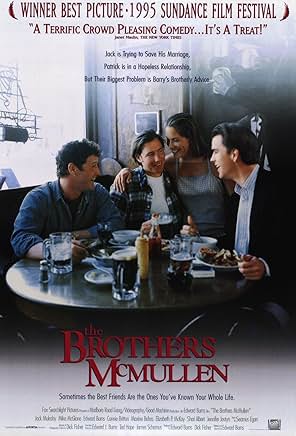

Set five years after their abusive, alcoholic father died, three adult brothers end up living together, but are afraid of taking the next big step in life out of fear of becoming like him or their mother and settling for the wrong person. “The Brothers McMullen” (1995) asks whether these brothers will avoid self-sabotaging, find true love and become happy. Despite their very best efforts, they somehow land on their feet. This beloved indie classic jumpstarted a lot of careers in film, including writer, director and actor Ed Burns and actors Connie Britton, Michael McGlone, Shari Albert, Maxine Bahns, Catherine Bolz, Peter Johansen, and Elizabeth McKay. While the movie is a beloved favorite for many, and it deserves a certain margin of error for being a first film and realistically evoking city life, it does not age as well as some of Burns’ other movies in terms of momentum, plot and character development.

I watched “The Brothers McMullen” to prepare for “The Family McMullen” (2025), the sequel that was unavailable to critics before release. It was probably a mistake to start the day watching “The Fitzgerald Family Christmas” (2012) before diving into Burns’ first film. Maybe none of his films will live up to that Christmas classic. It is a first film, but I went in with too high expectations instead of grace.

Without belaboring the trauma of their upbringing from watching their mother be in a loveless, horrific marriage and being the punching bag of a grown man, it is always the unspoken elephant in the room. In a vacuum, these three men are not great. In context, they are killing it. The eldest brother, Jack (Jack Mulcahy), a gym teacher, is married to the family favorite, Molly (Britton), the English teacher. He is happy until she starts talking about kids then is tempted at the idea of cheating. Finbar, Barry (Burns), a writer, is a hobosexual allergic to commitment ad a boatload of potential until he meets Audrey (Bahns), a woman who keeps rejecting him and changing the reasons why to keep him on the hook.

In a race to the bottom, Patrick (McGlone) loses and thus wins as the least horrible brother. He at least has the excuse of being the baby, freshly out of college and torn between accepting an easy path with Susan (Shari Albert), which would lead to a job and a Manhattan apartment, or his idea of a soulmate or his one true love, Leslie (Jennifer Jostyn), who is his opposite. Compared to his brothers, he has a sense of morality in terms of how he should treat other people even if he has not managed to find a way to apply it daily. Because he admits to being a bit dim, his lapses seem less about character and more about stumbling through the world with a vague idea of how he should act whereas Jack gets irritable with others for his shortcomings, and Barry is the least insightful person for a writer.

McGlone has been Burns unofficial brother for awhile, and it makes sense because his performances stand out even with Burns in the room, which speaks well of Burns’ lack of vanity to give the best parts to McGlone. Maybe McGlone makes them the best parts. Watching a young McGlone is like watching Philip Seymour Hoffman except with his accent, he cannot be a chameleon though he makes a wonderful character actor and is believable as the unofficial, unordained family priest, but instead of a confessional, a bathroom is where he counsels his fraternal parishioners in a brilliant, hilarious and serious as a heart attack scene between him and Jack. When he guesses the identity of the other woman, he ends up being the most self-aware, perspicacious brother. It is not entirely a coincidence when he finds his way around Easter Sunday.

Burns was not at the point where he got an ear for how women talk, and all the women are falling all over themselves to get to the brothers, which may be Burns lived experience because he is happily married to supermodel Christy Turlington, is undeniably talented and has a name associated with quality and success. The women are predictable except for Ann (McKay), one of Barry’s former dates. Considering the way that Burns introduces Molly, her storyline is resolved too rapidly and smoothly.

If anyone outside of New York or younger than some of the references watch “The Brothers McMullen,” it may leave them baffled or like unearthing a time capsule. References to Amy Fisher and Joey Buttafuoco and an impression of Archie Bunker saying a slur do not age well with the benefit of hindsight. At the time, those exchanges were cutting edge comedy. Graded on a curve, it could be worse. There is a blink and miss it shot of a phone booth and the Twin Towers, which is poignant. One cordless phone is the size of a character’s head.

As a filmmaker, Burns plays around with a couple of narrative tricks, which do not entirely work in terms of telling the story smoothly. He lets the audience hear the characters’ thoughts, but there is no rhythm to it. Occasionally when a character talks about the past, Burns depicts the scene, and the transition is not the smoothest. Sometimes there is not enough connective tissue between edited scenes with a character in bed then suddenly at a kitchen table talking to someone entirely different. It is an abrupt transition, so it takes longer to get into the subsequent scene for instance when Molly leaves a room after talking to Jack then is at a kitchen table, it takes awhile to see who she is talking to. It is Barry, but the subconscious expectation is that it will be Jack. There is a better transition soon thereafter between Molly washing dishes in the sink to Ann.

An underexplored thread of “The Brothers McMullen” is the lure of California. Barry’s career is on the upswing, and he may be able to make movies, but the reality of his humble origins and financial reality burst the bubble of his image. Leslie invites Patrick to go to California with her. New Yorkers care about real estate, and Barry and Patrick keep passing up opportunities to settle and live in Manhattan, retreat to the comfort of the familiar in Long Island and think of California as the promised land of opportunity. It is an interesting contrast with their Irish mother (Bolz) who repatriates to Ireland for true love. California becomes a way of escaping the gravitational pull of their past rooted in their childhood home and their father’s plot of land at the cemetery.

Burns’ feature debut is just not for me. Its target audience is probably cis heterosexual men who related to the character’s adult coming of age dilemmas and did not find it monotonous. While I found value in “The Brothers McMullen,” especially the ripple effect that it had on film and television and the way that it single handedly made it better, it is not the kind of movie that I would want to watch more than once.