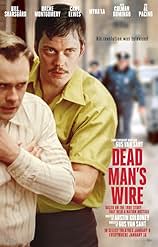

“Dead Man’s Wire” (2025) is Gus Van Sant’s latest film, which adapts the documentary “Dead Man’s Line: The Tony Kiritsis Story” (2018). On Tuesday, February 8, 1977, Tony Kiritsis kidnapped Richard Hall and held a shotgun to his head with a wire tied to the trigger and Hall’s neck. The hostage crisis lasted for sixty-three hours, roughly three days. In his feature debut, writer Austin Kolodney imagines what that time was like for the men at the center of the storm with Bill Skarsgård playing Kiritsis and Dacre Montgomery playing Hall. The casting is the most flattering glow up in cinematic history, and the race bending casting makes Indianapolis seem more multicultural and textured than it actually was.

There is not a person alive who doubts that Skarsgård is a good actor. Give him some scenery to chew, there will be no scenery left. “Dead Man’s Wire” may be the only movie that hurts itself when it shows a clip of actual footage of the real-life Kiritsis. Van Sant wants his audience to like Kiritsis. The real-life Kiritsis was swarthy, short and a ranter. Skarsgård’s Kiritsis is one of the three and gets a few amusing quips in. Kolodney definitely makes him less annoying.

Taste matters. Kiritsis’ unadulterated love of radio DJ Fred Temple (Colman Domingo), who plays amazing music, humanizes him and makes him relatable to everyone else, especially the movie goers. Who does not love Domingo? Fred’s voice closes the movie and feels like the narrator in spirit. The radio station is populated with a multicultural group that Benetton would tackle for an impromptu photo shoot. One guy, James (Vinh Nguyen) even smokes pot. If Kiritsis likes them, it makes him seem more countercultural. When Temple willingly works with the police, it also has the effect of vindicating their methods and choices. Fred Temple is a fictional substitute for the real-life Fred Heckman, who was compared to Walter Cronkite and was a journalist complete with horn rimmed glasses. In real-life, Temple and other journalists got a lot of criticism for obeying the police officer’s orders and potentially exposing their viewers to the possibility of his head blown up.

There is a Seventies cool aesthetic whereas the actual aesthetic of that era was way more homogenous, square and male. “Dead Man’s Wire” also is a story about a scrappy news reporter, Linda Page (Myha’la), trying to get more substantial assignments, and she gets her big break with ingenuity and cleverness. The actual onscreen talent was mostly male, all white except for Boston’s own Hank Phillipi (no Ryan then). There were Black media figures who played important roles, but could they report on such coverage? If so, then why did not the documentarians use them? If not, then why were they not allowed access? Van Sant incorporates actual footage that was also included in the documentary, and on a first watch, it is almost impossible to distinguish between fact and fiction, but after watching “Dead Man’s Line,” it is obvious. Van Sant has good taste for picking NBC News’ Mike Jackson clips.

The costume and wardrobe department makes the cops look cooler than they did at the time. Cary Elwes is completely unrecognizable as Michael Grable. The real-life Grable was wearing a sweater that Big Bird would feel comfortable in. Meanwhile Elwes looks as if he is auditioning for a remake of “Serpico” (1973) and sports a turtleneck and leather jacket. Van Sant makes the cops seem as if they are trying to do something and seem less clueless than they represented themselves to be in the documentary.

The real standout is Montgomery, who may depict Hall as more emotional than the real-life man appeared on television, especially considering the circumstances. He humanizes an unfortunately overlooked character, and his understated, mostly silent performance shows how wounding it must have been to hear everyone cater to Kiritsis while he was the one in too tight cuffs with a gun pointed to his head. Kiritsis suffers in comparison to Hall whenever Montgomery is onscreen. No one will walk away scoffing at Hall as a poor little rich boy. His desperation on the last day in Kiritsis’ apartment is visceral, and the constant barrage of humiliation is agonizing to watch. He grounds “Dead Man’s Wire” in real stakes in a way that does not happen in the documentary’s archival footage told from the point of view of journalists and law enforcement. It is Van Sant’s greatest accomplishment. His strangest achievement is making a film with an unusual villain.

