Enrique interpreting then an indigenous person replying then reverse, repeat. It would have been more powerful to appreciate that process and contrast the meaning of words and how it changes depending on the language and the speaker.

If you are ready to set aside a considerable chunk of time to sample a contemporary example of slow cinema, then check out “Magellan” in theaters. At home, you will find it impossible to stay focused without interruptions. It is a more realistic take on the glossy, revenge focused anti-colonialist movies such as “RRR” (2022) and largely adheres to nothing but the facts. Diaz’s Filipino pride may not change the focus on the conqueror, but it does not pull punches when the conqueror gets conquered.