“After the Hunt” (2025) is Luca Guadagnino’s latest film. Starting in 2019, ranging from the lofty heights of Yale University’s campus to Connecticut’s waterfront, Alma (Julia Roberts) and Hank Gibson (Andrew Garfield) are vying for the same tenure position, but Alma’s therapist husband, Frederik (Michael Stughlbarg), sees Hank at the front of the line of suitors who use academic posturing as cover for their desire to get closer to his wife. Second in line is Alma’s prize pupil, Maggie Price (Ayo Edebiri). Maggie and Hank engage in a war to win Alma to their side claiming the other to be a monster. Such posturing repulses Alma from any allegiance. Alma is only on her own side, and even that stance is tenuous. Will Alma ever stop self-sabotaging herself and let herself be happy?

If the above paragraph sounds different than the movie described in the trailers, it is because it gets to the heart of the story, not its political veneer which is shabbier, coy and cheap subconscious posturing which may tell a story best left unsaid for actor turned first time writer Nora Garrett. Guadagnino is usually messier than this pseudo heady affair, but “After the Hunt” is sexless, buttoned up and reflexively uptight that even drugs and alcohol never loosen this threesome up. The trailer tells a story about sexual harassment, cancel culture, and the feminist generational divide. The movie goes further into clumsy grasping at race and class. Let’s circle back around to all of that in the spoilers, but for now, let’s give the pros.

Roberts as an ice queen is fun to watch. Roberts knows how to deliver reams of dialogue without rolling her eyes at how ridiculous most of it is. The hair is perfect. The wardrobe is crisp. No curves. All lines. The suggestion of a body, but the proof is hidden in oversized blazers. Alma is a fun character as she goes from fabulous location to fabulous location with ample couches, beds and oversized stuffed chairs to sink into while she holds court about her latest insights about life, philosophy and others as if they were precious jewels. It is an idea of what it is like to be a professor. Her life feels more like Park Avenue than Connecticut with her capacious marital apartment, a kitchen the size of most apartments, and on and on and on. If “After the Hunt” fails, it never explains her desire to achieve that particular kind of career success.

Garfield as Hank is at his sluttiest (compliment) showing all his man cleavage with four to five buttons open, all hands with anyone in reach whom he is attracted to and always a tease leaning in for a kiss that lands too close to the mouth to be considered innocent, but too far to be inappropriate. It is a great performance until it is time to rage and behave exactly how anyone would not if they were accused of sexually harassing a student. It is as if he has no one in his life except Alma.

Same for Maggie. Edebiri has a thankless job as the Christ figure who must get denigrated for the entire movie and act hella shady while still pulling some level of empathy out of the audience. In real life, Roberts probably jumped to her defense because the whole movie basically calls her character stupid, wealthy (derogatory), needy and too sensitive. Edebiri is not a chameleon kind of character and feels as if she is playing a version of herself in any role, but Maggie may be her most complex role to date since she needs to have a mysterious air to keep the suspense going. She dresses almost identically to Frederik in the party scene, the only time where all the relevant players occupy the same space.

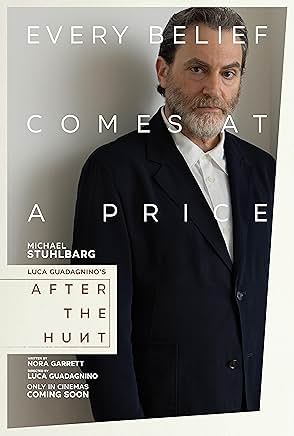

Frederik is the only character who seems to like himself and enjoy his own company, but he does not have much choice in the matter. He treats Alma like a queen, is extremely tolerant of the company that she keeps, enjoys playing music loudly and swans around the house with a flourish. Frederik could have been a thankless character, and if his sexual orientation was different, their marriage would be the ideal lavender marriage. If Stuhlbarg appears in a Guadagnino film, best believe that he is the voice of moral authority and will explain the entire point of “After the Hunt” in the denouement.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

“After the Hunt” is about how Alma never forgave herself for correctly accusing her first love of being a pedophile, so it colors how she responds to Maggie’s allegations. Garrett puts Alma in the center of the controversy as if her reaction matters the most, and she is the central character wronged, which the dialogue notes. Either it is a subconscious or deliberate skewering of a real phenomenon of centering certain women’s comfort and/or the filmmakers are playing it straight and really believe in their story, but the execution makes it unclear though the following tilt towards the prior. When Hank initially flirts with Maggie, Roberts plays Alma with a micro expression of a grimace, not bemusement. For God’s sakes, by fainting, Alma gets out of students confronting her.

