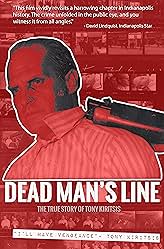

“Dead Man’s Line: The Tony Kiritsis Story” (2018) is a documentary about an Indianapolis hostage crisis that started on Tuesday, February 8, 1977, then lasted for sixty-three hours, roughly three days. Tony Kiritsis kidnapped Richard Hall and held a shotgun to Hall’s head with a wire tied to the trigger and Hall’s neck. Kiritsis called the police at the beginning of this crime, so cops and reporters covered every moment of this crisis. Indiana-based codirectors and cowriters Alan Berry and Mark Enochs create the definitive comprehensive story from the point of view of law enforcement, the legal system and journalists. It ends on a reflective note about the ethics for journalists and lawyers with no definitive answers. Gus Van Sant adapted this documentary for a complementary, scripted feature, “Dead Man’s Wire” (2025) told predominantly from Kiritsis and Hall’s perspective.

“Dead Man’s Line: The Tony Kiritsis Story” is Berry and Enochs’ second film together and their last traditional feature-length documentary to date. Usually, Berry directs and Enochs writes. Since then, they have stuck to short documentaries usually focused on music artists such as Neil Peart, Steve Vai, Van Halen and Black Sabbath. They focus on the latter for four movies! One of their movies focus on the making of John Boorman’s “Point Black” (1967). Their interest in Kiritsis was probably more about location, location, location than true crime and a desire to preserve local history, but they do better than most people who really geek out on the genre.

True crime devotees will probably devour it in one gulp. It is one of the highest quality true crime documentaries because there is only probably a few seconds of B-roll evocative smoke and mirrors. The film mostly consists of archived news broadcasts, montages of black and white photographs, newspaper clips and color photographs, and exclusive interviews with many of the people involved in the crisis. If you are not into true crime and are not into legacy broadcast news’ coverage of crimes, you may find yourself wondering if the lemon is worth the squeeze, and it probably is not for you. While the crime is sensational for having so many people indulge a perp’s hunger for fame and a voracious desire to air his grievances, it may be the very thing that repulses you. It is like holding yourself hostage because it is so accurate in the way that it depicts the unfolding of the crisis. For Hall, the real torture was probably having to listen to Kiritsis without any breaks.

Though a documentary is not required to interrogate and analyze an incident, it is frustrating that no one questions why Kiritsis knew so many law enforcement officials, was such a well-known volatile figure and yet never was stopped. The questions about law enforcement’s efficacy are limited to one unanswered question around the hour mark. Kiritsis received so much press coverage because law enforcement instructed television studios and radio journalists to cover the story and gave them access. Often both the journalists and law enforcement officials appear to argue Kiritsis’ grievances better than he did.

If you watch “Dead Man’s Wire” (2025), you are going to be frustrated that you never get to hear a clear version of why Kiritsis is so sore at a mortgage company. If the crime is interesting, it is because in the present day, a resurgence of violent reprisals for the face of business deals is on the uptick. Kiritsis has an audience almost half a century later. “Dead Man’s Line: The Tony Kiritsis Story” seems to suggest that Kiritsis got a mortgage on some land and was developing it, but when the bank got wind of it, they swooped in and took the deal for themselves. It is not nice, but hardly the 2008 financial crisis. The talking heads in the documentary seem torn regarding validating his grievance. Nile Stanton, one of Kiritsis’ defense attorneys, thought his client did not have a valid claim. Indiana University School of Law Professor Tom Schornhorst did not dismiss it out of turn. While the enforceability of the immunity agreement is poured over repeatedly, no one seems interested in the admission of guilt (under extreme duress) of the Meridian Mortgage Company. NBC News’ Mike Jackson, one of the reporters on the scene of the crisis, does the most effective job of understanding and conveying Kiritsis’ grievance. There is still room for other filmmakers to explore this subject and see if there is some systemic, foul business practice that needs to be stopped or just collateral business. With all due respect to Kiritsis’ hopes and dreams, would you want to do business with him? No conspiracy may be necessary.

Effie Georgia Kiritsis, his older sister and eldest among his siblings, probably would not again. She died in 1987. “Dead Man’s Line: The Tony Kiritsis Story” references a few times how he allegedly pulled the same stunt against his sister then the rest of the family financially rewarded him, which is actually how he got the money to get the mortgaged land, and refused to press charges. When this documentary was released, which was not that long ago, the concept of men escalating violence as predictable if you gauge the perp’s past with women existed but perhaps was not widely known. Again, Berry and Enochs’ film is more interested in capturing a moment in time, not deriving lessons from this story that can be applicable elsewhere. Even though family members readily participated on screen during the hostage crisis and one brother gives an exclusive interview, it is interesting that neither Effie, nor Hall, got to talk in the public eye. The press and law enforcement lack any curiosity about them. Even the profiler, Special Agent Patrick Mullaney, does not reference it as relevant information in the aired footage. Hall chose not to tell his story until after Kiritsis died, but Effie’s story is nonexistent.

The brothers orbit and defer to Tony. The family paid money to Tony so he could release his sister. Did they come together to help Effie heal? What were holidays like? Usually, the eldest sibling becomes parentified. There is markedly little analysis of the family though everyone believed that the patriarch was abusive. It is interesting how sympathy is directed towards Kiritsis’ situation, but not the only girl in the family, who was also the victim of an abusive family dynamic, which then had a ripple effect on a city, a state and a nation when the incident interrupted a national broadcast. A toxic family is only a microcosm of a toxic society that constantly caters to its most dangerous members. “Dead Man’s Line: The Tony Kiritsis Story” does an effective job of showing the national impact with the opening credits which provides context with a highlight reel of the key events of 1977, which includes John Wayne schilling for a financial product and becomes a full circle moment when his award speech gets interrupted for Kiritsis’ last press conference.

“Dead Man’s Line: The Tony Kiritsis Story” and “Dead Man’s Wire” offer the most complete existing story about the hostage crisis to date, but the actual story is not innately compelling unless you find the subject matter interesting. Hindsight is apparently not 20/20, and the only lessons learned are devoted to some closing credits about the effect that the spectacle had on criminal legislation. It is no “September 5” (2025), but maybe the unofficial inspiration for “Falling Down” (1993).