Van Sant really tries to put his thumb on the scale and frame Kiritsis as an everyman who expresses the anger of the people, but somewhere along the line, it transforms into daddy issues. Normally, I watch a movie and write the review immediately afterwards. When I realize that it is based on an accessible documentary, I watch the documentary then write reviews for both. My reaction to “Dead Man’s Wire” was unusual. I enjoyed it, but was left with more questions than answers, and on the top of the list, did Tony have a point or was he just a jerk who cared more about his own profit than human life? The man of the people veneer covered a fame whore who wanted a pay day. He was losing his business, not his home, a valid grievance, but not one worthy of such extremes. There is a point when Kiritsis gets everything that he asked for, and it is obvious that he does not want it to end, but Van Sant does not frame him as the villain. In the final onscreen moment between Hall and Kiritsis, it appears as if they swapped places, and Kiritsis is a trickster who always wins, an insouciant anti-hero. So who is the villain? Hall’s daddy, M. L. Hall (Al Pacino).

Pacino really hams it up with a servant constantly trying to serve him with mixed results considering his fastidious habits. When asked to choose between business and his son, M.L.’s response is cold, and his pride in his son’s stoicism is emphasized. He is bad because he is rich and a father who prioritizes masculine norms. Kiritsis almost feels bad for Hall.

Did M. L. play a big role in extending his son’s captivity? The documentary never mentions him as a target and made it seem as if Richard was the real target. I’m so curious that I bought Dick Hall’s book, “Kiritsis and Me: Enduring 63 Hours at Gunpoint” (2017). Pacino and Kenneth Branagh need an intervention. Pacino sports a Southern accent, which is pretty bad, but amusing and seals his status as bona fide villain. The real M. L. appears to be from Indiana so the creative choice could be an eccentric allowance but further supports the villain theory. To be fair, a lot of the accents are puzzling, including Skarsgård. Are all cops supposed to be from NYC? On second watch, after watching the documentary and having a Kiritsis overdose, M. L. gets framed as the only one who refuses to give Kiritsis what he wants and seems to be the only one who pegs him correctly. Yes, he is a villain, but even with the ridiculous accent, Pacino makes Kolodney’s words take on a double meaning and almost feel cathartic because someone finally called a madman on his bullshit.

During the first watch, Kiritsis’ actual grievance seemed unintelligible or almost as if Van Sant was deliberately cutting it to get away from the possibility that the eat the rich rhetoric would sound like anything other than a madman’s ramblings. I’m not the only critic who thought so at the Boston screening. On second watch, after watching the documentary, I noticed that his argument appeared several times in different characters’ dialogue. So why does it seem so initially elusive? In part, Kiritsis is his own enemy and conveying an argument in an overstimulating environment with elevated emotions. If Kiritsis is interesting, it is because in the present day, a resurgence of violent reprisals for the face of business deals is on the uptick. Kiritsis has an audience almost half a century later, but not if his argument is clearly laid out, and it seems less righteous once understood. Van Sant needs an underdog, not a madman.

More importantly, Van Sant actually reduces the number of brothers who appear on screen. Only Jimmie makes the cut, but George Urgo, Kiritsis’ half-brother ,who gave water to Hall and Kiritsis during the last press conference, gets swapped out for a plainclothes law enforcement official. Jimmie was actually more soft-spoken, not a hot head like his famous brother, and George seemed almost servile and overly subservient. There is no mention of Kiritsis’ sister, Effie Georgia Kiritsis, Kiritsis’ first hostage. This creative omission makes Kiritsis seem less like a reprobate abuser with a potentially high recidivism rate. When he says, I’m not crazy, and the final scene makes him seem more like a leading man than a kidnapper, Van Sant is cultivating a more palatable figure who could be a folk hero.

While “Dead Man’s Wire” may be a well-intentioned alternate history that imagines a more inclusive, cohesive world, it erases endemic problems such as Kiritsis, a victim turned abuser, constantly getting to socialize with law enforcement and receiving little to no punishment for his actions. It does not question the journalists’ ethics and rehabilitates it through race bending. Van Sant should be praised for finally giving a voice to Hall, but he also buys the script that Kiritsis cast himself in as an underdog voice of the people sick of not being able to get ahead. It is a “Falling Down” (1993) for the twenty-first century, but do we really need more stories of rage from entitled men who feel owed and aggrieved and spend more time being violent than earning a reward? There are more emotions than anger, and it is unfortunate that the sharp edges of this story are further smoothed out for widespread corruption and sold as revolution, a trend that aligns with adoration for “One Battle After Another” (2025).