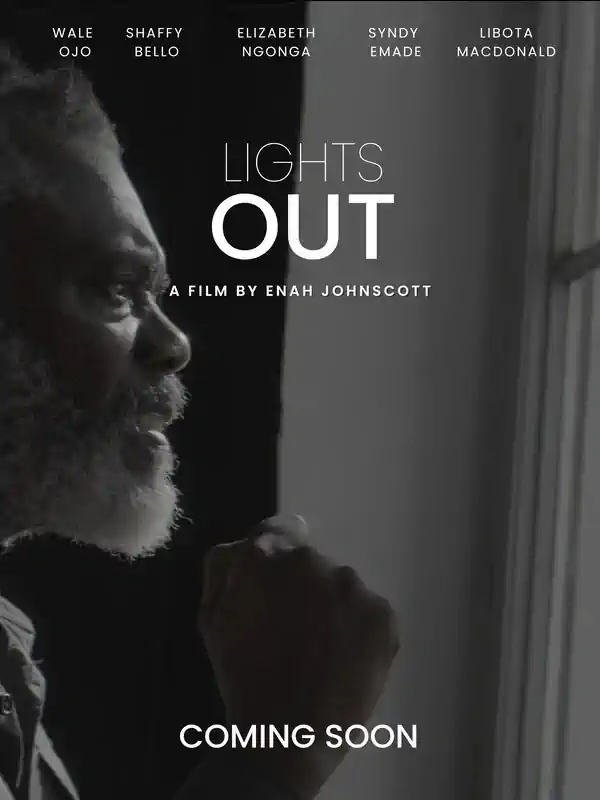

On a rainy day, a group of people shove a man, Lucas (Wale Ojo), into a car driving on a traffic jammed city street. When he wakes up to a lush, peaceful and sunny place, he eyes everyone around him suspiciously, but they seem to only treat him with care. Is he a victim of kidnapping or something else? “Lights Out” (2025) borrows a page from “Shutter Island” (2010) while chronicling daily life at Anone Dementia Care Foundation, a facility where the staff and funds are dwindling. Will they find his family before they close their doors?

“Lights Out” is divided between telling Lucas’ story and the survival of the facility and could have blended the stories more organically. Instead, it felt as if it stopped telling one story to resume telling the other. Ojo is pitch perfect as a man in denial about his health and options. Lucas and all the patients are oblivious to the fact that they endanger themselves when they lash out at their caretakers. When Lucas finds some peace when a new patient, Monica (Ngongang Elizabeth), arrives, it is predictable how their stories are interconnected. Monica functions as a pressure valve that eases the tension as the only one who can interact with Lucas without Lucas becoming hostile. Side note: in the US, usually the roommate situation is not coed, and considering that Monica thinks that she is a child, their emerging relationship is unintentionally alarming though Lucas is blameless considering his diminished capacity. In a vacuum, it is a sweet late-stage romance. Do not try this at home unless you want lawsuits and the police involved.

Monica’s initial onscreen introduction is as shocking and disorienting for the audience as the character. It highlights the high stakes that these residents face if they get turned out the door. As Black Americans, the impression of the diaspora is that there are some universal morals that survived long after leaving or being taken from our original homeland. One is taking care of our elders. It was a shock to discover that people may see people suffering from dementia as a threat rising to the level of witches and wizards. A subsequent prose drop as part of a worker’s fundraising speech explains the earlier scene. A prose dump means that it felt like the information should have been depicted instead of shown. A prose drop explains what we are witnessing and confirming it. The distinction is entirely subjective.

The eleventh-hour reveal of Lucas’ identity and the origin of his Christmas trauma felt like a sucker punch without enough time devoted to unpacking the memory revelation, which appears in the forms of flashbacks told from a new character’s point of view. Dropping a bombshell just as the film is wrapping up opens the door to so many other questions that the story needed to cut more to make room and expand on the ending. It either meant that there is a sexual assault story or an issue that would rock the foundation of Lucas’ relationships with his loved ones, especially Beverly (Elung Brenda), his daughter. Coincidentally, this movie is being released after “One Battle After Another” (2025) so most audiences would not need an origin story for the Christmas trauma.

The facility story line was challenging to watch because the stakes are so high. Hearing the motivations of the facility founders, Dr. Henry (Libota McDonald) and Maria (Shaffy Bello), was heavy-handed prose drops that pulled zero punches. Because of Lucas’ suspicion, it is hard to shake that feeling even after the mistake is dispelled. Each resident gets a snapshot of attention to reveal their struggle though none get as much coverage as Lucas. None of these stories involve heartwarming pablum of residents and loved ones just lovingly spending time together as in “The Thursday Murder Club” (2025). All the visits are harrowing to watch as the parents do not remember the child and accuse them of vile acts or forgetting them entirely while the adult children take it on the chin and keep coming back for more. Yup. “Lights Out” excels at balancing, not dismissing, the children’s pain without losing sympathy for the parents, which can be the reason that people end up not caring for people suffering from brain disorders.

The facility’s status is left to the imagination, but it is far from thriving. The best scenes are when Maria, who is put together and delivers inspirational speeches, just gets stone faced looks in response and keeps failing. If “Lights Out” was an American movie, she would be rewarded, the facility would be safe, the workers thrilled to be there, and the patients would be well mannered. Instead, there is real ambiguity regarding how the place will function and what will happen to the residents. Jofi (Irene Nangi), a perceptive worker, similarly does not get rewarded for her insight regarding how to soothe all the residents when they begin to get riled up.

When “Lights Out’ depicts an adult caring for their parents at home, it is the only time that punches are pulled. It is likely because the priority is finally providing the key to all the story’s mysteries, but once dementia patients are no longer mobile and are losing their ability to be verbal, it is almost impossible for a single person to care for someone that incapacitated. Just talking an immobile person to the bathroom and lifting them takes someone skilled without hurting themselves. Even though these images are peaceful, it is still unsettling because even in the best circumstances, dementia is a Sartre type hell.

Director Enah Johnscott and cinematographer Takong Delvis Mezzo execute writer Buh Melvin’s story perfectly because they depict Lucas’ subjective perspective of his surroundings, which did make everyone seem suspicious. Pay attention to Beri (Syndy Emade) and how she dresses depending on how Lucas sees her. One balcony scene genuinely felt as if it would result in death. The deliberate glitches like a worn VHS tape or corrupted digital stream conveyed the issues with the residents’ memory. A brief camera shot showing a framed poster-sized photograph then editing with a shot of Dr. Henry reflects his guilt over his inability to provide the standard of care that he wants to deliver. The location choice is brilliant.

“Lights Out” is probably the most realistic movie about living and working at a dementia care facility while also being nicer than its US counterpart since their goal is not making money but protecting people at their most vulnerable. While the story could have benefited from revision and should have omitted the eleventh hour melodramatic sensationalism, it is the rare movie that shows how it is impossible to win in the battle against Alzheimer’s and dementia. Also people who find Christmas triggering may enjoy the film.

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

S

Justice for Monica. Beverly (Elung Brenda) needed to snatch up the work colleague because he raped Monica after she got drunk at the party. Then her husband torments her and causes irreversible brain damage thinking that she cheated.