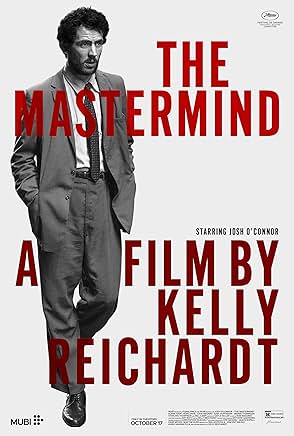

In 1972, Florian “Al” Monday, originally from Providence, a college art major dropout and an alum of Walpole State Prison, masterminded a robbery of three paintings (a Gauguin, a Picasso and a Rembrandt) from the Worcester Art Museum and worked with three Worcester natives (William G. Carlson, Stephen A. Thoren and David M. Aquafresca) whom he had schemed with before. This true crime tale inspired Kelly Reichardt’s latest film “The Mastermind” (2025) about James Blaine Mooney (Josh O’Connor), a family man with a secret vice, who steals four Arthur Dove paintings from the (fictional) Framingham Museum of Art. His life gradually falls apart. How will he get caught? Reichardt’s anti-heist movie is an artsy fartsy, autumnal delight except race bending casting of one of the thieves spoiled the fun because it leaned into stereotypes.

O’Connor is the main draw of “The Mastermind.” He is often the best part of any movie. He just inhabits roles, fits any era and makes the most routine activity intriguing. The dialogue is sparse in this movie. The protagonist spends a lot of time silently sizing up his options. He uses his family for cover, resources and clout. His taciturn wife, Terri (Alana Haim on the right side of the law in this movie and earlier appeared in “One Battle After Another”) and two sons, the bespectacled Tommy (Jasper Thompson) and chatty Carl (Sterling Thompson), are blissfully unaware that they are always visiting the museum because daddy is working. They often visit his vaguely disapproving dad, Bill (Bill Camp), and mother, Sarah (Hope Davis). It is a while before the moviegoer finds out that this older couple are his parents and not his in-laws. It is not until the police investigation that you find out his dad’s profession. He leads with thinking about himself, not his wife and kids.

One co-conspirator, Larry Duffy (Cole Doman), the car man, sees that trait in James, and self-absorbed James does not predict accurately that Larry is spooked and will jump ship because he is so self-absorbed and impressed with his brilliance that he stopped observing when it suited him. Guy Hickey (Eli Gelb) thinks of James as a friend. Another team member, a Roxbury native, Ronnie Gibson (Javion Allen), further complicates the plan. It is only one of many things that go wrong, and Reichardt sets up the tension well.

Visually, “The Mastermind” is gorgeous. Autumn is the best season. While watching the film, it reminded me of Kogonada’s “Columbus” (2017), and the museum scenes were shot at the same location, the Cleo Rogers Memorial Library in Indiana. Many had a problem with the deliberate pacing, and if you are expecting “Ocean’s Eleven” (2001), literally readjust to the opposite, and if you are still interested, give it a shot. Reichardt occasionally keeps the camera away from the action which adds suspense. When she chooses to keep the camera outside and stay on the car, it leaves the viewer asking questions: are they coming, will they both get away, what happened to the guard? A lot of it remains a mystery and is not necessary, but it is why it is an anti-heist, not only because of what goes wrong, but how she does not care about the actual logistics of the crime. In the reverse, she prefers a lot of long, still shots and gradually things pop up that further the people’s story, not the action. When the kids are suddenly in the back seat of one of the many cars, it is natural to wonder how long they have been there and what do they know? If James is irredeemable, it is the way that he exposes his family to harm.

“The Mastermind” is telling a story about one disaffected man during a turbulent political era of anti-war protests, disillusionment, and class divide except this man is seemingly uninterested in these issues except how they can benefit him. James cares about how he spends his time. One drive home reveals a possible motive: resentment of his dad and enjoying getting something over on him. Maybe he just likes not answering to anyone even though he has skills and options. Gaby Hoffmann plays a friend, Maude, who makes another guess that sounds close to the mark. It is a great cast, and after seeing “Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere” (2025), it is nice for her to get a meatier role. There are no real answers, and it is fine. Reichardt’s work is fun because she does not spell anything out and leaves a little mystery to her characters. The film shows James leveraging the hippie, draft dodging world for his own personal gain, not as part of a bigger cause or because it is truly who he is. He is still happy to keep a paw in his family’s pocket.

The racial politics of that era such as bussing and integration are not explicitly addressed though it was an issue at the time. Technically it did not have to be, but it feels like it is. For the fun of it, Ronnie takes a protestor’s sign from a bunch of women before jumping in the car. He is the wild card. He disobeys orders, enjoys brandishing his gun and threatens little girls. Ronnie is Black. With my respectability politics pearls firmly on, what is the reason for making a Roxbury resident and a Black man into the most violent of the team when the original team appeared to be all white? If I’m wrong, please let me know. It just felt like laying it on thick. He was not just a Black guy who lived in Worcester, but he had to be from Roxbury.

Black actors have a right to be able to take human roles, and human beings can be criminals who do horrible things. On the other hand, when a Black character is a wrongdoer that overlaps with racial stereotypes, it takes me out of the movie, and it did in “The Mastermind.” As a long time Massachusetts resident, before researching, I knew that a Roxbury Black man would not be a part of this team. A sleepy guard, sure. A guy in the bar talking about his criminal transgression then enlisting to get out of it, absolutely. These are flawed Black characters who seem like credible people depending on the timing and place. While this movie is fictional and does not have to adhere to reality, when it does not, it is for a reason and is a choice. What does race bending this character tell us about the time, place and people? The effect is not the same as intention, and for this viewer, the effect hurt my ability to focus on this otherwise superb, understated subversion of a genre.

If you fancy yourself a film lover, Reichardt’s films are required viewing, and if she is not your cup of tea, it is fine, but you must accept that your tastes may be a bit conventional. The ending is a complete payoff to attentive viewers. While “The Mastermind” is a clever tale of privilege and prejudice, it also (hopefully) unintentionally reinforced some mainstream media images instead of consistently creating complex character studies of three-dimensional people who are inscrutable but make some sort of sense.