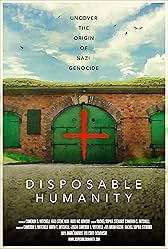

The family that films and research together, stays together. “Disposable Humanity” (2025) is a documentary that is part family road trip, part analysis of memorial spaces, part activist work for accessibility for disabled people in public spaces, and part chronicle of the Nazi’s secret extermination of disabled people program, Aktion T4. At an economical ninety-four minutes, the first hour is a tightly organized historical, institutional and personal account with the final half hour an ambitious, looser and personal story planted in the contemporary world reflecting on the past and its legacy in the present. Director and cowriter Cameron S. Mitchell partners with his dad, cowriter David T. Mitchell to make the unofficial sequel to “A World Without Bodies” (2007), a thirty-four minute documentary which his parents, David and Sharon L. Snyder, made.

“Disposable Humanity” is a participatory documentary, which is when filmmakers visibly and/or audibly participate in the narrative. The film exposes the logistics of making this film including transparency of how difficult it is as a disabled person to navigate public areas, including for spaces allegedly commemorating disabled people. Even though it is not explicitly stated, this continued insensitivity is a remnant of what inspired the Nazis and unintentionally continues their legacy despite the German people’s rigorous efforts to stamp it out of society. Cameron chooses to show how wheelchair users such as David and Emma Mitchell, Cameron’s sister, struggle to navigate these areas because of the lack of accommodations, which then need to be improvised if possible.

Apart from its main focus on historical atrocities, “Disposable Humanity” is essential viewing because it shows disabled people on vacation, thriving in families, having interests, being experts, etc. Disabled people can be marginalized in the media or only shown struggling, but in a documentary devoted to a group of people at a point in history when they are targets, the implicit antidote to and essential defeat of Nazism is for non-disabled people, an often temporary condition for most people, to proactively prioritize the comfort and center the existence of disabled people, especially those who cannot speak up. Snyder casually remarks that accommodations are possibly denied in Poland because of systemic efforts to make the area inhospitable to refugees, an unfortunate sign that xenophobia, just another branch in the hate tree, still exist. So the film becomes a contemporary account of progress proportional to how natural the family can enjoy public spaces.

“Disposable Humanity” also relies on conventional documentary narrative techniques such as showing archival film, which includes Nazi propaganda, montage of photographs and documents, and tours of the sites. The film also has the objective of establishing that the systemic murder of the disabled laid the groundwork for the Holocaust’s machinery, and it is a marriage between science and politicians, who then use war to disguise their (illegal even under Nazi German rule) abuse. It also details how in the immediate aftermath of World War II and memorials, disabled people’s plight rarely elicited outrage and was often the last to be honored in memorials. It is another sign of how disabled people are the canary in the coal mine when it comes to seeing signs that the broader public is in danger

“Disposable Humanity” predominantly interviews academic talking heads, which should not be conflated with a dispassionate, aloof, intellectual treatment of the subject. These researchers often passionately relate personal family history which is not explicitly credited as the reason for them joining a specific profession but is likely the reason. Other researchers are interested because of their disability. Even when reasons are not given, it is obvious that dedicated archeologists such as Barbara Schulz and Axel Dreischner had to fight to move away from archies and move their work to the field to unearth evidence. The narrative is structured with initially introducing an academic’s voice over establishing location shots of present-day images of the region, which are often bucolic, picturesque sites that show no visible indication of the horrors that took place then showing the academic in the space of the institution that they work in. The academics are frustrated at how people were reduced to almost nothing with no indication of the deceased’s personality, hopes and fears. It is because of their emotion that it fills in the holes that the homicidal bureaucracy left, including showing their personal possessions like a toy train.

When “Disposable Humanity” tries to branch out into analyzing memorial spaces, it needed to lay a better foundation for an audience unfamiliar with thinking about space and how information is presented in it. They show different examples of memorials, but it could have been established earlier what is the aggregate expected model before showing a more innovative, inclusive model. Side note: as a kid, I worked in a museum and became aware of how space is carved out within larger spaces to create exhibits so this is a huge interest that I have, which is why I got so aggravated when the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston moved its special exhibit space from the West Wing to a claustrophobic basement space that feels inhospitable to me. These are not instinctual subjects.

For example, David critiques institutionalization of disabled people as a link in the chain to the extermination of disabled people. It is unclear from just watching “Disposable Humanity” if he is innately or historically criticizing the practice. Later, it appears that it is something else altogether. Before it became complicit in euthanizing disabled people, Bernberg Memorial was (and still is) the site of a functioning psychiatric hospital and is one of six institutions that played such a role in World War II. Imagine if you are in genuine need of mental health care, and your only option is a place where people got tricked into believing they were getting medical exams before medical professionals killed them! It sounds like a recipe for paranoia and more psychological damage. It is entirely possible that David’s argument was more nuanced, but it is what was shown.

In addition, “Disposable Humanity” references work, including the parents’ documentary, as if there is an assumption that people should be familiar with it. Cameron could have taken a beat and mentioned that they were there before and why. Historical figures are addressed with their last name such as the propaganda director Schwanniger. It is not easily searchable online, but the answer is Hermann Schwenninger. Because this family is so immersed in the material, it is hard for them to consistently get people on the ground level and remember to introduce information as if it is the first time that it has ever been discussed. On the other hand, there is an implicit autobiographical tone to the film just inserted occasionally within the film like easter eggs such as the creation of his parents’ documentary likely was the beginning of Cameron’s interest in becoming a filmmaker when they bought the family’s first camcorder.

“Disposable Humanity” may seem like a traditional documentary, but it is more experimental that it appears. It feels as if it should be required viewing, especially at a time when global totalitarianism is gaining ground. The talking heads’ relief that though the US inspired Germany’s road to euthanasia, it did not make it, may need to be reevaluated considering events of Presidon’t’s second term.