Every character, including Maggie, is an unreliable narrator. Just because everyone agrees that Maggie is a bad student does not mean that she is a bad student. It is a common microaggression that Black women face regardless of the quality of their scholarship. Maybe she is not good in Alma’s class because she has a crush on her and/or wants to impress her as a substitute mother figure, so she is imitating her. She likely has other classes so if she really was plagiarizing, she would get in trouble, and that allegation never goes beyond the inner sanctum. Frederik asks Maggie why she is interested in her dissertation topic, and she is clearly going through the motions. Is immediately jumping to mediocre or dumb fair or does her Blackness mean they unfairly expect excellence from her because she is a woman and Black whereas others get to be dull.

Their opinion is undermined when Alma lasers in on Kate (Thaddea Graham), another woman of color, to rip her to shreds. Alma pays dust to the guys in her class, August (Will Price) and Marcus (Ariyan Kassam?), and either quiets them or rewards their silence. It is the pet to threat principle. If women of color obey Alma and follow in her footsteps, she rewards them, but when they do not, she eviscerates them as if they broke an unspoken deal. They are supposed to be grateful and obedient.

If Maggie is truly guilty of something in their eyes, it is for not feeling grateful for an opportunity. Everyone references Maggie’s wealth, but Guadagnino only shows Alma’s wealth. It is as if wealth is supposed to cancel out the disadvantage of her race. Don’t tell Oprah who gets turned away from stores or Serena Williams who gets the same maternal health care as other Black women despite her wealth and fame. What Maggie is guilty of: invading Alma’s privacy, “single white female”-ing her and being a bad girlfriend to her trans nonbinary partner, Alex (the criminally underutilized Lio Mehiel).

If I was aggravated, it was after the slap. I kind of wished that “After the Hunt” was dishier. What is the point of Maggie being affluent and owning the school if Alma is not going to get Maggie’s parents to give her everything that she wants after Maggie slapped and pulled Julia’s hair with witnesses?!? If we’re going full on “Dynasty” with Alexis and Crystal, the twenty first century edition, complete with a denouement debrief between the two, it needs to commit to the bit.

The sexual harassment storyline is coy. Rape is not mentioned almost until the end of “After the Hunt,” and Hank uses the word. At the eleventh hour, Hank gets rapey with Alma, which retroactively validates Maggie’s account, but earlier when he asks about Maggie at Tandoor, the Indian diner, it felt like fishing. Some people mentioned that because Maggie had the article, she had a motive to lie to get closer to Alma, but she does not translate the article until later in the film. It is not unusual for rape victims to shower, not get a rape kit, etc.

If “After the Hunt” is problematic, it paints 2019 as the old days of DEI and #MeToo. Five years later, CNN broadcasts Meta ending DEI and fact checking omitting that one fact checker is allegedly a white supremacist organization. Alma is in power, and the bad good days are back. The final shot of a $20 bill, which has Andrew Jackson’s face, is another veiled reference to Presidon’t. If Alma is the hero, then this film is officially more subtle than a jeans commercial or a certain pop star’s Nazi merch. If Alma is the villain or anti-hero, then the movie is a cautionary tale of what happens when a person gets in power who only cares about herself, refuses to take sides and has no understanding of the concept of objective truth over ambition. Depiction does not mean cosigning, and the winter atmosphere suggests that the victory of the ice queen bodes poorly for the health of the campus that exists to simply serve her with no vibrant student body or anyone in sight.