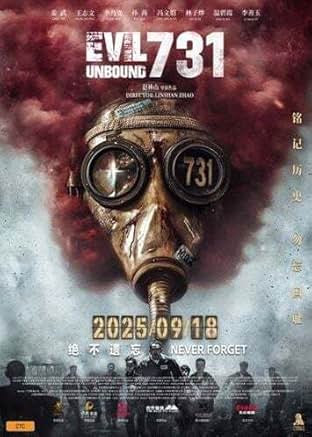

“731” or “Evil Unbound” follows a man (Wu Jiang) who could be a normal Chinese man turned traitor called Yongzhang Wang or a legendary anti-Japanese resistance fighter named Ziyang Wang. When he gets sent to Pingfang Station in Harbin, fellow prisoners hope that he is the latter so they can escape before their Japanese captors kill them in sadistic experiments. If Chinese writer and director Linshan Zhao had not made this film, it would be dismissed as trivializing horrific war crimes for lurid, prurient reasons. As it stands, by trying to embrace certain film techniques and genres, it is a severely flawed film that tries too hard to find a way to make a uplifting film about a difficult topic without being unremitting and joyless.

“731” follows the plight of a group of prisoners in the cavernous camp styled to look antiseptic like a medical facility but hides a house of horrors. The cell’s surfaces are tiled as if they are in a spa. It gets disguised as the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, a pretense that drops soon after the end of the first act. The Japanese tell the prisoners that their health is being monitored, and they will release them once “cured.” The camp commander, Ishil Shiro, who is based on a historical figure, oversees the experiments and often dresses in traditional garb. The uniformed head of recruits, Kayo Imamura (Feng Wenjuan), is a twisted woman who enjoys her job too much. Two new Japanese recruits, Ichizawa and Yoshikawa, who works in the “imaging” or film unit, are a bit out of place as goofballs who would rather enjoy the camp’s amenities and are not as into torturing the prisoners as everyone else though still unfeeling.

Wang is an opportunist and survivor who is always looking for a way to get the most of out of a situation. A family group of performers, a father, daughter and young son, Minglian Sun (Lin Ziye), get separated from each other, and Sun ends up in Wang’s cell along with Boxuan Gu (Li Naiwen), a weeping husband and father-to be who is inconsolable over being forcibly separated from his pregnant wife and doctor, Suxian Lin (Sun Qian), who is also there. They are expecting their child to arrive on August 15, 1945. They are roomed with a long-time inmate Cunshan Du (Wang Zhiwen), who has tamed a rat, Mao Mao, to communicate with the cell next door. Russian prisoners from Khabarovsk punctuate scenes probably in honor of the fact that the USSR held members of Unit 731 on trial in that region in 1949 while the US protected Ishii and other key members to benefit from their war crimes, which actually did not produce much scientifically valuable information.

As a story, “731” often verges on incomprehensible because Zhao chooses style over substance. If you are watching it for the first time, a lot of it does not make sense, and no one really wants to see a movie like this more than once to unpack what is happening. Zhao is less concerned with realistically conveying daily life in the camp as much as the genius, plucky spirit of the prisoners despite the monstrous, psychotic behavior of their captors. It sometimes feels sacrilegious for certain moments to be played for laughs, especially in the scene where Gu is correctly crying over what has happened to him.

Zhao’s opening sequence is an expressionistic blend of hyper realism with bold colors and archival footage or at least times when he shoots the events in black and white to symbolize what is occurring on the front. Flashbacks are also shot in black and white. The first time that the camp is onscreen, it looks like he is deliberately pulling a Leni Riefenstahl with the unfurling of the Japanese flag over the fortress’ high walls then lights shine through the red circle to bathe the entire scene in red. It is gorgeous and the constant formation and style of the enemy is deliberately marrying the Japanese Imperial Forces with the Nazis. Other moments seem unintelligible, surreal and random. For example, a procession of traditionally garbed people suddenly appear in the hall. It is like watching a very stylish, antiseptic season of “American Horror Story.” A lot of the prisoners get tortured on crosses, which is apparently accurate. Maybe a double feature with “Silence” (2016) is warranted.

“731” understandably understates the horrors of Unit 731 and prefers to emphasize “The Shawshank Redemption” storyline with Wang using clues from his roommate to draw a map of the facility. Zhao depicts the camp like a well-oiled, orderly and clean machine. It is not dirty, and though the smell of the place is discussed, it looks positively gleaming. There were rampant rape and torture done off the books so that seems to be a fantasy that probably did not reflect reality. There are a couple of scenes showing red vials of blood hung like decorations and tags in the ceiling that makes it seem celebratory and festive, not a laboratory. Ishil has several children who talk over the loudspeakers, and they can easily be mistaken as his children, but later Shiro kills one of the girls’ white pet rat, and they are upset, but not scared of her. It would take an eagle-eyed viewer to figure out that these kids were probably born and raised at the camps, but unaware of their actual parentage.

When characters write in other languages, it is not translated for English speakers. The timing and at least the English translation of intertitles offering information seems to brief, a common problem in Chinese films. They usually get clustered together and are too small to read without pausing, which ruins the momentum of the movie. Also, if the information cannot be derived from watching the film, then it ruins the narrative’s trajectory without enlightening the viewer. “731” suffers from this pacing problem and does not know how to end because there are no high notes in this story. It wraps up with anonymous butchery and serial killer vibes then a lot of intertitles explaining what happened with the camp, the commander and stating that the Japanese surrendered on August 15, 1945. While the credits roll, there is archival footage of a former camp employee, Masakuni Kurumizawa, discussing the atrocities at the camp. A documentary would be preferable tothis film.

“731” verges on bad taste as exploitive cinema. It feels more like a horror movie than a somber mirroring of what is normally expected in World War II films about the Holocaust and concentration camps though it also borrows imagery from that genre as well. On the other hand, considering that Chinese people are making the film, and Chinese people were the ones harmed in these experiments, to put it in terms of common vernacular, “Go off, queen.” You do you.

Zhao should let other people do the writing and stick to visuals. If he ever decided to make a horror film, that movie would be stunning despite the repulsive gore, but his techniques applied to a historical horror does not sit well and is a mistake. Zhao knows how to keep his audience as disoriented as the prisoners, but a story like this needs to be comprehended so it can be passed down with lessons learned. It made “Site” (2025) seem tasteful in comparison.