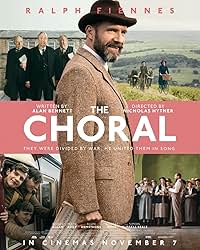

Set in 1916, smack dab in the middle of World War I, the Allies, the United Kingdom, France, Russia, Italy and Japan, are fighting the Central Powers, Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria. The little (fictional) town of Ramsden, Yorkshire in Britain is running out of men because they are all volunteering thus leaving the wounded, the old, and the young, who are just getting older and potentially eligible for the draft. When Gilbert Pollard (Thomas Howes), the usual choirmaster goes off to war, a choral society will have to find someone to replace him and replenish their choir’s numbers if they want to keep tradition. “The Choral” (2025) is another film in a long list of British films that tackles a serious subject, young people dying in war, then makes the concept palatable with an ensemble cast putting on a show, which provides momentum, and a tent pole thespian, Ralph Fiennes, in the lead to set the pace.

While no one will accuse “The Choral” of going at a breakneck pace, it covers a lot of archetypical characters in a short amount of time. Enough time is devoted to the last young three men in town to get invested in the sword of Damocles hanging over their head. Ellis is the girl crazy, revolutionary minded, working-class lad. Ellis’ friend, Lofty (Oliver Briscombe), is the lanky kid who delivers telegrams part time. Mitch (Shaun Thomas) enjoys spending his time at the pub. Bella (Emily Fairn) is struggling to remain faithful to her missing in action boyfriend, Clyde (Jacob Dudman). Mary Elspeth (Amara Okereke) volunteers with the Salvation Army and loves to sing. The society committee members are Herbert Trickett (Alun Armstrong), the undertaker; Alderman Bernard Duxbury (Roger Allam), who owns the local mill and is the local patron of the arts; Joe Fytton (Mark Addy), the photographer; and the vicar (Ron Cook). The two busybodies find Mrs. Bishop (Lyndsey Marshal) scandalous and shun her.

Because it is the war, everyone hates Germans, but the problem is that most music is German. While no one can deny his talent, the town finds their new choirmaster, Dr. Henry Guthrie (Fiennes), the local black sheep, scandalous for a variety of reasons, which includes being an atheist and a love for all things German and refuses to hide it. If you are a Fiennes fan, “The Choral” will be released on the same day as “28 Years Later: The Bone Temple” (2025), thus inaugurating Happy Ralph Fiennes Week to those who celebrate it and avid followers who watch both movies will not be able to stop comparing the similarities and differences between his characters. Fiennes is more restrained to permit everyone a moment in the spotlight, but the audience may get a sense that the rest of the cast did not have to act when he spoke. It was not a heavy lift for them to seem awe struck at every word that he utters. He has always been one of the great actors, but his own excellence lends credibility to Dr. Guthrie being a renowned artist. The characters with the best voices have singers (Tia Jordan Radix-Callixte and Hugo Brady) performing the vocals, which includes Dr. Guthrie (Donald Stephenson) so at least Fiennes did not hoard all the talent.

Dr. Guthrie sees art as the place that transcends society’s ills and seeks to make the chorale into a place welcoming of all, a respite from the war and literally a sanctuary for his pianist, Robert Horner (Robert Emms), who is eager to sacrifice his life as a conscientious objector when the government drafts him. Guthrie serves as a man who sees the tragedy on all sides and does not permit the audience to get carried away with patriotism and rejoice over the other side’s death. Also, his rewarding of merit and welcoming of all societies makes him more of a ministering figure than any of the Anglican ministers who appear. “The Choral” skewers the provincial thinking of the area: anti-Catholicism, homophobic, jingoistic, xenophobic, but not racism, which does not exist. Mary and her mother (Cecilia Noble in a scene stealing single scene) are Black but are seamlessly integrated into the society with all of Mary’s problems stemming from her volunteer work. If anything, the movie course corrects so hard that Mary becomes the belle of the ball. While it is nice to get a reprieve from racism, is it whitewashing or aspirational utopian thinking?

The writers, Alan Bennett and Stephen Beresford, manage the difficult feat of not having a villain in sight. With Ellis complaining about the conditions at the mill, Duxbury could become the bad guy. He manages to be sympathetic because of the effect that the war had on his family and Allam’s ability to imbue him with genuine emotion. The real enemy is the senseless waste of young life because of war. Director Nicholas Hytner opens with a scene that could be mistaken for the Western Front.

The war is never far from the onscreen action even in the lighter moments, which makes the spectre of war so much more devastating when it disrupts the bucolic peace of this town. A back-to-back railroad station scene with a train going out and coming in is like getting doused with cold water. During the recruiting montage, the war comes to mind again. There is no way to forget it thus making the audience relate to the townsfolk’s plight and making the reality of war unforgettable.

Even though “The Choral” explains how they will stage and produce Edward Elgar’s “The Dream of Gerontius,” the performance is still incredibly moving when it is time to see the result of all their hard work. Hytner manages to keep songs dynamic when he shows different people in a variety of locations going about quotidian, simple joys while rehearsing, and the editor Tariq Anwar makes this sequence seem like a grounded musical explaining why it would be realistic for the entire town to sing outside of rehearsal. It sounds great. Dr. Guthrie reimagines the piece to reflect the times: “Art does come out of art.” Choreographer Tom English’s contribution is the devastating cherry on top.

“The Choral” will resonate with Anglophiles, classical music lovers and the oldsters, but it should be a little nothing movie that should not hit as hard as it does, but it happens to be released at a time where it feels as if the world is once again on the verge of another war. It does not feel like watching the past, but the future.

Digression Alert: Bennett and Hytner frequently collaborate: “The Madness of King George,” which Fiennes was also in, “The History Boys,” “The Lady in the Van,” “A Question of Attribution,” a twelve episode TV series, “Talking Heads,” filmed theater plays, “National Theatre Live: The Habit of Art,” “National Theatre Live: People,” “National Theatre Live: Allelujah!” Americans may remember Hytner best with his iteration of “The Crucible” (1996). In addition, Hytner has done more stage collaborations with Fiennes, which includes the memorable 1995 rendition of “Hamlet,” which was never filmed but is notable for coinciding with Fiennes began to split with his first wife, the magnificent Alex Kingston, and “National Theater Live: Straight Line Crazy” (2022), which was recorded, and now I need to see it. In the latter, Fiennes plays the Robert Moses. What!?!